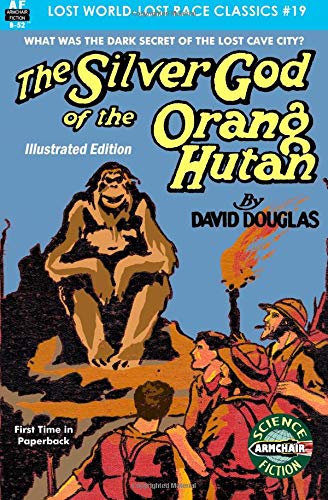

![]() The Silver God of the Orang Hutan by David Douglas

The Silver God of the Orang Hutan by David Douglas

As many of you here at FanLit may have already discerned, this reader is a huge fan of English author H. Rider Haggard, and at this point I have read 45 of the man’s 58 novels. Haggard, for good reason, has been called “The Father of the Lost Race Novel,” and his influence on that genre has been enormous, casting a very long shadow across the decades since he came out with the triple whammy of King Solomon’s Mines, its sequel Allan Quatermain, and the seminal fantasy She, all in the mid-1880s. Haggard has had many imitators, many of whom have been forgotten over the intervening decades. Happily, a new series from the Medford, Oregon-based publisher Armchair Fiction is now available that just might prove manna from heaven for all fans of such Haggardian fare. This Lost World/Lost Race series consists of no fewer than 24 titles, many of which I’d never heard of before. Of those two dozen books, this lost-race fan had previously only read eight (Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, Francis Stevens’ The Citadel of Fear, Abraham Merritt’s The Metal Monster and The Face in the Abyss, Haggard’s She and The Yellow God, C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne’s The Lost Continent and William Hope Hodgson’s

As many of you here at FanLit may have already discerned, this reader is a huge fan of English author H. Rider Haggard, and at this point I have read 45 of the man’s 58 novels. Haggard, for good reason, has been called “The Father of the Lost Race Novel,” and his influence on that genre has been enormous, casting a very long shadow across the decades since he came out with the triple whammy of King Solomon’s Mines, its sequel Allan Quatermain, and the seminal fantasy She, all in the mid-1880s. Haggard has had many imitators, many of whom have been forgotten over the intervening decades. Happily, a new series from the Medford, Oregon-based publisher Armchair Fiction is now available that just might prove manna from heaven for all fans of such Haggardian fare. This Lost World/Lost Race series consists of no fewer than 24 titles, many of which I’d never heard of before. Of those two dozen books, this lost-race fan had previously only read eight (Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Lost World, Francis Stevens’ The Citadel of Fear, Abraham Merritt’s The Metal Monster and The Face in the Abyss, Haggard’s She and The Yellow God, C. J. Cutcliffe Hyne’s The Lost Continent and William Hope Hodgson’s

The Boats of the Glen Carrig), which left me a good 16 to catch up with. Choosing at random, I dove into one of the titles that was completely new to me, The Silver God of the Orang Hutan, by David Douglas.

I wish I could tell you more than the scant facts that are researchable regarding this title, but there just isn’t a lot out there, and this Armchair Fiction release from last year sheds very little light on the subject. As far as I can make out, the novel was initially released in 1922 by the English publisher C. Arthur Pearson, Ltd. This hardcover volume featured seven full-page illustrations by one R. D. Farwig (happily, included in the new edition) and today sells for around $65 online … if you can find a copy. The book was never reprinted until Armchair saw fit to do so; so yes, it had languished in almost complete obscurity for something like 96 years. No information on its author seems to be available anywhere, but I am assuming that Douglas was also an Englishman; The Silver God of the Orang Hutan is his only novel, as far as one can tell. A pleasing combination of jungle adventure and lost-world shenanigans, the book, simply written as it is, just manages to please.

Douglas’ novel introduces us to wealthy American businessman Silas K. Horton, who had decided to venture into the interior of the Malaysian Peninsula to ask permission of the natives there to open a tin mining operation. Horton had also learned of a legendary relic, the titular silver god of the Orang Hutan tribe — the eyes of which are said to be made of the largest rubies in the world — and had decided to make off with that priceless prize as well, if possible. Thus, Horton hires an experienced English hunter named Harry Boone (and I can only assume that Boone is English, because so much emphasis is placed on Horton being an American) to act as his guide, and away the two go, into the nearly trackless jungle depths, only accompanied by Boone’s two sons, 18-year-old Harry and 17-year-old Dan (yup, that’s right … Daniel Boone!), both experienced hunters and “dead shots,” like their old man, as well as Senik, a trusted Malaysian servant. Boone himself has an ulterior reason for making the hazardous journey; namely, he is searching for his brother Jack, who had been captured and probably killed by the head-hunting tribe led by the chieftain Nabi Alang. The quintet encounters any number of dangers, of both the human and wild animal variety, before approaching the vicinity of the Gunong Pahang, the so-called “Forbidden Mountain” of the Orang Hutan tribe, from which area no white explorer has ever returned. And when our brave heroes ultimately do encounter the pint-sized inhabitants of the region, who are in perpetual warfare with the tribe of Alang, it would seem as if their odds of venturing out from the Malaysian wilderness have similarly been reduced to zero…

As I mentioned earlier, Douglas’ book is a rather simply written affair, and indeed, the writing style forcefully suggests that The Silver God of the Orang Hutan was intended as a boys’ adventure story; what we might today call a “YA book.” Those readers who have ever experienced, say, a Hardy Boys novel will perhaps have some idea of the style in question here. The book’s easy readability, thus, makes it a rather fast-moving experience for adults, and the cliff-hanger nature of practically every chapter will surely keep the reader flipping those pages. This is a lost-race novel with nothing in the way of fantasy or sci-fi content, unlike most of the other titles in the 24-book Armchair series, I have a feeling. Though fairly unlikely, it is just possible for all of the events in Douglas’ book to have actually transpired in our mundane world. Thus, it is a fairly credible lost-world adventure, its unlikeliest aspect being that of a pygmy race living inside of a cave city beneath a honeycombed mountain. As these kinds of tales go, it is a fairly realistic conceit.

Douglas, to his credit, keeps the reader constantly bombarded with any number of action set pieces. Before our intrepid band ever reaches the Forbidden Mountain, it encounters murderous Malay pirates, a shark attack, rampaging sladangs (Malaysian oxen), red ants, leeches, a rogue elephant, crocodiles, treacherous natives, and a fearsome panther. Once arrived at their goal, they must then contend with blowgun-wielding pygmies, a bevy of killer orangutans (you probably saw those coming, right?), and finally, an attack by those pesky headhunters. No wonder the inside cover of this Armchair edition proclaims “A monstrous beast in darn near every chapter!” From beginning to end, the book does not let up for a moment. And Douglas, again to his credit, shows that he had done his homework before penning his one and only book. Hence, we get to read of the Malaysian kris (dagger), those killer sladangs, the native lalang grass, the sumpitan (the blowgun that the pygmies employ to shoot poisoned arrows … not darts!), the Penanggal (a headless ghost woman of Malaysian myth, whose possible appearance midway through the book marks the novel’s closest brush with the fantastic), the upas tree with which the pygmies make their poison, and the sago starch that the Orang Hutan folk are shown eating. Though not depicted in any great depth, our four main characters here are all hugely likeable, and each gets his chance to shine heroically, saving the lives of his fellows on more than one occasion. So yes, it is a fun, fast-moving and enjoyable affair, overall.

Still, there are many problems, and in the interest of complete honesty, I am compelled to say that Douglas, at bottom, was not a very good writer. His verbiage is distinctly unlovely; functional, at best. He is guilty of fuzzy descriptions on any number of occasions, and does not seem to care much about the rhythm and sound of his sentences; thus, “…Harry, who was now almost at the point of exhaustion, promptly ceased his strength-using kicking, and trod water…” The men’s entrance into that Forbidden Mountain was frustratingly difficult for this reader to envision, too. And Douglas also gives us an occasional line so ungrammatical as to render it senseless, such as “Till that moment, although subconsciously both boys had known that their father and Horton were engaged in as grim a battle as they themselves had fought, grimmer in fact, seeing that there were half a dozen of the brutes arrayed against them.” Senseless, right? That is, until one puts a comma after the word “subconsciously.” The whole book is like that, replete with awkward phraseology, faulty punctuation and unclear descriptions. All three offenses are ones that H. Rider Haggard was hardly ever guilty of committing; the difference between a professional master (and man of genius, sez me) and a talented amateur, which Douglas undoubtedly was. Based on the evidence here, Douglas showed great promise, only needing the practice of years and more writing to hone his craft … not to mention a good copy editor. Perhaps that editor might have noticed that the hill called Changdak Asah — which our band is compelled to climb at one point — is said to be 500 feet high on page 75 and 700 feet high on page 83. Not being able to keep facts like this straight is a cardinal sin for any writer, I would say. So bottom line: David Douglas is no H. Rider Haggard, but that was probably to be expected going in, right? And like I said, his sole effort does manage to entertain.

Oh … one final thing. While I am grateful to Armchair Fiction for making this book available after almost a century of neglect, and do applaud their very impressive catalog of books available (loads of unusual sci-fi and fantasy titles, aside from this Lost Race series), I must also chide them for the deplorable presentation here. This volume, #19 in their Lost Race series, contains so many typos that it really does become quite unacceptable, after a while. And not just simple typographical errors: Punctuation is often missing; “Harry” becomes “Barry” a half dozen times; “friends” becomes “mends”; “soft” becomes “80ft” (!) and so on. Whether this book was reset for its new edition or these pages were simply photographed directly from the 1922 hardcover, I do not know. What I do know is that the reader deserves better. To be fair, I have already purchased a few other Armchair volumes, and a quick skim reveals that they look to be typo-free. I do look forward to getting into both of those volumes very shortly, and only hope that they have been brought to market with more care and attention than has The Silver God of the Orang Hutan…

The presence of the two teen boys suddenly makes sense, if this were meant as a “boys’ adventure.”

I am so sorry about the bad writing! Frankly, the title had already decided me that this was not for me. Naming a “hidden” tribe after orangutans shows, at best, a complete lack of imagination. And that’s at best.

Well, at least the author managed to explain the presence of orangutans in Malaysia, although they are only found in Borneo and Sumatra. I’m hoping for better things in those remaining 15 books. Stay tuned….