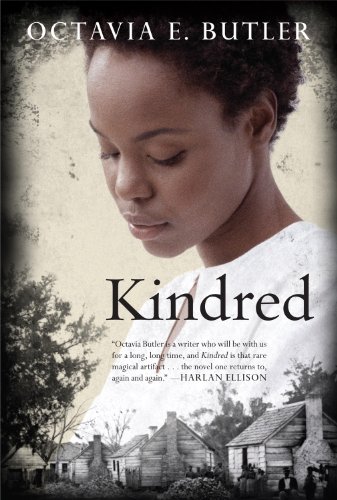

![]() Kindred by Octavia Butler

Kindred by Octavia Butler

Kindred (1979) is Octavia Butler’s earliest stand-alone novel, and though it features time travel, it’s not really science fiction or fantasy. It’s an exploration of American slavery and its painful legacy from the eyes of a contemporary (well, circa 1976) young black woman named Dana. So don’t expect to learn why she keeps being pulled back in time to a pre-Civil War slave plantation in Maryland every time her ancestor, a white slave owner named Rufus Weylin, finds his life in danger. It’s a plot device that allows the reader to experience all the horrors of being a powerless black female slave in 1815 while retaining a modern perspective. So this book is firmly in the tradition of Alex Haley’s Roots (1976), Alice Walker’s The Color Purple (1982), and more recently the Oscar-winning film 12 Years a Slave (2013) in describing the impact of slavery and poverty that still leaves its marks on the American psyche today.

As the first prominent black woman science fiction author to emerge in the late 1970s, it’s not surprising that Butler would want to write a story concerned with the position of black women in both contemporary society and the past, and give it a science fiction framing device. The story of Kindred is deceptively simple, but Butler does not take the expected route of merely showing us the evils of slavery. Instead, she tackles a much more difficult subject: the strange and twisted relationship between white slave owners and their black slaves, one in which cruelty, oppression, and dehumanization are mixed with paternalism, religious condescension, and White Man’s Burden. The question she asks is straight-forward: what would a contemporary young black woman do when forced into a position of subjugation under an ignorant and vicious white slave owner and his young son, if that young man was her own distant ancestor?

Dana is a young black woman in Los Angeles, working low-paid temp jobs via an employment agency that she and others jokingly refer to as economic slavery. She aspires to be a writer, but has never found a way to make this dream a reality. At one of her jobs she meets another aspiring writer, Kevin, an older white man who she becomes friends with. Neither of them are living the American dream. Their families are not approving of their interracial relationship, and life is not easy, but they find comfort in each other and their common interests, and eventually get married.

On her 26th birthday, she feels dizzy and loses her senses. When she comes to, she sees a young white boy struggling to avoid drowning in a river. She wades in to save him, but is soon after confronted by an angry white woman, his mother, who assumes she is hurting him, and then confronted by a shotgun-wielding man, his father, who points his gun at her. At that point she is transported back to her L.A. apartment with Kevin. Neither understand what happened to her, and Kevin initially struggles to believe her, but he quickly adjusts to the situation after she is repeatedly transported back in time, always to a moment when Rufus is in danger, though each time she goes back he is a little older, and the relatively short time spend in the past is much longer in the present. Knowing that it can happen without warning, Dana and Kevin prepare supplies to help her survive in the past. Interestingly, they make no attempt to describe the situation to anyone else, assuming they will be considered insane.

With this pattern established, the bulk of Kindred details Dana’s increasingly longer stays in antebellum Maryland. While Rufus’s father Tom is a vicious and ignorant man, regularly beating and intimidating his slaves to ‘keep them in their place,’ young Rufus is initially just another little boy learning from his environment. He accepts the world around him — white men are at the top of the hierarchy, followed by white women, and then black men and women are essentially subhuman property (slaves) that are there to serve white people and should be beaten down at the slightest hint of resistance. Each time we meet Rufus, he is a little older and a little more like his father, yet retains some signs of decency in his strange relationship with Dana. Because Dana is clearly educated, despite being a black woman, both Rufus and his father Tom are unsure how to categorize her. Her intelligence and knowledge are intimidating, but when she talks back to them they react violently, either beating her or using psychological violence to suppress her.

Butler forces us to experience Dana’s situation, trapped as a slave but with full knowledge of the future, and shows unflinchingly just how deep-rooted the slave and slaver mentality is ingrained in whites and blacks alike. It’s a telling detail that religious ministers find convenient passages in the Bible to justify the relationship of slave and master, something we also see in the film 12 Years a Slave. The other slaves on the plantation resent Dana, since she talks like an educated white person, and gets special treatment as Rufus’ tutor. Notably, Rufus is attracted to a strong-willed slave named Alice, whom he initially approaches peacefully, but when she rejects him he rapes her instead, blaming her for being difficult.

Over time, Rufus fathers several children with Alice, all against her will. Throughout this process, he continues to want Alice to like him and is continually frustrated by her refusal to accept his overtures. Rufus demands that Dana intercede on his behalf, but she is torn. She knows that one of their children will become her ancestor, so she cannot prevent her own future existence. Even when she desperately wants to kill Rufus for his casual cruelty to her and Alice, she always hesitates for that reason.

I’ll leave further plot details for readers to discover on their own, but the relationship between Alice, Rufus, Dana, and Kevin becomes every more complex, until events come to a violent and cathartic head. The entire story is emotionally-wrenching, since it is impossible not to imagine ourselves in Dana’s position, and yet that is truly unimaginable for any modern person. Or is it? Dana’s early life in L.A., while not subject to arbitrary beatings, is little different from economic slavery. The disapproval of her relationship with Kevin by their families shows the persistent nature of racism even in the world of 1976.

But the central question, one that really bothered me throughout Kindred was why both Dana and Kevin slipped so quickly into the mindset of slavery in those dark times. Why does Dana continue to give Rufus the benefit of the doubt, always hoping he will be more kind and compassionate than his cruel father, only to be disappointed again and again? And why doesn’t Dana resist her slavery more aggressively, perhaps trying to arrange an underground railroad to free slaves like Harriet Tubman (something that Kevin alludes to). Instead, the powerlessness of her situation, the psychological oppression and fear of beatings wears down her will to fight, and she has the benefit of a modern upbringing. How much harder would it be for slaves raised from birth to question or fight back against oppression? There are many cases of blacks running away in the story, but they are constantly hunted down, brutally beaten, and sold off farther south. One of the cruelest methods the Weylins use to keep their slaves cowed is by deliberately selling off their children, whether fathered by Tom or Rufus or the black male slaves, just the way you’d sell livestock. By casually severing the bonds of parent and child, they crush all will to resist. This was truly the most sickening aspect of slavery in the book, as if the beatings, rapes, and hardship were not enough.

Initially I found it difficult to accept the possibility that any contemporary woman could eventually fall into an uneasy relationship with a white slaver owner, even given the unique (and artificial) plot constraint of him being Dana’s distant ancestor. I’m sure we would all think we’d rather slit Rufus’ throat, run away, or even take our own lives rather than ‘sleep with the enemy.’ But Butler doesn’t let us off the hook so easily. We could never know the real answer unless we were actually thrown back in time, like Dana, as a powerless black woman at the mercies of cruel and ignorant white masters. And yet Butler also depicts these men with fairness — they have moments of compassion once in a while, but they continually revert to the slaver mindset when pushed, and this is not hard to believe since that was the standard of the times.

It would take a truly strong willpower to resist all the accepted beliefs of the time to fight against slavery, and yet somehow that was accomplished when slavery was abolished after the Civil War. Sadly, though the institution officially disappeared, as in stories like The Color Purple, black poverty has continued to persist long after the Civil War ended. Even in Dana’s contemporary world, economic slavery remains, though it is not restricted to blacks. So although Kindred is not particularly uplifting, it does make the reader confront the slave/slaver relationship in all its complexities, and perhaps to understand it better in the end.

The audiobook was narrated by Kim Staunton, who has an extensive theatre, television and film-acting career, and graduated from the Julliard School. She has narrated a number of audiobooks that focus on the stories of African Americans, and does an excellent job on Kindred. It’s a delicate balancing act to handle the Southern accents of uneducated whites and blacks back in pre-Civil War Maryland without straying into stereotype territory, but I thought she was convincing. She also alternated this with the modern voices of Dana and Kevin, and I was really impressed with what she did with Kevin, as he started with a modern voice but after many years trapped in the past, his voice started to take on the speech patterns of the period. Very well done.

Stuart, what a thoughtful review of a great, and difficult, book! I had a lot of your questions when I first read it; I wanted Dana to “fight back” in some way, too. I’ll have to read it again; I think that my “need” is more about my comfort level than about the realities of slavery.

Thanks for bringing this book to people’s attention again! It’s a good one.

Ta-Nehisi Coates wrote some notes when Django Unchained was released that are apropros:

http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2013/01/toward-a-more-badass-history/266997/

“If you read William Still’s compendium of escapes, you find very few revanchists. Instead you see an incredible number of people who escaped, not because of the labor or torture of slavery, but because a relative was sold or because they, themselves, were about to be sold to family. Slave revenge has the luxury of making slavery primarily about white people. It is a luxury that the black rebels of antebellum America had little use for. Uppermost in their minds was not ensuring that white slavers got what was coming, but the preservation and security of their particular black families. Their husbands and wives were not objects to be avenged, but actual whole people whose welfare was more important than payback.”

http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2012/06/thoughts-on-slavery-black-women-and-django-unchained/258228/

“I worry about rendering enslaved black men as eunuchs restored, and enslaved black women as merely the field upon which that restoration is demonstrated. The fact is that is that very few enslaved black women had the luxury of waiting on freedom via black men. In so many cases, they had to make their own way. That is where I believe the nectar of narrative awaits.”

In Kindred, Dana’s primary concern is survival, not revenge; and in fact she plays out this exact drama several times in the novel — turning her white husband’s focus away from retribution toward a survival that requires what may seem like moral compromise and even compassion for her enemies. Butler spares nothing in describing monstrosity, but also, by humanizing the enslavers, highlights the moral complexities of the situation endured by the enslaved.

Interesting stuff, Matt, thanks! I thought when I first read the book that part of its power was an unflinching look at slavery. Probably back then I wanted the escape of fantasy, but Butler had other ideas. Her work always addresses honestly the need, at times, to compromise, even with someone who has done appalling things.

Matt, thanks for sharing that article on Django Unchained. I actually held off for a long time before seeing that film, but when I did finally watch it, it was with very mixed feelings (Tarantino generally produces that response in me). It is a unabashed revenge fantasy against slavery and white oppression, carried out by the charismatic Jamie Foxx and his strange white companion Christoper Waltz, on the nastiest white slavers you could possibly conjure up. Somehow I suspect this movie is still aimed at white audiences wanting to root for a black man taking revenge against their own racist/slave-owning past. A way to expunge an ugly legacy and feel like “that isn’t me, I hate slavery and racism.” And since it’s Tarantino, it is of course ridiculously violent and over-the-top. But the film still left a bad taste in my mouth for some reason.

Coates’ Atlantic article makes the very salient point that revenge against slave owners was a luxury, and the top priority was survival and reuniting with family. It was that urge, even more than a desire to escape beatings and privation, that drove slaves to run away. I can imagine that any short-lived revenge would result in a more vicious backlash that would claim many innocent lives of those nearby as convenient targets.

The fact that Dana continually redirected her white husband Kevin away from exacting revenge on the Weylins is certainly a brave narrative choice. It would have been much more Tarantino-like if he just went gangbusters and murdered every slave owner he could find and started a popular revolt, thereby changing history. If only it were so easy. The more I reflect on the book’s choices, the more I appreciate Butler’s courage in promoting compassion and humanizing both sides and avoiding an indiscriminate call for vengeance.

Yeah, it was probably my least favorite of Tarantino’s films. I read Kindred last year (actually I, like you, listened to Kim Staunton’s excellent narration), and Coates’s articles were still fresh in my mind. (My wife also does scholarship in womanist (i.e. black feminist) philosophies, in which ‘survival of self and progeny’ emerged historically as the highest moral good over against honor and truth and courage and fairness and etc.) And it’s not just in Butler’s historical writing here; you can see the same ethic at work in Parable of the Sower and its sequel.

It strikes me in Coates’s and in Butler’s writings that they have an enormously generous moral imagination, ably denouncing evil while being able to clearly imagine themselves committing the same evil under the same circumstances. It lends itself to a fierce sort of compassion — a compassion that is the complement of a just and dignified rage.

Thanks for your lengthy review; it’s always good to hear others’ perspectives on interesting works of fiction. Kindred (like much of Butler’s writing) still feels pretty contemporary (and very relevant) even though it’s pushing 40 years old.

Matt, I’m planning to tackle all three of her major series this year: Patternist, Xenogenesis, and Parable. I heard she struggled to produce a third Parable book and wrote Fledging instead. And then inexplicably had a stroke and died at age 58. That is truly a loss to the SF/literary world.