![]() Kingdom Come by Mark Waid and Alex Ross

Kingdom Come by Mark Waid and Alex Ross

To understand Kingdom Come, you have to understand a few things about superhero comics. Now, if you have any sort of interest in the genre at all, I’m sure that sentence opens up nightmarish recollections of previous rabbit-holes down which you’ve ventured to try to understand some seemingly simple question like “what is the history of Supergirl?” or “why are there so many different people named Captain Marvel?” The history of superheroes and their comics is weird, convoluted, and sometimes nigh-maddening. Look at Grant Morrison: he probably knows more about comic books than almost any other graphic novelist alive, and he’s been known to write in phrases like “nurseries where omni-anemones fed and grew to become quicksilver angels in a timeless AllNow.” Not that the man isn’t brilliant as all get out, but perhaps let’s just say comic books can move your mind to a funny place. I promise, though, that this lecture will be short and sweet and probably won’t destroy your sanity. Probably.

To understand Kingdom Come, you have to understand a few things about superhero comics. Now, if you have any sort of interest in the genre at all, I’m sure that sentence opens up nightmarish recollections of previous rabbit-holes down which you’ve ventured to try to understand some seemingly simple question like “what is the history of Supergirl?” or “why are there so many different people named Captain Marvel?” The history of superheroes and their comics is weird, convoluted, and sometimes nigh-maddening. Look at Grant Morrison: he probably knows more about comic books than almost any other graphic novelist alive, and he’s been known to write in phrases like “nurseries where omni-anemones fed and grew to become quicksilver angels in a timeless AllNow.” Not that the man isn’t brilliant as all get out, but perhaps let’s just say comic books can move your mind to a funny place. I promise, though, that this lecture will be short and sweet and probably won’t destroy your sanity. Probably.

Our tale begins in that period where comics stopped being children’s impulse buys in supermarkets and started becoming adult collectibles in specialized novelty shops. For reasons too complicated to go into just now, the average age of the comic book reader had dramatically spiked. This new audience wanted more mature storytelling and more complex themes (not least because a good number of them wanted validation in the opinion that comics were appropriate for their age group). The audience loved Frank Miller‘s The Dark Knight Returns, adored the aforementioned Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth, and when Alan Moore‘s superhero deconstruction Watchmen exposed the essential problem of carrying the notion too far (i.e. that superheroes carried past a certain point of realism largely cease to be superheroes), audiences largely ignored that part of the subtext and used Watchmen’s bleak tone as a guiding light (much to Moore’s later chagrin).

By the start the 90s, the boom of 80s reinvention was dying down into the medium’s Hot Topic-wearing, death-metal-playing adolescence. What had begun as an interesting experiment into maturity and depth quickly devolved in many cases into shameless pandering as one ostentatiously grimdark idea followed another. Green Lantern went crazy and murdered all his friends, Superman died and came back with a mullet, Batman was replaced by a murderous lunatic named after the angel of death, and Spawn became popular. Spawn.

That’s Spawn, seen here inexplicably rocking a fanged-skull codpiece. I say “inexplicably” only because it’s not nearly garish enough to match the rest of his wardrobe.

That’s Spawn, seen here inexplicably rocking a fanged-skull codpiece. I say “inexplicably” only because it’s not nearly garish enough to match the rest of his wardrobe.

By the mid-90s a backlash had begun to develop. Just like the schism in fans of superhero cinema today, there was a division at the time between fans who loved the darker material and others who believed things had gone too far and begun to pollute the essential nature of the superhero archetype. Two of the latter camp were named Mark Waid and Alex Ross.

This gets us, at long last, to Kingdom Come, which recasts the basic premise of The Dark Knight Returns as a Superman story in which the Man of Steel confronts the absurdities and ultra-violence of 90’s comics culture and shows it just how very unimpressed he is. Oh, it’s subtext, but only in the sense that Aslan being Jesus is subtext in the Narnia books. The creators really wanted to get their point across.

The plot goes something like this: Superman has retired from the heroic life following the revelation that the youth of today just don’t agree with his old-fashioned, folksy methods. They prefer cool, badass young bucks who are willing to kill and maim to accomplish their ends. With Superman’s departure, the world mostly ends up in the hands of a next generation of superheroes who proceed to royally mess things up. Heroes fight each other more than they fight villains, collateral damage is all over the place, and fighting for a cause seems to have been replaced by just… fighting. Sound familiar? See, that’s the interesting thing about Kingdom Come. In terms of comic books, it’s definitely a ways behind the times, but in terms of film, it’s still quite timely. Anyway, Superman is eventually convinced to return and set things right, beginning a sequence of events in which it becomes clear (at least according to the book) that truth and justice might be more timeless and mature than any of this grimdark 90’s childishness.

The plot goes something like this: Superman has retired from the heroic life following the revelation that the youth of today just don’t agree with his old-fashioned, folksy methods. They prefer cool, badass young bucks who are willing to kill and maim to accomplish their ends. With Superman’s departure, the world mostly ends up in the hands of a next generation of superheroes who proceed to royally mess things up. Heroes fight each other more than they fight villains, collateral damage is all over the place, and fighting for a cause seems to have been replaced by just… fighting. Sound familiar? See, that’s the interesting thing about Kingdom Come. In terms of comic books, it’s definitely a ways behind the times, but in terms of film, it’s still quite timely. Anyway, Superman is eventually convinced to return and set things right, beginning a sequence of events in which it becomes clear (at least according to the book) that truth and justice might be more timeless and mature than any of this grimdark 90’s childishness.

The first thing to say about this book is that it is gorgeous. That’s a necessity, because in fact the narrative does not make a very cohesive argument for Superman’s position. It gets as far as “these kids today are too reckless and violent,” but Superman’s alternative example doesn’t quite soar as it should. Like so many other Superman works, Kingdom Come struggles with the problem of Big Blue Boy Scout’s actual appeal and largely falls back on the customary position of lamenting that no one seems to think Superman’s cool anymore without giving a firm reason as to why anyone should. I mean, this is after all a version of Superman who abandons humanity for a couple decades because he’s not getting enough media love. Fortunately, Alex Ross’ art flies to the rescue. Ross is one of the few artists who can make paintings work in comic books, and he used models to give his work a sense of realism. That isn’t to say that the art is perfectly photorealistic, mind you, just enough so that there’s a disarming sense of tangibility about these figures. Under Ross’ gentle brush and carefully chosen palette, the face becomes someone you could meet… or more likely someone you could have met in some idealized past. The lighting in Kingdom Come is always sunny morning or late afternoon, evoking a vibe of Rockwellian Americana, and the coloring gives the feel of an old photograph from before the digital age.

In short, Ross has cracked the code for a pictorial representation of pure nostalgia. It ultimately doesn’t matter that the writing has no definitive answer for why we should support Superman. All we have to do is look at that art. When I first read this graphic novel, I had no idea who half of the characters were, but even so I found myself thinking “ahhh, that’s right. Those were the good old days. These were the true heroes.” It’s hard to overstate just how perfectly Ross fits this project. Without him, Kingdom Come simply could not work.

The writing doesn’t reach the same heights. That isn’t to say it isn’t fairly good, mind you. Waid and Ross both evidently had a hand in the words, so it’s hard to say which one of them one should credit, but it all evens out to a serviceable job. Unfortunately, though, it’s pretty obvious that this book was intended as a thunderous, operatic work of immense scale, and it doesn’t quite get there. While the dialogue is fine, the narration can sometimes seem a little forced and melodramatic, and there are several noteworthy occasions where concepts are simply stated that probably would have been more effective as implications. It feels an awful lot like they were trying to channel Neil Gaiman on Sandman or Alan Moore on Marvelman, but something doesn’t land with the oomph that it should.

Part of Waid and Ross’ issue, I think, is that while Kingdom Come is arguing against the self-consciously serious Dark Age works, the book itself teeters on the edge of becoming overwrought and humorless. Ross’ art is all grandiosity and aching devotion to a bygone glory, leaving little room for quirkiness or self-parody. Kingdom Come takes itself very seriously, and at certain points all the hand-wringing and schmaltz can seem almost as silly as the brooding, pretentious tropes it’s trying so hard to torpedo. On the other hand, there’s something disarmingly sweet and earnest about the narrative that in many ways comes the closest out of any element in the text to giving us a reason to love Superman, and the general plot is solid. There are some hiccups here and there, but I reiterate that it’s not bad writing by any means, just a little less moving than the creators were clearly hoping it would be.

Overall, this is a good graphic novel and a great piece of art. While it doesn’t necessarily achieve its immense ambitions, the work is nevertheless well worth reading and is particularly topical in the modern discussion on tone in superhero film. Kingdom Come does not necessarily make superheroes convincingly serious fare, but it does succeed in making them venerable and worthy of respect for what they are and have been, rather than for the more violent or realistic entities they could be adapted into. If this book doesn’t instill in you the desire to see a happy ending to the Batman vs Superman film, nothing will.

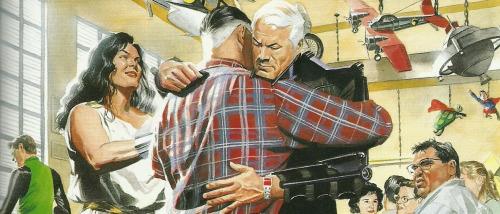

Look, I’ll prove it to you. Here’s a sweet-as-apple-pie image of an aging Supes and Batman hugging it out in a diner while a delighted Wonder Woman reflects that this is the most adorable thing she’s seen all day.

(meanwhile, that Frank Miller fan in the bottom right looks on in total disgust, wondering when Batman turned into such a sentimental old geezer. But hey, you’ll never please everyone).

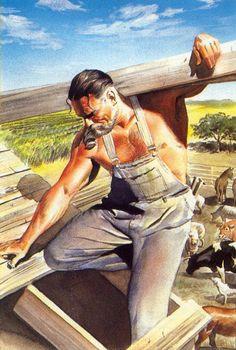

Tim, what a great review. And what stunning artwork! The image of Superman (?) working on the barn roof is absolutely beautiful, and carries a bit of Christ symbolism with the hand curled over the board.

Excellent, excellent review, Tim. I completely agree — the art outshines the writing on every page, but it’s still an enjoyable addition to my comics collection.

What a timely summary of the swinging pendulum of tone in the comic book world over the last few decades. And I’ve never heard of this comic and it’s attempt to fight against the darkness introduced by Frank Miller (intentionally) and Alan Moore (less so). I’d love to see the artwork even if the story doesn’t sound quite so enticing. I’ve always been more of a Batman than Superman fan, even before Frank Miller and Christopher Nolan, but I have yet to see the new movie either.