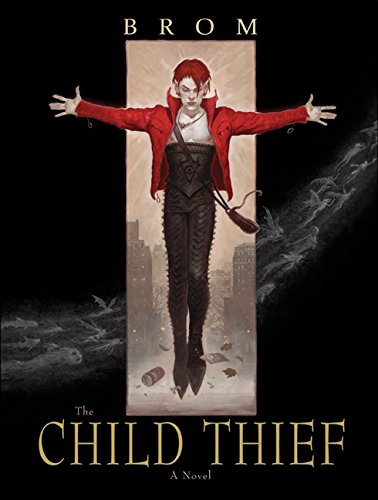

![]() The Child Thief by Gerald Brom

The Child Thief by Gerald Brom

The Child Thief is one in a long line of novels, graphic novels, films, and cartoons concerned with giving “gritty retellings” of J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan, or to give that book its original name and set it apart from the play, Peter and Wendy. The phenomenon of taking an innocent old classic and muddying it up is and has been fairly widespread, but Peter and Wendy is particularly popular because it was arguably gritty enough from the start, and authors like Gerald Brom consider themselves to be not so much twisting the story as advertising it in its original form.

Yes, Peter and Wendy hails from those bygone days of yore at the turn of the twentieth century when men were men and even young boys were considered well on their way to being men. The children’s stories of this period were not precisely cautious with violence and even could be rather blasé about the matter. The trope of villains falling into convenient bodies of water in order that our pint-sized heroes didn’t have to bloody their hands was just not particularly fashionable at the time, particularly in boys’ stories. Perhaps this is due to a more warlike culture by comparison, or perhaps first person shooters simply hadn’t made their glorious appearance to eat up the desensitization market yet; but whatever the case, it remains a fact that books like Treasure Island, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, and Peter and Wendy were somewhat bloodier than Disney films might lead the modern audience to expect. Specifically, Peter Pan in Barrie’s original could be quite the little savage at times, kidnapping children for purely selfish reasons, countenancing murder at the drop of a hat, quickly forgetting about casualties in the Lost Boy ranks, and even — it’s hinted — knocking a few of the lads off himself if they showed distressing signs of growing up or disobeying his orders. In one memorable scene, Peter prepared to execute Tootles for accidentally shooting Wendy, while Tootles advised him to “strike true”.

Brom takes these elements and runs with them. What he creates is darker and more horrific, but also curiously less thematically disturbing, than the original. His version of the story contains many themes the original did not — zombies, elves, minotaurs, and Celtic deities, for a handful — most of which are very dark. His tone is extremely cold as well, emphasizing time and again the brutality of both the Neverland and the mortal world. The opening chapters are extremely bleak and intentionally disturbing, meant to shock the reader to some extent. Yet at the same time, in a strange way, much of this is done almost as Peter Pan apologetics. Brom strives to characterize Peter in a way that Barrie did not. Barrie’s Peter was charming and eerie at once, but always distant. He was for the most part kept at arm’s length from the reader, with Wendy doing the lion’s share of the work as protagonist. Even when events occurred from his perspective, the narrator kept a firm two steps back from Peter, letting this structure emphasize the alien qualities of the character. It’s been long known in literature that the easiest way to construct a legend is never to tell the reader too much. Brom, by contrast, gives us everything. He constructs a Peter Pan who is intimate, understandable, and ultimately relatable. It’s an ambitious move, and it mostly pays off, I’m happy to say. This new Peter isn’t quite as charismatic as the old, but he’s an interesting character in his own right. The price for this new character, however, is that Brom must explain why Peter is killing his own soldiers and stealing children in a way that doesn’t make the character a complete villain. It takes a while and some narration that may strike newcomers to the Peter Pan literature as overlong or unneeded, but ultimately he manages it.

Indeed, I have a lot of admiration for the time Brom has spent constructing his Pan for the modern age. The characters are interesting, the mythology is a little cluttered but fairly rich nonetheless; and while the prose is somewhat rough at points, it’s forgivable in a relatively new author (particularly considering the number of veteran writers who aren’t at this level). Aside from Peter, the story has an interesting supporting cast and there are some genuinely pulse-pounding scenes. The pacing is good, and I was never really tempted to put the novel down.

I suppose it’s conspicuous, however, that I haven’t mentioned the main plot yet. Let’s get it over with: I found the plot the weakest part of the novel. Brom does well setting up his world and characterizing his protagonists. He gets all his ducks into a fairly decent row, but the course he leads them on never quite feels like the most sensible route to take. The story feels needlessly complicated at times, and there are a number of subplots that are present solely to get the story moving toward Brom’s finale, with much too little thought given to concealing the fact. If The Child Thief were a puppet show, it would have a large hairy hand dipping onto the stage every so often to adjust some bit of scenery, with the puppeteer not even bothering to don a black glove.

The Ulfred plot in particular feels jarring and ill-considered. No special reason is given for Ulfred to go mad other than some silliness involving his friends liking Peter more. To get where Brom needs to go, however, Ulfred must turn nuttier than a Snickers bar, and posthaste. So Ulfred, obliging fellow that he is, sportingly hops right off the deep end with no questions asked and no convincing motivation other than his magnanimous desire to sacrifice himself for the good of the suspense. He turns from nonsensical apathy and jealousy to nonsensical homicidal psychopathy in the blink of an eye, so quickly one can practically hear gears grinding.

Ulfred is the most glaring example, but there’s a lot of rather lazy plotting. It holds up, for the most part, but it asks the reader to swallow rather too many “I guess that could happen”s and tosses out too few likelihoods to compensate.

However, I must admit that I enjoyed The Child Thief. It’s resolutely dark, grim, and violent right to and through the end, so it’s certainly not a charming fairy tale. On the other hand, few fairy tales were charming in origin. To sum up, the book is rough. It’s very much the novel of a man who hasn’t tried anything of this magnitude before and is working out the kinks. That said, for those unbothered by the gritty atmosphere (or for old Barrie fans) this is a story that is entertaining despite its flaws, a decent read and a retelling that never feels as if its only goal is to ride the coattails of its predecessor. It’s an ambitious, bold run at Peter Pan, and here I’m with Fortune in favoring the bold.

COMMENT Was I hinting that? I wasn't aware of it. But now that you mention it.... 🤔

So it sounds like you're hinting Fox may have had three or so different incomplete stories that he stitched together,…

It's hardly a private conversation, Becky. You're welcome to add your 2 cents anytime!

If the state of the arts puzzles you, and you wonder why so many novels are "retellings" and formulaic rework,…

I picked my copy up last week and I can't wait to finish my current book and get started! I…