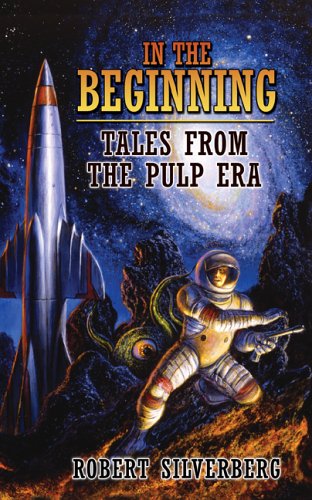

![]() In the Beginning: Tales from the Pulp Era by Robert Silverberg

In the Beginning: Tales from the Pulp Era by Robert Silverberg

I’ve been enjoying reading Silverberg’s early story collections lately, and I particularly enjoy that he, like his friend Harlan Ellison in his story collections, includes not only an autobiographical introduction to the book, but also memoir pieces before every story. As a result, his collections become two books in one: part short story collection and part portrait of the artist.To be honest, I think I like both parts equally.

In the Beginning: Tales from the Pulp Era consists of sixteen stories written from 1955 to 1959. It overlaps in time period with To Be Continued (1953-1958): Volume One of The Collected Stories of Robert Silverberg (the definitive collection); however, the two books do not print any of the same stories. For Silverberg fans, then, both books are essential. In To Be Continued, Silverberg refers occasionally to In the Beginning, so I would suggest reading it first.

If one is reading these books in order to get a sense of Silverberg’s artistic development, I would recommend reading Science Fiction 101: Exploring the Craft of Science Fiction (edited with memoir and critical essays by Silverberg) after reading In the Beginning and To Be Continued. Though Science fiction 101 is a collection of SF stories by other writers, Silverberg’s commentary goes along with the two early short story collections in explaining how he developed his craft as a young man.

Silverberg started publishing in 1953, when he was an eighteen-year-old sophomore at Columbia, but In the Beginning: Tales from the Pulp Era opens with a story written and published in 1955, his final year of college. He admits that this collection “represented the side of him that was producing, at improbably high volume, stories intended mainly to pay the rent, stories meant to be fun to read and nothing more.” But he says also that he has never been ashamed of them or “repudiated them” because “for better or for worse, they were part of my evolutionary curve.” And he is certainly right not to be ashamed of them. They are great stories. Here are some of my favorites:

The collection opens with “Yokel with Portfolio” (1955), which begins with a sentence that gets its humor from making perfect sense with the exception of two words: “It was just one of those coincidences that brought Kalainnen to Terra the very week that the bruug escaped from the New York Zoo.” Who is Kalainnen, and what’s a bruug? Those two questions drive the entire story, which is a very funny one as we meet an alien visiting earth. He meets another alien with a similar mission and finds out he will need to spend the bulk of his time on earth standing in lines because of bureaucracy! His fairly pedestrian plight leads into his run-in with the bruug. Which is worse — a series of long lines or a bruug?

In the introduction to “Guardian of the Crystal Gate” (1956), Silverberg tells an embarrassing story on himself: When he was seventeen years old, he wrote a searing essay “for an amateur magazine of s-f commentary named Fantastic Worlds.” In his essay, he critiqued harshly the very same teen pulp magazines he had liked a few years earlier. Editor Howard Browne, who secretly wasn’t even a big fan of SF according to Silverberg, wrote a reply to his “diatribe” that Fantastic Worlds published. As Silverberg notes, Browne’s response was written “quite graciously.” Three years later, Silverberg was writing many stories for Browne for the same magazines he had criticized, using the same conventions, writing to the same young boys, and using the same house names, particularly “Alexander Blade.” Given that three years had passed since this little exchange, Silverberg assumed that Browne didn’t remember anything about it, because Browne both continued to buy stories from him and never mentioned it. At least, that’s what he thought, until one particular day, as Silverberg writes: “During one of my visits to the Ziff-Davis office about this time, Howard Browne greeted me with a sly grin and pulled a small white magazine from his desk drawer.” That’s one of my favorite tales in the entire collection. I just love a good coming-of-age story . . .

The fictional story that follows, “Guardian of the Crystal Gate,” sticks with me visually, and perhaps that’s because it’s based on a picture. Silverberg was given instructions to write a story based on the proposed cover painting which “showed two attractive young ladies in short tunics fiercely wrestling atop a huge diamond.” That image doesn’t bode well for a good story, but Silverberg made it an interesting one, particularly in terms of the villain of the piece, or, I should say, the middleman villain of the story. Don’t get me wrong, the story has all the images and corresponding sex appeal one would expect from a story of its time written to that particular audience, but he makes the story more than just another pulp tale.

Perhaps my favorite story is “The Hunters of Cutwold” (1957). Maybe it’s because Silverberg mentions in the introduction that Somerset Maugham, my favorite writer of short stories in the English language, is one of his favorite writers. Silverberg attributes to both Maugham and Conrad his interest in the following setting and theme: “stories set on alien planets with vivid scenery, involving hard-bitten characters who sometimes arrived at bleak ends.” He even asks scholars who have focused on the influence of Conrad on his later work to “please take note” of the influence of Conrad and Maugham on his fiction even as early as 1957. “The Hunters of Cutwold” is certainly a Maugham-like tale, and Brannon, the main character, is forced to betray the person we all least want to betray: one’s self. I don’t want to say anything else but this: I think this story — from what I’ve read of Silverberg’s early works — is his greatest early work of fiction. I highly recommend this collection for this story alone. “Mournful Monster” (1959) also falls in this thematic category. Perhaps “Vampires from Outer Space” (1959) does as well: It’s certainly one of the finest stories in the collection, and it’s unique in being a police procedural as well.

Though I don’t have the space in a single review to go over in detail all the stories in the collection (and you wouldn’t want to read all those details even if I did!), here are a few teasers for some of the other stories:

“Choke Chain” (1956) is about Jupiter’s largest moon where an entire people have been enslaved by having to wear collars that purify the polluted and otherwise deadly air. The real catch? The collars have meters running and the bills are very costly. And then a stranger comes to town . . .

Instead of telling you the plot of “Cosmic Kill” (1957), I’ll tell you what Silverberg emphasized about it: It’s the one and only work of fiction in his entire career that he wrote on speed. That makes it a curiosity in itself, doesn’t it?

“The Android Kill” (1957) involves prejudice-fueled riots in which many androids are killed by mobs. What would you do if someone you knew claimed that you and your wife were androids? Could you prove you weren’t? Could you figure out why he was making these claims to begin with? And what would you do with that information even if you got it?

“Come Into My Brain” (1958) involves the main character’s entering an alien brain to pry out secrets. What makes it interesting from a post-cyberpunk perspective is that it reads much like the descriptions that became conventions in cyberpunk as people go to battle in virtual reality.

“Exiled from Earth” (1958) will be appreciated by and should be read by any Shakespeare fan: it “involve[s] an old actor out in the stars who wanted to go back to Earth and play Hamlet one last time.” What makes it even better, given the way playhouses were moved for religious reasons in Shakespeare’s day, is that the actors in the story have all been exiled from Earth to begin with because it had come under “Neopuritan” political control! What a great premise. And the ending is incredibly touching.

“Second Start” (1959) is about the practice of rehabilitating criminals so they no longer have any criminal impulses; they are also given new names and given new faces so they won’t be recognized by previous criminal associates. The only choice out of those three requirements is the plastic surgery — one could choose to go to a planet where everyone is a stranger. That’s exactly what the newly named Paul Macy decides to do. And he has a great life until somebody recognizes him.

I enjoyed almost all the stories (with the exception of maybe two), and I would have liked them even if I had not known they were early works of a future Grand Master. I think they are fun and smart and engaging all on their own. How do I know? Because I finished the book! I love short stories, but I rarely read a collection of short stories by a single author or even in a single genre from start to finish. In fact, I often dip into a single collection of stories for years. But I read In the Beginning: Tales from the Pulp Era in less than a week. I was still reading other fiction, but I kept finding myself opening this collection at least once a day until it was over much more quickly than I had anticipated. I’m already halfway through both To Be Continued and Science fiction 101.

The Collected Works of Robert Silverberg — (2006-2013) Publisher: A projected eight volumes collecting all of the short stories and novellas SF Grandmaster Silverberg wants to take their place on the permanent shelf. Each volume will be roughly 150,000-200,000 words, with classics and lesser known gems alike. Mr. Silverberg has also graced us with a lengthy introduction and extensive story notes for each tale. The Subterranean Collected Silverberg will vary greatly from the UK trade paperback series published in the 1990s. Due to the publisher’s desire to limit the series to eight volumes, many stories and, especially, novellas, could not be included. The Subterranean Collected Silverberg will be the definitive set.

Hey, I just read a Silverberg novel from 1972 called “The Second Trip,” which also features a character named Paul Macy who had been brain wiped and rehabilitated. I had no idea that the author had already toyed with this premise 13 years earlier! Anyway, thanks, Brad, for this great review of a book written by one of my favorite sci-fi authors. I haven’t read too many shorter pieces from this amazing (and remarkably prolific) writer, and your review certainly makes me want to start. BTW, DO check out “Downward to the Earth,” if you want to see some bona fide Conrad influence in Silverberg’s work….

Thanks, Sandy! I really appreciate your comment here since I wouldn’t even be reading Silverberg if it weren’t for your reviews!

I’ve got Second Trip lined up in my reading cue, as well as Downward to Earth and all the Silverberg novels you’ve recommended so far. But I’ll probably work through the VERY early novels first because I’m enjoying seeing Silverberg’s craft develop over time.

This morning, I wrote a draft of my next Silverberg review: His 1956 novel The 13th Immortal, which I greatly enjoyed.

I’ve ordered his first novel, Revolt on Alpha C, because I’m curious to see what this 1955 novel is like. The other novels I plan to read before Downward to Earth are as follows: The Chalice of Death, Stepsons of Terra (Shadows on the Stars), Starman’s Quest, Starhaven, The Planet Killers, The Plot Against Earth, Planet of Death, One of Our Asteroids is Missing, To Open the Sky, Thorns (I loved your review), Hawksbill Station (The Anvil of Time), The Masks of Time (Vornan-19), Across a Billion Years, Up the Line, and To Live Again.

What I find amazing is that my list skips about 14 novels he wrote during this same period of time before Downward to Earth! Honestly, for the most part, I’ve decided to read the ones that were easiest to get my hands on.

I’ll be reviewing his short short story collections as well as these early novels for the summer. By the time I get to his major works, I’ll be dying to read them. But I love short, early SF novels, so I’m having a blast.

If you read any more of these early novels (I know you’ve already read some and reviewed some, particularly in the collection of three novels In Times Three), I hope to see that we end up with some side-by-side reviews of the same novels.

Speaking of Conrad, I just listened on audible to Silverberg’s excellent The Secret Sharer, which is both the title of a Conrad story and a reinterpretation of that story in SF format. It’s a wonderful novella and well-read. The audible version comes with two other stories, and I’m still listening to those — when I’m finished, I’ll write a review.

And because I’m interested, I have cued up on my Kindle Conrad’s “The Secret Sharer,” which I think is in public domain.

One warning about Silverberg, Brad: The dude CAN prove addictive! Take it from me! Anyway, so nice to hear that you’re having fun with these great old works from an acknowledged master. I look forward to reading your takes on all of them!