Once again, I find myself indebted to the fine folks at the publisher Armchair Fiction, for alerting me about a book whose existence I probably would never have learned of without their assistance; hardly the first time that this has happened. The novel in question in this instance bears the curious title Thus Far, which was initially released in 1925 by both the British publisher Hodder & Stoughton and the American publisher D. Appleton & Co., and then sank into virtual oblivion for a full 96 years, until Armchair chose to revive it for a new generation just a few months back. Thus Far is the product of English author J.C. (John Collis) Snaith, who’d been born in Nottingham in 1876 and was thus pushing 50 at the time of this book’s release. Almost as well known as a cricket player as for his writing, Snaith would eventually come out with some three dozen novels before his death in 1936, at age 60, although Thus Far would be one of his few efforts in the realm of sci-fi. An elegantly written and literate work that touches on a favorite trope of early sci-fi, that of the superman, Snaith’s novel also mixes in futuristic science, mind control and telepathy into one fascinating stew.

And yet, for at least the first half of its length, the book comes off more like a murder mystery than an exercise in Radium Age science fiction. The events in it are narrated by a 42-year-old bachelor named Robert Fremantle, a biologist of rising fame who lives in the heart of London. To his great surprise and wonder, he one day receives an urgent letter from his old mentor Graham Delaforce, beseeching him to come at once to his isolated abode in Hampshire. Although the two had not seen one another in over a decade, Fremantle still harbors some affection for the older man, with whom he had journeyed throughout Africa some 20 years before, and whom today was widely regarded as a brilliant but eccentric chemist, biologist and naturalist. But when Fremantle duly arrives at Delaforce’s home, The Hermitage, he learns that not only are the butler and Delaforce’s niece, Sybil, unprepared for his visit, but that the great man himself has gone missing. The police have been called in, and soon enough, the scientist’s body is discovered in a woodland lake, his throat torn out and his head battered in! Fremantle stays over to assist the devastated Sybil, and before long they are paid a visit by Robert’s old Cambridge acquaintance, John Lumsden, a man of such manifold abilities that he is only summoned by Scotland Yard for the most difficult of cases.

And this one promises to be a doozy, what with Sybil acting increasingly frightened and withdrawn, and with signs that Delaforce’s laboratory building had recently been ransacked at night, its lock picked by someone using only unnaturally dexterous fingers! Eventually, it comes to light that Delaforce had placed a son of his in a home for the mentally disturbed some 10 years earlier. And so, tipped off by the home’s suspicious superintendent, Fremantle goes to pay this personage, named Orr Galvin, a visit, and is shocked to discover the hypnotic power, the evil aura, and the mocking intensity of feeling that emanate from this peculiar man … not to mention Galvin’s freakishly tapered fingers! And then matters grow even worse, when Galvin escapes from this home for the mentally challenged, and a series of Jack the Ripper-style murders commences in the heart of London…

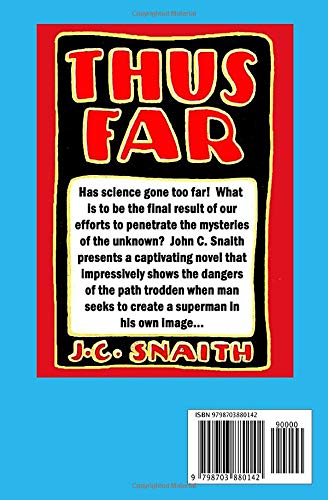

As I say, the book strikes the reader initially as more of a murder thriller than a sci-fi work, and thus the book’s actual intent is given away in what I can only regard as spoilerish fashion on the covers of both the original 1925 hardcover as well as this Armchair edition. That 1925 release’s front cover, which is here reproduced as this Armchair volume’s back cover, revealed that the novel “…shows the dangers of the path trodden when man seeks to create a superman in his own image…” Meanwhile, Armchair’s front cover more bombastically declares “A Walking, Talking Mass Of Genetically Engineered Flesh … And Dangerous!” Perhaps now you’ll have a better idea of what this book is all about! As for the novel’s unusual title, the words “thus far” should not be taken in the sense of “up till this point in time,” but more like “up till this point of advancement.” The words are biblical in origin … from Job 38:11, to be exact, which tells us “Thus far you may come and no farther.” It is a line that Sybil cites as a favorite of her uncle’s, who took it as a warning about prying too deeply into God’s domain. As he believed, “There are powers in the universe far mightier than he and if he rouses their antagonism he will be overthrown” … words that prove unfortunately prophetic, as far as the great scientist is concerned.

As I say, the book strikes the reader initially as more of a murder thriller than a sci-fi work, and thus the book’s actual intent is given away in what I can only regard as spoilerish fashion on the covers of both the original 1925 hardcover as well as this Armchair edition. That 1925 release’s front cover, which is here reproduced as this Armchair volume’s back cover, revealed that the novel “…shows the dangers of the path trodden when man seeks to create a superman in his own image…” Meanwhile, Armchair’s front cover more bombastically declares “A Walking, Talking Mass Of Genetically Engineered Flesh … And Dangerous!” Perhaps now you’ll have a better idea of what this book is all about! As for the novel’s unusual title, the words “thus far” should not be taken in the sense of “up till this point in time,” but more like “up till this point of advancement.” The words are biblical in origin … from Job 38:11, to be exact, which tells us “Thus far you may come and no farther.” It is a line that Sybil cites as a favorite of her uncle’s, who took it as a warning about prying too deeply into God’s domain. As he believed, “There are powers in the universe far mightier than he and if he rouses their antagonism he will be overthrown” … words that prove unfortunately prophetic, as far as the great scientist is concerned.

Thus Far does not feature any scenes of memorable action or derring-do, but Snaith nevertheless does supply the reader with any number of well-interspersed, suspenseful set pieces. Among them: Fremantle noticing a light emanating from Delaforce’s lab building in the dead of night, and going to investigate; Fremantle and Lumsden laying a trap for the perpetrator inside that lab soon afterward; Fremantle’s initial meeting with Orr Galvin, inside that mental facility; and Fremantle’s final confrontation with Galvin, as part of a police operation to apprehend the fiend. Snaith also supplies us with a trio of fascinating and well-drawn leading characters. Fremantle, our narrator, is realistically shown as being petrified with fright during practically every crucial moment, continually getting drawn into the dire events against his will. Lumsden is a character very much in the Sherlock Holmes mode, but one who does not seem to need the stimulus of cocaine injections to remain supersharp of mind. And as for Galvin, he initially arouses the reader’s loathing, with his patronizing, amoral and murderous ways, but by the book’s conclusion, the author makes us see him more as an object of pity. No, we never come to exactly like him, but at least we do learn to feel for his sorry plight.

Snaith’s style here, as I mentioned, is at once both literate and elegant, and indeed, some may feel that this particular book is often a tad overwritten. His range of literary and historical reference is intimidatingly wide, and characters are apt to quote such figures as poets William Ernest Henley, John Keats, Alfred Tennyson and John Milton at a moment’s notice, or make casual offhand references to composer Edward Elgar and novelists Honore de Balzac and Oliver Goldsmith. And Fremantle and Dr. Helyar, the superintendent of that mental asylum, discuss Plato’s “cosmotheorus” and an Inogensoutus (whatever that is … Google couldn’t help me here) as if they’re the most natural topics for conversation in the world! This is a very British novel, and will surely pose some trouble for most 21st century American readers. British slang words abound (I was most curious as to what Lumsden’s “blowing of a grampus” was about!), as well as distinctly British references (the Hellfire Club, “Gloomy Dean” William Inge, the Cock Lane ghost). As I say, Thus Far is not an “easy book,” and will surely require some research on the part of most readers for a full appreciation. But I have always found that such minor efforts are more than compensated by the fuller and richer understanding gained thereby. Fortunately, Snaith, during the course of his novel, demonstrates a near-impeccable command of the authorial art, only slipping up on a single occasion: On page 55, he tells us that Delaforce’s laboratory door was reached by climbing up six stone steps; on page 75, that number changes to eight. But that is the single instance of loss of control in the author’s complex and otherwise meticulously detailed story.

Now, as for this Armchair edition, it is a very pleasing one, sporting none of the numerous typos that have plagued so many of the publisher’s previous releases. And then there is that cover, which depicts a 1940s kind of dame, almost a Joan Bennett type of brunette, being menaced (?) by a caressing hand. What does this striking portrait have to do with the book in question? Well, to be honest, the answer is: Absolutely nothing (say it again!). Similar to the previous Armchair novel that I read, Garrett P. Serviss’ The Second Deluge (1911), this portrait of a lovely lady with a menacing mitt before her face relates back to nada in the story whatsoever. Go figure. Still, Armchair is surely to be thanked for resurrecting this lost wonder from almost a century back for today’s modern audience. Snaith, as I mentioned, does not seem to have ventured very often into the sci-fi realm, although his 1913 novel An Affair of State is said to deal with the England of the near future, and his 1921 novel The Council of Seven supposedly evinces some fantastic content. But based on my personal experience with J.C. Snaith, uh, thus far, I would most definitely be interested in checking out those other titles one day…

Oh, Sandy, the lengths you will go to deliver a pun…

😁😄😁😄😁😄