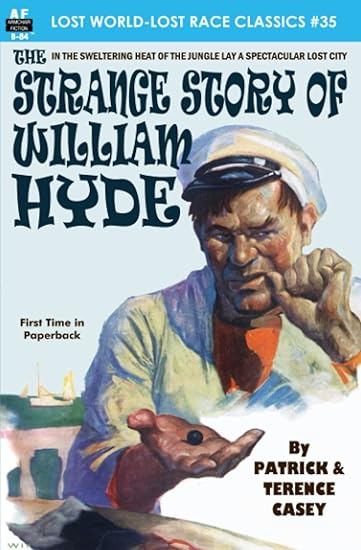

![]() The Strange Story of William Hyde by Patrick & Terence Casey

The Strange Story of William Hyde by Patrick & Terence Casey

In 1886, Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson came out with one of his most enduring creations, the novella entitled “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”; a work that has rarely – if ever – gone out of print since its initial release. But this would hardly be the last “strange” story featuring a character by the name of Hyde! Thus, 30 years later, on the other side of the pond, the world was given a book bearing the title The Strange Story of William Hyde; a book that turned out to be anything but a publishing perennial, despite its manifold fine qualities, as will be seen.

In 1886, Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson came out with one of his most enduring creations, the novella entitled “The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde”; a work that has rarely – if ever – gone out of print since its initial release. But this would hardly be the last “strange” story featuring a character by the name of Hyde! Thus, 30 years later, on the other side of the pond, the world was given a book bearing the title The Strange Story of William Hyde; a book that turned out to be anything but a publishing perennial, despite its manifold fine qualities, as will be seen.

The Strange Story of William Hyde first saw the light of day as a hardcover book released by Hearst’s International Library in 1916. It would then go OOPs (out of prints) for a good 105 years (!), until the fine folks at Armchair Fiction saw fit to resurrect it for a modern-day audience in Fall 2021, as part of its ongoing Lost World/Lost Race series. And thank goodness that the editors there decided to do so, as a recent reading has shown the book to be an absolutely first-rate contribution to the genre. The novel was written by the San Francisco-born brothers Patrick (1892 – 1941) and Terence (1894 – 1945) Casey, who, in their teens, had already had any number of short stories published in the adventure pulp magazines of the day, such as, uh, Adventure. This lost-race offering seems to have been the brothers’ first published novel (hard facts on the team are difficult to come by), and three more books would soon follow: The Wolf-Cub: A Novel of Spain (1918), The Gay Cat: The Story of a Road-Kid and His Dog (1921), and a collection entitled Hobo Stories, featuring short tales of those American wanderers, written from 1914 – 1921. Thus, The Strange Story of William Hyde would seem to be the team’s only genre novel, and what a terrible pity that is, as the book really is a remarkably fine one, and a must for all fans of this kind of fare, as initially popularized by the great H. Rider Haggard, six years before Patrick’s birth.

The Caseys’ book is narrated to us by a young American sailor named Colum Kildare, who sets sail from San Francisco looking for adventure. In the Hawaiian Islands, Kildare twice bumps into a “shell-and-pea” grifter who is conning the locals out of their money. On the second occasion, while the crew is on shore leave on Kauai one evening, the conman – an enormous, blue-eyed, red-haired and red-bearded chap, with hideous scars on his abdomen – flees from the angry locals and swims to the ship on which Colum stands guard duty alone. Also swimming up to the ship, at the same moment, is a British gent named Fitzhamon, who seeks refuge on the craft for reasons of his own. Kildare brings the two refugees belowdecks and gives them dry clothes and drinking stuffs, after which the two older men have a brutal fight and Fitzhamon is knocked out cold. And then, as the red giant – who, as it turns out, is another Englishman, by the name of William Hyde – begins to imbibe his second bottle of liquor, his tongue is loosened, and he tells Colum of the greatest, strangest, and most tragic adventure in his entire career.

Twelve years earlier, we learn, Hyde had disappointed his father by not becoming a lawyer (in the same manner that Haggard had disappointed his old man), but rather, a hunter of rare orchids. While engaged in a search for the exotic Coelogyne Lowii flower in the interior of the world’s third-largest island, Borneo, his Dyak guides had pointed out to him an extinct volcano, inside of which supposedly dwelt a people called the Poonan, who worshiped a priceless relic called the Green, Green God. No person had ever ventured into the precincts of the Poonan and returned, but Hyde had decided to make the attempt, alone, and purloin the relic if he could. And, remarkably, Hyde had indeed discovered a tunnel entrance into that volcanic lair, at the enormous crater bottom of which he’d discovered a city called Jallan Batoe, with animal-shaped stone dwellings, a sphinxlike temple, cultivated crops, and the Poonan themselves, who had greeted him with both amazement and awe. His blue eyes and red beard, apparently, were the cause of the people’s consternation (this Armchair edition’s front cover erroneously depicts Hyde as being clean shaven!), and Hyde would go on to spend three nights and two days with the Poonan, first as an honored guest, then as a feared king, and finally as an evildoer to be slain.

Hyde, during the course of his short stay, had fallen in love with the Poonan queen, Belun-Mea Poa-Poa (Marshal Queen of the Golden People), an auburn-haired, green-eyed beauty; made a bitter enemy of the suspicious high priestess Lip-Plak-Tengga (Flower of the Silver Star), after Hyde rejects her lustful advances; learned that he himself bears a striking resemblance to Genghis Khan (whose armies had conquered Borneo and whom the modern-day Poonan are descendants of), thus being given the name Man-Child of Genghis Khan; become the instant husband of the queen, after giving her an innocent kiss; and been made a hunted and despised enemy of the people, after being set up (no, I really shouldn’t reveal in what manner) by that scorned and wicked priestess. And as if all that hadn’t been enough to keep Hyde busy when he wasn’t playing a game of Hyde and seek for his very life, Lip-Plak-Tengga had also held in her command a dreaded creature known only as the “Monster Man,” with which Hyde had had two casual and one very unfortunate run-in. Hyde’s tale is a lengthy one, not concluding till the next morning, and by the end of which young Colum Kildare is left slack-jawed with amazement. And such, I have a feeling, will be the case with all his readers!

Hyde, during the course of his short stay, had fallen in love with the Poonan queen, Belun-Mea Poa-Poa (Marshal Queen of the Golden People), an auburn-haired, green-eyed beauty; made a bitter enemy of the suspicious high priestess Lip-Plak-Tengga (Flower of the Silver Star), after Hyde rejects her lustful advances; learned that he himself bears a striking resemblance to Genghis Khan (whose armies had conquered Borneo and whom the modern-day Poonan are descendants of), thus being given the name Man-Child of Genghis Khan; become the instant husband of the queen, after giving her an innocent kiss; and been made a hunted and despised enemy of the people, after being set up (no, I really shouldn’t reveal in what manner) by that scorned and wicked priestess. And as if all that hadn’t been enough to keep Hyde busy when he wasn’t playing a game of Hyde and seek for his very life, Lip-Plak-Tengga had also held in her command a dreaded creature known only as the “Monster Man,” with which Hyde had had two casual and one very unfortunate run-in. Hyde’s tale is a lengthy one, not concluding till the next morning, and by the end of which young Colum Kildare is left slack-jawed with amazement. And such, I have a feeling, will be the case with all his readers!

Now, in my reviews of some other books in this Armchair series, such as those for David Douglas’ The Silver God of the Orang Hutan (1922) and S. P. Meek’s The Drums of Tapajos (1930), I complained that those novels were done in by a dearth of forceful and convincing detail, but happily, that is not the case with the Caseys’ book here; quite the opposite, as a matter of fact. I’m not sure if the brothers ever traveled to the Hawaiian Islands, the Borneo interior and the various Far Eastern locales name-dropped in their novel (again, hard facts about the two are a challenge to unearth), but the reader will surely be convinced that they did. The amount of research demonstrated in their novel is most impressive, lending their tale a welcome patina of verisimilitude and genuineness. Thus, we learn much about the food and drink of the region, the flora and fauna, the various tribes, the Indonesian sailing vessels, the history of Borneo, its geography and so on. And we get to know a lot of the Indonesian, Malay and Dyak words for many of the items discussed; just about everything is legit here, and not made up, with the exception of the fact that it was Genghis Khan’s grandson, Kublai Khan, who in actuality invaded Borneo in 1292, and not the old man. (Wackadoodle that I am, I checked all these things so that you won’t have to.)

Their book is also filled with many imaginative touches, such as those animal-shaped stone homes (Hyde happens to be put into an elephant-shaped one), and the Singing Stones at the bottom of the volcanic crater, which store up the equatorial heat of the day and release it at night, accompanied by weird ululations. Borneo, home of one of the planet’s oldest rainforests, makes for a perfect and unusual setting for one of these lost-race novels, and the Caseys do a nice job at describing the locale. To their credit, their story is beautifully well written (it’s hard to believe that this was their first attempt at a full-length tale) and features both a lovely heroine and a truly hissable villainess. The book’s story line grows more intense and suspenseful as it proceeds, culminating with an agonizingly breathtaking windup and a lovely coda. And the brothers provide us with any number of superbly well-executed sequences along the way, including that brutal, early fight between Hyde and Fitzhamon; the priestess’ vivid descriptions of the war between Khan’s Tartars and the Dyaks 600 years earlier; Hyde’s ascension to the throne and marriage “ceremony,” a sequence that takes up a full quarter of the book; Hyde and his bride’s attempts to undo the priestess’ mischief (yes, I’m trying to be coy and not reveal any spoilers here), in the dead of night; the couple’s absolutely thrilling escape attempt from Jallan Batoe; and, of course, Hyde’s mano-a-mano battle with the Monster Man, about whom the less said, the better. To be succinct, The Strange Story of William Hyde is a novel that is practically unputdownable, and one that most readers will regret was never followed up by a sequel, as the Caseys could easily have arranged, had they so chosen.

As for William Hyde himself, I hope that I haven’t given you the wrong impression when I described him as being a “conman” earlier. As it turns out, he is quite the likable fellow, and his reason for trying to scrounge up cash in whatever manner possible is explained by his story’s finish. Even while drunk, and following a brutal and punishing fight, Hyde manages to tell a wonderfully worded story, all the while revealing himself to be a decent, intelligent (although he does make any number of mistakes while residing with the Poonan!) and well-educated man. Really, would a poorly educated man ever use such words as “sudorific,” “etiolate,” “pleach,” “silique,” “bosque” and “nide”? And the man is even capable of a lovely turn of phrase here and there. Take, for example, this description of his bride:

…Her lips were as soft as roses, as warm as life itself, as moistly sweet as honey, and as fragrant as the flowers of some sweet dream with that delicious breath of her. I drank of them as of some heady delirious wine…

And his description of the wicked priestess:

…I saw for a surety now that she was sublimely beautiful – her nose sensitively chiseled and imperious as Minerva’s, her buds of bosoms quickly rising and falling, like fretful wavelets, beneath the daring diaphaneity of her orchid gown, and her skin, where it was visible, as sleekly golden as the soft bed of dreams…

Gee, I wish I spoke that eloquently when I was drunk!

I actually have only three quibbles to lodge against the Caseys’ work here, two small and one more serious. One minor matter is the fact that Hyde is forced to bind and gag one of the Poonan courtiers and secrete him in the left-hand entrance of his elephantine home; a little later, we are told that this Poonan was still laying in the right-hand entrance. Another minor matter is a brief instance of casual racism that the reader encounters, when it comes time for a description of that Monster Man. But most serious for me was the novel’s flawed story format itself. As I said, this book is narrated to us by young seaman Kildare, based on his memories of what Hyde had told him during a long night of drinking. But is it really possible for anyone to have recalled this tale with the degree of specificity and plenitude of detail that young Colum gives us here? Of course not! Thus, I can’t help feeling that the book would have worked a lot better had it taken the form of an autobiography written by Hyde himself, based on his own recollected firsthand experiences, instead of coming to us secondhand. Had it been presented to us in that manner, as were Haggard’s Allan Quatermain tales, it would be receiving a perfect grade from yours truly, instead of the near-perfect grade that I am forced to give it here.

Still, The Strange Story of William Hyde really is a wonderfully entertaining yarn that I cannot recommend to you strongly enough. A “harebrained, staggering story,” Colum calls it early on, and I would surely agree with that staggering part. To my very great surprise, this has turned out to be one of the very best lost-race tales not written by H. Rider Haggard – and even far superior to Haggard’s own 1909 novel The Yellow God – that I’ve ever read, and those who know of my great esteem for all things Haggard will recognize that as a great compliment, indeed. “One of the most imaginative, well done books of its kind,” author Jessica Amanda Salmonson once wrote of this book, and I could not agree more…

We’re in total agreement David!

I felt just the same. The prose and character work was excellent. The larger story was unsatisfying, especially compared to…

Hmmm. I think I'll pass.

COMMENT Was I hinting that? I wasn't aware of it. But now that you mention it.... 🤔

So it sounds like you're hinting Fox may have had three or so different incomplete stories that he stitched together,…