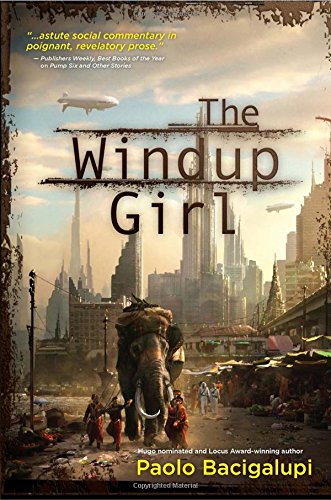

![]() The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi

My Body is Not My Own…

Having just finished Paolo Bacigalupi’s Hugo and Nebula award-winning novel, I’m left rather bereft at how to describe, let alone review, The Windup Girl. I am not a big reader of science-fiction or dystopian thrillers, which means that no obvious comparisons come to mind, and the setting and tone of the novel are so unique (to me at least) that they almost defy description.

Set in a future Thailand where genetically engineered “megodonts” (elephants) provide manual labor and “cheshires” (cats) prowl the streets, the world’s population struggles against a bevy of diseases brought on by all the genetic tampering that’s been going on. Oil has long since run out, Chinese refugees flood the cities, the seas are rising, and power now lies in the hands of “calorie companies.” These corrupt organizations can manufacture crops, though the “generippers” have designed the seeds to be infertile, thereby forcing the purchase of their products indefinitely. Corruption, blackmail and backstabbing are commonplace, and struggle for survival is very much a reality for all walks of life.

The titular character is a Windup Girl named Emiko, designed to be the perfect servant, trained never to disobey an order, and easily identified by her “stop-stutter” motion. Having been abandoned by her original owner and now peddled as a novelty sex-toy, Emiko is treated as a subhuman. In reality, she is railing against her engineering whilst dreaming of freeing herself from her life’s constraints. Yet despite being the book’s namesake, the novel contains an ensemble cast that is roughly centered on the doings of Anderson Lake, a company man who works undercover as a factory man whilst he combs Thailand markets for food that is thought to be extinct.

There’s also his secretary, a formerly wealthy Chinese businessman who has escaped massacres in his own country and is now an amoral survivalist, set on ripping off his boss, and Captain Jaidee, known as “the Tiger of Bangkok” who is incorruptible in his defense of his country, but who resorts to violent means to get what he wants. Lastly, there is Jaidee’s second-in-command, the stoic Kanya, who has a dark secret in her past that is completely at odds with her loyalty and respect for Jaidee.

No character is entirely sympathetic or completely vilified. Instead, everything is painted in a distinct shade of grey, from the calorie men who are out to make a profit by whatever means necessary (but who also strive to combat the threat of plagues that threaten mankind) to the environmental ministry who use violent measures against their own people to defend their country and its seed-farms. There is no main character, and so it is really the city of Bangkok that becomes the most important element in the novel. Bacigalupi writes in prose that manages to be both sparse and descriptive, and that brings his world to vivid life in all its heat, danger, cruelty, beauty and genetically modified wildlife.

For those interested in Bacigalupi’s version of Bangkok, he has already explored this dystopian world in his short-stories, notably “The Calorie Man” and “Yellow Card Man,” though familiarity with those works aren’t necessary to follow the story here. Rather, one of the most exciting things about the reading experience is the way in which you are thrown head-first into an unfamiliar world and left to sink or swim in it — much like the characters that populate it, you have to find a way of negotiating the chaos or you won’t last long.

I feel as though this review may not be adequate, simply because I don’t have enough experience in this particular genre to make an educated critique of the book. Maybe that’s a good thing though, as from a layman’s point of view, I can say that I was intrigued by The Windup Girl, was never bored, and didn’t stop reading until I reached the end. It’s imaginative, unpredictable, dark, and extremely well written.

~Rebecca Fisher

![]() Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Windup Girl won the 2010 Nebula Award. I understand why. This is a novel of Big Ideas, a bold move and an interesting premise. Bacigalupi’s reach exceeds his grasp, but a flawed, risky work of art often has more value than a success that played it safe.

Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Windup Girl won the 2010 Nebula Award. I understand why. This is a novel of Big Ideas, a bold move and an interesting premise. Bacigalupi’s reach exceeds his grasp, but a flawed, risky work of art often has more value than a success that played it safe.

In a vividly realized Bangkok of the future (100-150 years from now) Anderson Lake, an undercover “calorie man” who works for the mega-conglomerate AgriGen, schemes to get access to the rumored Thai seedbank, believed to hold genetic material of vegetables and fruits long extinct, which the Thai are cautiously reintroducing. AgriGen and one or two other companies have a monopoly on the world’s seeds and grains, and their seed-stock grows more and more susceptible to plagues and opportunistic viruses like blister rot. This bio-homogenization has led to starvation around the world. The calorie companies are in a constant race with the viruses, and constantly searching for new (old) material they can mutate and patent. Lake’s mission criss-crosses with the machinations of Hock Seng, an ethnic Chinese Malaysian refugee — a “yellow card” with precarious immigration status — and Jaidee Rojjanasukchai, a Thai folk hero who works for the Environment Ministry.

In this post-petroleum world, computers are powered by foot treadles and kink-spring technology creates mechanical batteries. Lake uses a kink-spring factory as his cover, and Hock Seng is the factory manager. Lake is on the trail of a new fruit he found in the market, and in the course of his search, he meets Emiko, the Japanese “windup girl,” a genetically engineered sex toy, programmed to be beautiful and submissive. Emiko is a vat-grown Geisha trying to be Pinocchio.

Despite the name of the book, the “windup girl” is not a very important character. She isn’t even much of a secondary character, and that’s a good thing. She was not a plausible person to me. Her alleged struggle between genetic programming and her desire for free will never rang true. Emiko is a toy to the characters around her who exploit her, and a tool to the author, who needs her to do one particular thing near the end of the book. Her apparent struggles, shown through the same interior monologue she repeats several times during the course of the book, are unconvincing.

This is a problem with the character, but the book’s structure adds to the problem. The first half of the book is slow, and the characters are passive. Things get put in place that are needed later, but they are disconnected from the actions of the protagonists. The only exception is Jaidee. Jaidee’s actions have consequences and resonance, and that may be why he is the most memorable character, and seems to be the most effective even when he fails.

In the first thirty pages of the book, Lake shoots a rampaging elephant-mastodon. This is a wild, breath-taking, suspenseful sequence. Then Lake does nothing much else for a very long while. He is supposed to be secretly looking for the origin of the mystery fruit. Instead, he hands them around like oranges. He goes to the bar where the Westerners — the farang — hang out and sips warm whiskey. Hock Seng engages in a lot of interesting activities that highlight his growing desperation and his hatred of the White Devils, but do not advance the plot.

The slack plot, so early in the book, when so many characters are being introduced, left me with too much time to think, to grow irritated with Emiko, who seems not tragic and noble but merely whiny. Despite her constant internal protestations that she would like to be “free,” the book slants her story in such a way that it is clear she does not want freedom, but Bacigalupi, for me, falls short of showing why she cannot even accept freedom when it does come to her.

These problems continue for more than half the book. Suddenly, on page 207, betrayals happen. Suddenly, the streets are alive and dangerous. Suddenly, a strong woman character emerges. Suddenly, fortunes are reversed, and reverse again, and things start to happen. People get shot. Things explode. The book lumbers off the runway and wobbles into flight.

The Windup Girl tends to read like three separate novellas that were broken into chunks and interleaved. The actions of our three main characters, all male, should create some tension and opposition for the others, and they don’t. Bacigalupi is primarily a short-story writer, with several stories written in this universe. There is enough good material here to reassure me that we will not see these kinds of structural problems in his later novels, and the world-building alone makes this a four-star book, even if the title character doesn’t work.

One warning: while a lot of the violence directed toward men is softened somewhat, seen in memory or after the fact, the writer subjects the windup girl herself to two brutal rapes that are described in detail. Plainly, Bacigalupi thinks he needs both of these scenes, which are nearly identical, in order to show us some development on Emiko’s part. For some people this will be very difficult to read.

The Windup Girl is a book worth reading for the world Bacigalupi has built and the story he tries to tell. It was a bold move and an interesting premise and despite the weakness of the structure and some of the characters, it mostly works.

So go read it. If you like war-games and military science fiction, you’ll probably like it even more than I did. Get your friends who don’t understand what all the fuss about climate change or genetically modified food is about to read it too. Then be prepared for a lively discussion that’s going to go on late into the night.

~Marion Deeds

![]() I thought The Windup Girl was excellent. A dark, intricate and gorgeously written environmental dystopia filled with fascinating characters. For a debut novel, it’s a stunning accomplishment. Beautiful cover illustration, too.

I thought The Windup Girl was excellent. A dark, intricate and gorgeously written environmental dystopia filled with fascinating characters. For a debut novel, it’s a stunning accomplishment. Beautiful cover illustration, too.

~Stefan Raets

The Windup Girl takes place in a alternate future Bangkok, Thailand. The world is dying due to a rash of genetic diseases that have decimated the world food supply. The only food available is via corporations who have created various disease-resistant food products. They sell to the populace for huge profits, except in one place: Thailand. Thailand has a real history of independence from foreign influences, and this still holds true in Paolo Bacigalupi’s dystopian future Bangkok. Somehow the people of Thailand have figured out a way to create their own disease-resistant foods. The corporations are determined to figure out how.

The Windup Girl takes place in a alternate future Bangkok, Thailand. The world is dying due to a rash of genetic diseases that have decimated the world food supply. The only food available is via corporations who have created various disease-resistant food products. They sell to the populace for huge profits, except in one place: Thailand. Thailand has a real history of independence from foreign influences, and this still holds true in Paolo Bacigalupi’s dystopian future Bangkok. Somehow the people of Thailand have figured out a way to create their own disease-resistant foods. The corporations are determined to figure out how.

The story follows several characters, such as Anderson Lake, an American “calorie man” sent by the corporations to figure out how the Thai are developing resistant foods; Emiko, the genetically created “windup girl” who has been abandoned by her former owner in a brothel; and Jai Dee and Kanya, environmental ministry officers with their own agenda in keeping Thailand safe from farang influences (Thai slang for “white foreigner”). There are many more essential characters, almost too many to keep track of. There is one thing all characters have in common: none are very likable. Emiko, the fragile genetically created prostitute, is probably the most endearing character in the story. All others are scheming selfish bastards, or at least incredibly dense and morally obtuse.

I found the story itself a bit hard to follow. Seemingly important events are only mentioned briefly, whereas seemingly unimportant events are given three or four pages of in-depth descriptions. I was listening to this via audio, and it was hard to stay focused. It might have been easier if I had been reading print. I also want to note that the anti-cooperation/eco-terrorism political theme is prevalent and may chafe some readers.

Paolo Bacigalupi is an extraordinarily talented writer, and he certainly did his research. I have read very few authors who understand the idiosyncrasies of Thai culture. Having spent a lot of time in Thailand and around Thai people (my wife is Thai), I was very pleased to see that Bacigalupi has taken great care in incorporating this research into the story, but in the end it wasn’t enough to keep me interested. I need to identify with at least one central character in order to stay focused on the story. That may be a fault in my tastes, but it proved to be the downfall in my ability to enjoy The Windup Girl.

Paolo Bacigalupi is an extraordinarily talented writer, and he certainly did his research. I have read very few authors who understand the idiosyncrasies of Thai culture. Having spent a lot of time in Thailand and around Thai people (my wife is Thai), I was very pleased to see that Bacigalupi has taken great care in incorporating this research into the story, but in the end it wasn’t enough to keep me interested. I need to identify with at least one central character in order to stay focused on the story. That may be a fault in my tastes, but it proved to be the downfall in my ability to enjoy The Windup Girl.

I had a difficult time writing this review. I gave it a DNF (Did Not Finish) not because it was bad, but because it simply wasn’t the book for me at the time I read it. I may someday finish the story, but I have too many other great reads ahead of me in the near future to struggle through it at this point. I listened to this on the audio release by Brilliance Audio. Once again Brilliance has unleashed a very high quality production. The book is read by Jonathan Davis, who was quite excellent and had the appropriate tone for the novel. There were some hard words to pronounce in English, and Mr. Davis did pretty well.

~Justin Blazier

Chapter one — really interesting. Chapter two — really interesting. Chapter three — hit the off button about five minutes in.

Chapter one — really interesting. Chapter two — really interesting. Chapter three — hit the off button about five minutes in.

Let me explain how that worked.

The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi is the story of a near future earth where food is controlled by calorie companies because all the naturally occurring food sources have been wiped out by plagues, and the new animals and plants are genetically engineered and patented. This massive restructuring of basic sustainability, combined with the disappearance of oil and the oceans rising globally and destroying coastal cities like New York, combine to create a world that is at once strangely foreign and completely natural. It feels like a steampunk novel, with a weird combination of advanced technology and manual labor creating a dystopia that feels all too possible.

Chapter one is told from the perspective of one of the calorie men, Anderson, who is sent to Thailand to discover how the Thai people are creating their own food in defiance of calorie company patents and contracts, and to discover how to exploit the new sources that Thailand is developing. He’s a harsh, uncaring man, aware that he is serving private interests over the public good and completely okay with that.

Chapter two is told from the perspective of his personal secretary, Hock Seng, a Chinese man who is a yellow card, a refugee from Malaysia where the Chinese have been persecuted and slaughtered by the Green Headbanders, radical Islamic fundamentalists. His secretary hates both Anderson and the Thai people equally and is intent on corporate espionage, trying to steal copyrighted information to earn enough money to reestablish his clan that has been exterminated.

And then we got to chapter three, where we meet the titular Windup Girl, Emiko. She is genetically engineered, raised in a crèche and trained from birth to be a servant and a sexual companion in Japan, where the technology is understood and admired. When she is cast off and sent to Thailand, where she is seen as potentially demonic, she is sold into sexual slavery. I hit the off button when she is raped on stage as a form of entertainment. The graphic brutality turned my stomach. While recognizing that sexual slavery is reaching epidemic levels throughout most of the world, I do not want to read about it for entertainment purposes.

This is a compelling story. The narrator of the Brilliance Audio production I listened to, Jonathan Davis, is mesmerizing, with the right amount of bitterness and languid pacing to reflect the oppressive heat and horrible life circumstances of the people in the story. While none of the characters are likable, they are complex and recognizable as real people. This is definitely an issue story — dealing with topics of environmental degradation, food security and international terrorism, but done so in a way that hadn’t seemed preachy so far. I just couldn’t deal with the sexual violence.

~Ruth Arnell

![]() Having swept the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards in 2010, this book should have been a slam-dunk for me. A dystopian near-future story set in Thailand, in a post-abundance world where genetic diseases have wiped out most staple food crops, rising ocean levels have flooded most coastal cities, and fossil fuels have been completely exhausted. Biotech ‘calorie’ companies hold the world hostage with ‘genehacked’ crops that are rendered sterile to ensure continual demand, but they are constantly battling to stay ahead of ever mutating plagues and diseases like blister rot that decimate crops and keep much of the globe near starvation. Due to the lack of oil, energy sources have been reduced to genetically-engineered ‘megadonts’ (giant elephants), kink springs (batteries that store energy that has been cranked manually), manual labor, etc.

Having swept the Hugo, Nebula, and Locus awards in 2010, this book should have been a slam-dunk for me. A dystopian near-future story set in Thailand, in a post-abundance world where genetic diseases have wiped out most staple food crops, rising ocean levels have flooded most coastal cities, and fossil fuels have been completely exhausted. Biotech ‘calorie’ companies hold the world hostage with ‘genehacked’ crops that are rendered sterile to ensure continual demand, but they are constantly battling to stay ahead of ever mutating plagues and diseases like blister rot that decimate crops and keep much of the globe near starvation. Due to the lack of oil, energy sources have been reduced to genetically-engineered ‘megadonts’ (giant elephants), kink springs (batteries that store energy that has been cranked manually), manual labor, etc.

This grim, steampunk near-future world is meticulously depicted by Bacigalupi. He’s clearly done his research on the culture, history, and sights/sounds/smells of Thailand. Behind the polite smiles and gentle demeanors lie more sinister undercurrents. Notably, Thailand continues its proud tradition of independence among the Asian nations. It has weathered all the numerous plagues, famines, wars, etc. that have swept the globe by maintaining strict border controls and more importantly a precious seed bank of disease-resistant crops, thus ensuring food security where other Asian nations have collapsed. This of course does not go over well with the calorie companies, who desperately want access to the seed bank for their own profit. Anderson Lake is a ‘calorie man’ for AgriGen, a cold and calculating economic spy sent to track down the seek bank. He uses a kink-spring factory as his cover. When he encounters a new variety of fruit in the markets, he knows he’s on the right track.

Then he meets Emiko, the ‘windup girl’ of the title. She is a New Person, an artificially grown human in a crèche and genetically modified to serve as a sexual toy for Japanese elites. Faced with an aging population and lack of laborers, the Japanese have engineered these ‘windups’ to serve various functions in society, from manual labor to military models. For some bizarre reason, Emiko’s movements are mechanical, stilted, and herky-jerky. Supposedly this design reflects the various ceremonial duties such as tea ceremony that Emiko’s kind are designed for, but that really didn’t make sense to me. There’s no reason to make artificial humans so imperfect. In any case, Emiko is a sexual plaything for the various unpleasant male characters in the book, and though she supposedly struggles against her genetic design and conditioning to be subservient, she mainly serves as a ‘deus ex machina’ for a key event later in the novel, and I found her character both unconvincing and somewhat offensive. There are plenty of stereotypes of subservient Asian women in popular culture, so I can see the rationale behind extrapolating this to a near-future SF context. Emiko strongly reminded me of Songmi~451 in David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, a ‘fabricant’ that serves real humans as a pliant slave in a dystopian future Korean state. However, Songmi becomes a messiah of sorts, while Emiko does not.

This recurrent theme of subservient Asian women really irritates me, but I need look no further than Japanese TV shows, anime, and manga to see the constant barrage of images that encourage Japanese women to be cute, air-headed, fashion-obsessed, and unthreatening to men. Even though the reality is far from that, there’s no denying that Japanese society itself often cultivates this image since it remains a male-dominated society that superficially wants women to be more empowered in society and the workplace but still expects them to fulfill traditional roles of servitude in the home. So while I recognized the reasons why Bacigalupi created the ‘windup girl’ character, I really disliked this choice. Even more, he graphically describes the sexual humiliations that Emiko undergoes in two extended sequences that turned my stomach. Perhaps this was meant to show just how disgusting men are when it comes to dehumanizing women and reducing them to sex objects, but it was over the top and nasty. There’s a fine line between describing evil behavior and just being gratuitous.

Actually, this entire book is filled with unsavory characters like the Somdet Chaopraya, the real power behind the Thai throne; General Pratcha, head of the Environment Ministry and its white-shirt goons who shake down business owners, and Trade Minister Akkarat, who is in bed with various foreigners seeking a foothold in Thailand and is also scheming to overcome Pratcha. There is also Cavanaugh, a businessman who is even more unpleasant than Lake. There is even a sleazy gene-hacker named Gibson who cares more about the challenges of designing new genetic creations and will work for either side. In a world as ruthless and resource-depleted as this, perhaps this is realistic, but everyone is so self-serving, callous, scheming, and mean-spirited that it just wore me down as a reader.

There were only three characters not completely unpleasant. Hock Seng, an older ethnic Chinese man who escaped Islamic extremists in Malaysia, the Green Headbanders, who slaughtered all the Chinese they could find in an orgy or religious fervor (and revenge for economic grudges). Hock Seng lost all his formerly prosperous family in Malaysia, and has been reduced to a subservient position as a supervisor in Anderson Lake’s factory. His goal is to steal plans for a new kink-spring design and somehow revive his decimated clan. I certainly could sympathize with his plight, and saw parallels with how the Nazis seized the property and money of Jews in Europe under the cover of ideology.

The most interesting character is perhaps Captain Jaidee, a former muay thai boxing champion who works for the white-shirts of the Environment Ministry. Although most white-shirts are on the take and look the other way as farang (slang for foreigners) smuggle in contraband, he decides one day to destroy the shipments at the docks to send a message that the Thais are not completely in thrall to foreign powers. While this generates a big groundswell of popularity among the downtrodden, he also angers the vested interests inside the ministry and other powerful enemies. His desire fight corruption is admirable but inevitably doomed to failure. His lieutenant Kanya later makes a fateful decision that will change the fate of Thailand and the various powers vying for control.

The pacing of the book is quite problematic too. It starts fairly briskly, as we see the sweltering, teeming streets of Bangkok and learn how this world works. However, not much happens for the middle 200 pages other than learning lots of details about the unpleasant characters mentioned about, before the plot suddenly leaps into action, leading to a muddled power struggle that eventually erupts in to open civil war between the Trade and Environment ministries. Several ‘deus ex machinas’ are used to arrive at a seeming conclusion, before things are flipped at the end and new possibilities are suggested. The rushed ending and chaotic fighting among various parties reminded me of the last 100 pages of Neal Stephenson’s The Diamond Age (the steampunk and biotech aspects are also related), and was equally unsatisfying. Since this was Bacigalupi’s first novel, it would be great if he has polished his craft and learned to combine his excellent world-building with better pacing and more sympathetic characters. However, from the reviews I’ve read of his subsequent YA dystopian books Ship Breaker and The Drowned Cities, as well as his most recent book Water Knife, he seems to prefer uncompromising tales of environmental disaster that serve as dire warnings against the direction we are heading. All very good, but it wouldn’t hurt to make his books a little more reader-friendly. I felt the same way about William Gibson’s Neuromancer, Count Zero and Mona Lisa Overdrive when I read them 25 years ago. Either way, I plan to tackle two of Gibson’s more recent near-future thrillers Pattern Recognition and The Peripheral at some point, but will have to be prepared for some heavy reading.

~Stuart Starosta

I had a similar experience and decided to put the book on my “backburner” list for another time. A shame really.

I have not read this book yet, but I’ve read the short stories set in this world — they were superb.

Best book I couldn’t finish. We will meet again someday The Windup Girl…someday

Excellent review, Marion. You articulated many of the feelings I had when reading the book, but never managed to write out in a coherent way. It’s a flawed but excellent book, and especially for a debut it’s a stunning achievement. My favorite works by Bacigalupi are contained in the “Pump Six and Other Stories” collection.

Yes, Pump Six and Other Stories is excellent.

I think Pump Six will be next on my list of his, but Shipbreaker, which is YA I think, looks intriguing too.

I agree with you. Although there are raving reviews of this book, it was difficult to follow and I couldn’t connect with the characters. I’m not complaining about the difficulty of following the politics because the same goes towards George RR Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire series which is still a great series otherwise. Being halfway through it, there were no point in the book that moved me. We are introduced into the deepest thoughts of the characters, yet there is a barrier. I’m not sure if I should continue reading or not.

There are many who love this book, and I can understand why they do. However, I was never able to connect with the story in any meaningful way. There are many others that have echoed similar sentiments. I was told things get twisty in the latter half of the book, so you might want to stick it out. Let us know how it went if you did.