The novelettes nominated for the Nebula Award this year are so dissimilar that it’s going to be difficult for the judges to compare them and make a decision. Ranging from hard science fiction to the softest of fantasy, these stories are a testament to the breadth of the field. Ruth Arnell and I teamed up to take a look at the seven nominated stories.

One of the nominees is from the pages of Analog: Eric James Stone’s “That Leviathan, Whom Thou Hast Made.” Its central character is Harry Malan, the president of the Sol Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints – a church that exists at the heart of the sun, adjacent to the interstellar portal that exists there. The story does not explain how humans came to discover this portal, or the energy shield that allows humans to exist at the core of a star, literally in the middle of an ongoing fusion reaction – but then, that’s not an issue that would be of particular interest to a Mormon funds manager for CitiAmerica who has been stationed at Sol Central in order to get an eight-and-a-half minute jump on the market.

One of the nominees is from the pages of Analog: Eric James Stone’s “That Leviathan, Whom Thou Hast Made.” Its central character is Harry Malan, the president of the Sol Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints – a church that exists at the heart of the sun, adjacent to the interstellar portal that exists there. The story does not explain how humans came to discover this portal, or the energy shield that allows humans to exist at the core of a star, literally in the middle of an ongoing fusion reaction – but then, that’s not an issue that would be of particular interest to a Mormon funds manager for CitiAmerica who has been stationed at Sol Central in order to get an eight-and-a-half minute jump on the market.

There are only six human members of the Mormon congregation in the sun. There are, however, forty-six swale members. Swales are a species made of plasma, and have existed for millions of years before mammals even began to appear on earth. They are huge creatures, the smallest being double the length of a blue whale. And they are apparently immortal, for Malan soon has a confrontation with Leviathan, the biggest and the oldest of the swales, who claims to be the first of her kind who created all others – to be, in fact, God. When she challenges the Mormon faith of a young swale due to the interference of Malan, the young swale is forced to decide between religions. In an extremely pat ending that would work better in a religious text than a science fiction magazine, it’s Christianity to the rescue.

James Patrick Kelly’s “Plus or Minus” is the hardest science fiction story of this group. It takes place on an “asteroid bucket” – a spaceship that sticks to our solar system mining asteroids. Mariska is a teenager who has been gene-engineered to hibernate, which her mother hoped would mean that she would embrace a career exploring deep space. But like teenagers everywhere and everywhen, Mariska resents her mother’s interference in her life, and joins the crew of the asteroid bucket. It’s not as good a rebellion as she thought it would be, though, as she finds herself mostly on “crud duty” – disinfecting the mold and fungus that grows all over the spaceship. But when disaster strikes, Mariska has to figure out a way to help the crew survive the fact that it doesn’t have enough air to get home. If you’re looking for a scientific riddle, this is the story for you. Indeed, it reminds me of the granddaddy of all hard science fiction stories, Tom Godwin’s “The Cold Equations.”

“The Jaguar House, in Shadow” by Aliette de Bodard, appears to take place in an alternate universe where the Aztec rule of Mexico was never overthrown, and the modern country is a political power to be reckoned with. The story is one of political machinations, and the science fictional details are surplusage; one does not need the imminence of intelligent computers to explore whether a leader’s betrayal of the deep beliefs of her constituency was good or bad. It’s a beautifully written story, in an interesting culture, but the plot does not hang together as well as it should.

“The Fortuitous Meeting of Gerard Van Oost and Oludara” by Christopher Kastenschmidt is apparently an introduction to the title characters, a Spanish explorer in Brazil and a slave he buys and frees so that they might together explore the thick forests and their monsters during the sixteenth century. It’s a fine adventure tale of humans matching wits with magical creatures, but Terry was really puzzled at its inclusion on the Nebula ballot. The story is no better or more interesting than dozens of other adventure tales published in the last year; why was this one singled out?

“The Fortuitous Meeting of Gerard Van Oost and Oludara” by Christopher Kastenschmidt is apparently an introduction to the title characters, a Spanish explorer in Brazil and a slave he buys and frees so that they might together explore the thick forests and their monsters during the sixteenth century. It’s a fine adventure tale of humans matching wits with magical creatures, but Terry was really puzzled at its inclusion on the Nebula ballot. The story is no better or more interesting than dozens of other adventure tales published in the last year; why was this one singled out?

“Stone Wall Truth” by Caroline M. Yoachim originally appeared in the February 2010 issue of Asimov’s. It appears to take place in an alternate Africa that was once visited by an alien race. The only remnant of that race is a wall and tools by which to use its special properties. Njeri is the wielder of those tools, the one who pins alleged miscreants to the wall and flays them while they are alive, then resews them and restores them to life. The punishment is intended to show the darkness hidden within the criminals, for it comes crawling from their bodies when they hang there, open to the world. But one woman whom Njeri sews up challenges Njeri’s belief that the darkness is evidence of evil, and causes her to question the policy of treating the latest political outcasts in such a manner – and thereby calls the punishment down on herself. Njeri learns in the course of her flaying that the original use of the wall was something much different from how she and her people now use it. It leads to an ending that would have been much powerful if it weren’t for the fact that the same result reached through enormous pain could as easily have been achieved by writing and reading books. As good as the writing is here – and it is quite good – the mechanism behind the plot just seems silly when one takes a hard look at it.

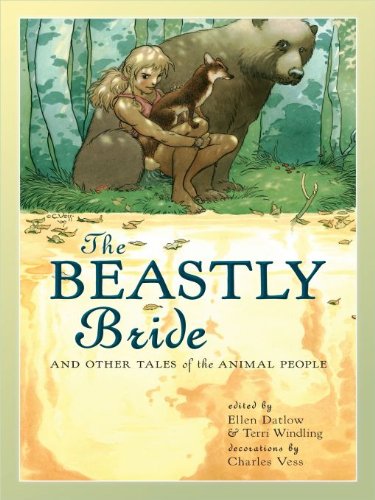

Two of the nominated novelettes were part an original anthology of young adult fairy tales edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, The Beastly Bride. The first is “Map of Seventeen” by Christopher Barzak. Ruth didn’t much care for this story, finding the plot line was trite and predictable. To her, this story differed from the usual star-cross lovers tale only in that it dealt with two males instead of a male and a female – not a sufficient difference, even if one of the men was a beast of sorts. Ruth found the story too similar to Holly Black’s “A Coat of Stars” from her anthology The Poison Eaters, another tale about an artistic gay brother who came home from NYC to a culture that doesn’t accept him, bringing along a magical love interest – a story that Black did better. Still, these objections would not have bothered her overly much, because one doesn’t necessarily expect much innovation in a collection of modern fairy tales for young adults. But Ruth found it odd that the entire story was told through the eyes of an unsympathetic minor character. Her momentary glimpse of a hidden reality was supposed to be a paradigmatic shift for her, but Ruth believes she’s been dealing with issues like this since she was seven. Ruth found Barzak’s story oddly flat, an attempt to be “meaningful” or “literary” rather than good, a prosaic account of someone growing out of their teenage angst into young adult idealism. She found it to be an average piece of writing, and was surprise at its nomination.

Two of the nominated novelettes were part an original anthology of young adult fairy tales edited by Ellen Datlow and Terri Windling, The Beastly Bride. The first is “Map of Seventeen” by Christopher Barzak. Ruth didn’t much care for this story, finding the plot line was trite and predictable. To her, this story differed from the usual star-cross lovers tale only in that it dealt with two males instead of a male and a female – not a sufficient difference, even if one of the men was a beast of sorts. Ruth found the story too similar to Holly Black’s “A Coat of Stars” from her anthology The Poison Eaters, another tale about an artistic gay brother who came home from NYC to a culture that doesn’t accept him, bringing along a magical love interest – a story that Black did better. Still, these objections would not have bothered her overly much, because one doesn’t necessarily expect much innovation in a collection of modern fairy tales for young adults. But Ruth found it odd that the entire story was told through the eyes of an unsympathetic minor character. Her momentary glimpse of a hidden reality was supposed to be a paradigmatic shift for her, but Ruth believes she’s been dealing with issues like this since she was seven. Ruth found Barzak’s story oddly flat, an attempt to be “meaningful” or “literary” rather than good, a prosaic account of someone growing out of their teenage angst into young adult idealism. She found it to be an average piece of writing, and was surprise at its nomination.

Terry, on the other hand, thought it an excellent story. She believed that Meg was the absolute center of the story from beginning to end, and that the older brother’s return to the homestead was merely the occasion for her to be shaken from a sort of small town, down on the farm complacency that she doesn’t even recognize she holds. Terry doesn’t believe it is ever clear that Meg has been dealing with a sort of supernatural power – the ability to impose her will on others – from the age of seven, but rather wonders if that perceived ability isn’t really a childish inability to recognize that people will sometimes do as she wants just because it’s so obvious from her face and demeanor how hurt she would be if they didn’t. The brother and his husband are interesting characters, but they are mere foils here, almost beside the point to Meg’s maturation over the summer before she starts college. Terry found Barzak’s story to be one of the stronger of the novelettes nominated and, unlike Ruth, would not be surprised if it were to win the Nebula.

The other novelette from The Beastly Bride is “Pishaach” by Shweta Narayan, an immersive tale of Shruti, a young woman growing up in India. When her grandfather dies, her grandmother disappears; she has returned to her existence as a Naga, a snake. But before she disappears, she tells Shruti that she, too, is Naga, and tells her how to ensure her transformation when she reaches puberty. Bequeathed with the secret for reclaiming her snake form, Shruti goes mute, refusing to interact with the human world anymore. When her transformation ritual is interrupted and she is stuck forever in human form, Shruti has to learn how to negotiate a world where she is denigrated for being female and a danger because everyone can tell that her strange affection for snakes is a sign of not normal. Shruti illuminates some of the beastly characteristics of humanity – fear, ostracism, and abuse of power – and reveals some of the simpler, more honest characteristics of snakes. The resolution to the story isn’t exactly a happy ending, but rather a claim about the way that those that society rejects can find happiness out of the limited options they have available to them. Narayan is quite convincing at creating fully realized characters and settings within a short format which is a difficult feat. This novelette resonates with mythic weight. Ruth thinks it is a serious contender for the win; Terry believes it is the clear winner.

COMMENT Was I hinting that? I wasn't aware of it. But now that you mention it.... 🤔

So it sounds like you're hinting Fox may have had three or so different incomplete stories that he stitched together,…

It's hardly a private conversation, Becky. You're welcome to add your 2 cents anytime!

If the state of the arts puzzles you, and you wonder why so many novels are "retellings" and formulaic rework,…

I picked my copy up last week and I can't wait to finish my current book and get started! I…