![]() Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie

Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie

Breq used to be a spaceship, or at least a fragment of the spaceship known as Justice of Toren. The ship controlled innumerable human bodies, known variously as “ancillaries” to the people of the interstellar Radchaai Empire and as “corpse soldiers” to the cultures and planets the Empire has conquered. Those soldiers used to be regular, innocent human beings who, if sufficiently healthy, were slaved to one of the Radchaai ships, their personalities more or less overwritten to become part of one of the Empire’s many-bodied artificial intelligences.

But note: Breq “used” to be a spaceship. Now, she is just Breq, a single person with one body, but with memories of being both an immensely powerful artificial intelligence and its army of soldiers. When we meet Breq, at the start of Ancillary Justice, the spectacular debut novel by Ann Leckie, she is hunting for a gun — a gun that may be able to kill Anaander Mianaai, the immortal and multi-bodied Lord of the Radch.

Ancillary Justice starts off alternating between two perspectives, who happen to be the same person. Sort of, at least. One set of chapters focus on Breq’s present, her search for the semi-mythical gun that may be able to kill the leader of the Empire she used to serve, and her encounter with a drug-addicted former officer of that Empire. The second set of chapters consists of flashbacks to Breq’s past, except she wasn’t Breq then — she was One Esk, a squad of twenty corpse soldiers serving on Justice of Toren, and at the same time she was Justice of Toren itself, serving during one of the Radchaai’s “annexations” (read: brutal subjugation of an entire planet’s population).

Ancillary Justice may quite possibly be the most unique and refreshing take on space opera I’ve encountered since I discovered the works of Iain M. Banks, years ago. It could also, in some ways, be read as a comment on some of that author’s works in specific and on the space opera genre in general — but more about that later.

This is a deceptive novel, one that will challenge many of the expectations you may have about SF as it eases you into its story. One of those expectations is the gender of its protagonist and side characters. Tell me you weren’t surprised when, in the second paragraph of this review, Breq turned out to be a she. Now multiply that surprise a hundredfold, and you will have an idea of what this novel does so successfully.

The language of the Radchaai Empire does not differentiate between gender. Breq uses “she” and “her” throughout the story to refer to other characters. Occasionally you only find out a few chapters later that one of those characters is actually male. Sometimes, Breq must force herself to pay attention because she realizes that people from other cultures may take offense to being called the wrong gender.

In this context, when someone refers sneeringly to Breq as a “tough little girl” in the very first chapter of the novel, it’s hard not to take it as a comment on the casual sexism so often displayed in SF — partly because of what Breq used to be, and partly because of the culture she belonged to.

The blindness to gender also has a much more bitter connotation, given the way the Radchaai deal with conquered empires, treating prisoners as bodies to be enslaved, whether they’re male or female. Depersonalization is a big theme of this novel: people are re-educated (read: brainwashed) or turned into ancillaries as a matter of course. It becomes clear fairly quickly that the Radchaai Empire almost makes Nazi Germany look like nice folks. Concentration camp guards probably didn’t really care about the gender of the people filing into the gas chambers either.

In that sense, the dispassionate tone of the chapters told from One Esk’s perspective is utterly chilling. The fact that she occasionally narrates from various viewpoints (the twenty bodies she controls) is only a small part of that. It’s really the sense that she’s part of a vast, horrible, and incredibly successful war machine — and the sense that most people inside that war machine believe they’re doing the right thing, spreading the equivalent of the Pax Romana across the universe. One Esk collects songs from the cultures the Radchaai have assimilated, then sings them, in harmony with the other bodies she controls. It’s one of the most chilling images I’ve ever encountered in a science fiction novel.

But then there’s that second plot, where Breq — again, one of Justice of Toren’s former components — is trying to bring change to the system. Every other chapter essentially shows Breq as a one woman revolutionary army. Ancillary Justice is the story of how she got from here to there, and while that story develops it also introduces the book’s spectacularly innovative and fascinating space opera universe. It’s almost impossible to believe that this novel accomplishes so much in under 400 pages.

So, about that Iain M. Banks comparison earlier. I should probably first explain that I tend to compare every space opera I read to his CULTURE novels, because in my opinion they’re the gold standard for the genre in almost every way. However, in this case, there were a few items that really struck my attention. Names like Seivarden Vendaai, for one, wouldn’t look out of place in a CULTURE novel. More importantly, the classification of ships (Mercy, Sword, Justice being different categories) reminded me of things like the ROU’s and GOU’s.

Those are all details, however, and probably could be traced back to other series too. Much more significant is the seemingly diametrical contrast between the two societies: the semi-anarchist, post-scarcity, almost Utopian Culture, and the fascist, dystopian Radchaai which goes as far as treating prisoners as a commodity, stockpiling bodies by the millions for possible future use. Both societies are highly reliant, if not governed by, impossibly powerful artificial intelligences, but whereas the Culture lets its human run free and wild, the Radchaai exercises the ultimate form of control.

And yet, both are, well, empires, right? One of the main ongoing plot threads in the CULTURE series is the way it interacts with other civilizations. Departments like “Contact” and “Special Circumstances” have subtle names — but you could have a long discussion about the ethical underpinnings of their philosophy as much as the Radchaai’s. Ancillary Justice makes the reader question the many forms of imperialism and colonialism as much as the perception of gender.

So, please forgive me for that long sidebar about an entirely unrelated series. I truly found it hard not look at this stunning debut novel as a deeply complex challenge to some long time SF tropes.

There’s a lot more to Ancillary Justice than what I’ve touched on here. Several SF planets and individual cultures. A set of incredibly subtle relationships and personal histories. A narrative tone that’s somehow at once dispassionate (which makes sense, given who’s narrating) and richly textured. On the negative side, I felt that the story did lose some tension towards the end, when the two threads merge. And, it’s the start of a series, which I wasn’t aware of when I started reading. Because of this, the ending felt like a bit of a letdown. I was ready to give this novel five stars, something I very rarely do, but I ended up settling for 4.5 because of those minor quibbles.

And yet. Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie is, so far at least, the SF debut of the year. It’s a book that will have you reconsidering its many implications for a long time after you turn the final page. I can’t recommend it highly enough.

![]() Wow! What a read! Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie grabbed my attention from the first paragraphs, when Breq, a humanoid who was once a soldier, finds an unconscious body in the snow.

Wow! What a read! Ancillary Justice by Ann Leckie grabbed my attention from the first paragraphs, when Breq, a humanoid who was once a soldier, finds an unconscious body in the snow.

There was something itchingly familiar about that outthrown arm, the line from shoulder down to hip. But it was hardly possible I knew this person. I didn’t know anyone here. This was the icy back end of a cold and isolated planet, as far from Radchaai ideas of civilization as it was possible to be.

Breq appears to be a soldier and so does the figure in the snow, Seivarden. Seivarden is a drug addict coming off a high, and will only slow Breq down, but she helps Seivarden anyway.

These two characters have more in common than either of them first realize. Each is a lost soul. Seivarden was in a state of suspension for a thousand years, after the loss of a starship in a battle. Breq was Justice of Toren, a Radchaai battleship. I could say that she was the AI of that ship, but Justice of Toren was a being with a consciousness that was not separated from her physical self, any more than my hand would call my brain its AI. As well as knowing every aspect of herself as a ship, Justice of Toren had eyes, ears and minds on the surface of any planet she orbited through the use of “ancillaries,” human bodies augmented with implants and loaded up with Justice of Toren’s consciousness. Twenty years ago, in a shocking act of sabotage, Justice of Toren was destroyed except for the one remaining ancillary who calls herself Breq.

Leckie enfolds us in the concept of a distributed consciousness through masterful use of point of view. Breq is a first-person narrator in the “present tense” part of the story, even if that narrator has two thousand years of direct experience to draw from. In the backstory sections, as Justice of Toren, the point of view, still first-person, ranges among Justice of Toren’s many nodes of awareness. In the tale’s present tense, Breq searches for a unique weapon, needed for her final act of vengeance.

If Leckie had done nothing more than give us a vengeance quest that explored collective consciousness, Ancillary Justice would still be an engrossing read. She reaches much farther than that, showing us a complex, elaborate culture; musing on the nature of empire and conquest; contemplating the purpose of religion and depicting a highly stratified, rule-bound society that is facing changes it doesn’t understand.

The forward momentum of the story of Breq’s search flags slightly at the end of the first third of the book, but the back story is so puzzling and suspenseful that it carries us over that slack patch. Leckie’s descriptions are lovely; the temples, Breq’s icons, and the baskets of flowers ready to be purchased for offerings all stand out, as does the use of music and song. With a single well-placed sentence Leckie demonstrates how traditions evolve in a society.

… Directly ahead stood the temple. The steps were not really steps, but an area marked out on the paving with red and green and blue stones; actions on the steps of the temple potentially had legal significance.

All of this could be cool and slightly abstract, except that Breq is a real character; complicated, flawed and ultimately heroic. Secondary characters like Seivarden and the two Radchaai lieutenants, Awn and Awer, are well drawn, as is the Ruler of the Radch, who is a fascinating adversary. Once we understand Breq’s quest and her motivations, we root for her even though we realize that what she seeks to do is impossible.

Ancillary Justice is a masterful achievement. The pacing is right, deep and serious concepts unfold as we ride along on an adventure that grows increasingly tense and intense with each passing scene. Not many science fiction writers can make a conversation that happens over tea and pastries nail-bitingly suspenseful, but Leckie manages.

Finally, if you know someone who still insists that words like “mankind” and “his” are inclusive and general rather than exclusive, have them read this book just for what Leckie does with the pronouns. This stylistically challenging choice not only opens a window into Justice of Toren’s worldview, it makes us think about our own assumptions of language and gender.

Since I’m not a big fan of military SF, which some might consider this book to be, I wasn’t sure how much I would like it. This was a delightful surprise. Ancillary Justice is a book of big ideas wrapped in a gripping four-star adventure.

~Marion Deeds

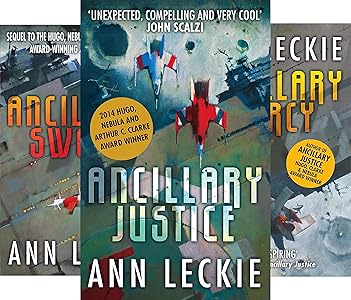

![]() Sometimes debut novels just strike a chord and win a bunch of awards, and Ancillary Justice was a deserving recipient. It won the Hugo, Nebula, Arthur C. Clarke, BSFA, and Locus awards for Best Science Fiction novel in 2013. It’s a flashy and intricate space opera that is strongly reminiscent of Iain M. Banks’ CULTURE series, but also takes a new approach to gender that echoes Ursula K. LeGuin’s masterpiece The Left Hand of Darkness. Its most interesting invention is a believable depiction of distributed consciousness, both for AIs and humans. It takes some getting used to, but that’s part of the fun of this exciting new epic.

Sometimes debut novels just strike a chord and win a bunch of awards, and Ancillary Justice was a deserving recipient. It won the Hugo, Nebula, Arthur C. Clarke, BSFA, and Locus awards for Best Science Fiction novel in 2013. It’s a flashy and intricate space opera that is strongly reminiscent of Iain M. Banks’ CULTURE series, but also takes a new approach to gender that echoes Ursula K. LeGuin’s masterpiece The Left Hand of Darkness. Its most interesting invention is a believable depiction of distributed consciousness, both for AIs and humans. It takes some getting used to, but that’s part of the fun of this exciting new epic.

Stefan Raets’ and Marion Deeds’ reviews excellently describe the world and characters of Ancillary Justice, so I will just add my thoughts on the bold ideas this book introduces. The main character Breq is an ancillary, a human body whose mind has been wiped clean and has one fragment of the consciousness of a sentient ship (Justice of Toren) inserted. It takes the reader time to figure out exactly what Breq is in her solo form, and even more time to understand the complex hierarchy of the Justice of Toren ship with its mixed ancillary and human crew, and its mission on the planet Shis’urna, which is being annexed into the Radchaai Empire.

The intricate social and political structure of the Radchaai rivals Frank Herbert’s Dune, but in tone this Empire shares many parallels with the British Empire when it controlled a vast network of colonies. The Radchaai military relies on a rigid command hierarchy, with a Captain in charge, but Ship’s intelligence is so pervasive that it’s unclear who has greater control. Social interactions among the Radchaai are also very formal and intricate. Much is implied and there is a constant battle beneath the surface for status, recognition, family honor, patronage, etc. In case it wasn’t obvious enough, the human members of the Empire crave tea and cakes as the highest form of civilized leisure. In fact, the term “Radchaai” is equivalent to civilization, and thus all members are citizens, and all humans outside the fold are, therefore, barbarians. It is okay for barbarians to be killed, enslaved, and otherwise absorbed into the Radchaai Empire, because this is a process of civilizing them, Manifest Destiny in a science fiction guise.

From the beginning we are shown the victims of this intricate and expansionist Empire, led by its immortal leader Anaander Mianaai, Lord of the Radsch. The moral questions that arise from the ruthless conquests of the Empire are not asked by its citizens, but instead by the barbarians whose resistance is futile, and even more interestingly, by the ancillary Breq, in the unique position of being a fragment of a ship AI. Because ship AIs themselves are subservient to their human Captains, despite superior intelligence, capabilities, and understanding. The status of AIs is an ambiguous one among the Radchaai, and yet they are heavily dependent on them for their military power and station administration. So as Breq’s independent personality develops over the course of the novel, we gain greater insight into Radchaai society. There is such an overwhelming sense of cultural superiority among the Radchaai towards barbarians that it started to really get on my nerves, which was Leckie’s intention (I believe).

As Stefan pointed out in his review, the Radchaai Empire presents some very interesting comparisons with Banks’ CULTURE. The former is extremely hierarchical and formalized, with an all-powerful human ruler (albeit with a consciousness spread among thousands of bodies), and AIs are there to serve human masters. In the Culture, the balance of power is firmly in favor of the artificial Minds, who have created a sprawling and decentralized galaxy-spanning Empire in which humans play a far smaller role. Instead, the Minds allow human beings to indulge in their own decadent interests and pursuits, thereby keeping them from interfering with their agendas. In fact, it is never exactly clear what the Minds of the Culture are really after, but they (usually) take a more benevolent approach to contact with aliens and non-Culture human civilizations via Contact and Special Circumstances. That’s where most of Banks’ novels take place, in the interactions between the two. His ‘message’ in the series remains elusive, but in its refusal to provide obvious morals it allows readers to draw their own conclusions about the role of humans and AIs in a post-scarcity society.

Meanwhile, the more we learn of Radchaai civilization, the less palatable it becomes. Its casual cultural chauvinism towards other human cultures is quite odious at times, and the fact that thousands of barbarians are routinely rounded up and brain-wiped to provide bodies for ancillaries is never thought of by the Radchaai as anything other than the inalienable right of the superior civilization. They drink tea, after all! For those subject peoples who don’t submit quietly, death is frequently dealt out, but again, what else would you expect? It’s this same cavalier attitude of the British Empire towards its colonies that eventually led to its downfall, and it makes me wonder what is in store in future IMPERIAL RADCH volumes.

There are also some tantalizing mentions of the alien Presger, who in some ways are more powerful than the Radchaii, and preyed on them until a treaty was formed to keep the two empires on peaceful terms. Part of the story here revolves around weapons made by the Presger that cannot be detected by Radchaai technology, and clearly these aliens will play a major role in the series going forward.

Ancillary Justice also garnered a lot of attention for its ambivalent approach to gender. In essence, gender exists in Radchaai society, but really isn’t all that important. Therefore, there is no distinguishing of male and female in the Radchaai language, so they have trouble identifying it among barbarian civilizations. To demonstrate this, Leckie chooses to identify all characters as “she” and “her,” but occasionally throws in “sir” and “him” to confuse things. Radchaai do have males and females, and procreate like normal humans, but gender is just not a big factor. So by continuously using “she” and “her” instead of “he” and “him,” Leckie demonstrates how our own language betrays our built-in biases.

However, although this may superficially resemble the Gethenians in Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, that society consisted of genderless humans who only took on male and female traits during courtship periods, and could adopt either depending on the dynamics of the couple. Le Guin was conducting a thought-experiment of much greater subtlety, imagining what a society without male or female personalities would be like, how it would differ from our own gender-conscious world.

In contrast, Leckie’s Radchaai society has male and female, but doesn’t make a fuss about it. Being science fiction, it’s certainly a legitimate extrapolation to make that after thousands of years, human civilization would not be so hung up on whether we are male or female. The dominant and subservient roles would not be tied to gender anymore, but would arise due to individual personalities. However, I wasn’t entirely convinced by this, since the characters do make reference to sexual attraction and relationships, but only in passing. Is it really possible for sexual relations between men and women to NOT have any meaningful impact in their relative social status and influence? Essentially it’s deliberately left underemphasized in the novel, but that alone does not make it convincing to me. If Leckie really wants to make a case for this, she’ll have to explore these relationships in more detail and demonstrate that they don’t really matter. Especially considering how status-conscious and hierarchical the Radchaai society is, it’s hard to believe that gender would not be one of the many areas in which status and power could be measured.

Overall, I was really impressed by the complex world-building, challenging social ideas, and innovative and believable characters. Ancillary Justice doesn’t read like a first novel at all, thanks to its polished prose and intricate storyline. It also had a lot of humor driven by the strange social conventions of the Radchaai, which I wasn’t expecting (just imagine how horribly uncouth bare hands are). I am eagerly looking forward to the next two installments, and I’m usually not a fan of book series.

~Stuart Starosta

I’m SO curious about this book–it’s on The List. I’m extra curious about the gender pronouns. So you’re saying the default “she” is kind of about dehumanization and sexism? I’d been hoping it was more along Left Hand of Darkness lines, where Le Guin is messing with our own cultural obsession with gender oppositions…I look forward to reading it!

No no, it’s definitely more like Le Guin. I’m sorry – I believe I didn’t deal with that part of it as clearly as I could have. The Radchaai don’t “see” gender like we do. It’s not a meaningful factor in how they look at people. The point I was trying to bring up in that paragraph is really more in the way they deal with other cultures as a whole: people are either “citizens” (meaning: have been assimilated as part of the Empire) or not. If not, they can be turned into ancillaries or destroyed as needed, without any moral qualms. So there’s dehumanization in that sense, but definitely not based on gender.

If anything it’s the opposite: there’s the inability to see *anyone* as a person, but on the other hand there’s the inability to categorize them according to what our culture tends to use as a defining quality, i.e. gender. One is horrible, and one is so open-minded it’s almost inconceivable for us. It’s that contrast that makes the novel such a brain-twister.

Oh, I probably just misunderstood! I was reading fast while I was supposed to be doing work stuff. Sounds awesome!

I’m in the minority, wasn’t wow’d at all by Ancillary. Most of what bothered me about the book was personal taste, but then there is this question, my “parting shot”, as it were:

“Ancillary Justice would be getting just as much positive response if the Radchaai only had the male gender terms, right?”

that said, I’d like to read more from Leckie that is completely unrelated to Ancillary, I’m pretty sure she’s got some short fiction floating around out there. I do not want to form my opinion of her as a writer on just this novel.

I can’t, of course, fault your personal taste on whether or not you liked the book (there are people in this world who don’t like Jonathan Strange and Mr. Norrell, either, and I’ve had to accept it). But I can answer this question:

“Ancillary Justice would be getting just as much positive response if the Radchaai only had the male gender terms, right?”

No, I don’t think it would. I certainly wouldn’t have been as impressed if all the gender nouns were male, and here’s why: It wouldn’t have been nearly so successfully unsettling or politically effective.

If all the characters in a military space epic were referred to as male, well, what’s so revolutionary about that? It would be dangerously easy to ignore, because our default assumption for soldiers and generals and emperors and probably even AI ships would be male. Similarly, I think we’re automatically more comfortable with a “masculine” woman than we are with a “feminine” man (not at all fairly, I might add). If a character is referred to as male, but we later find out she’s female—well, that’s just a Terry Pratchett novel. But the slippage between an assumed-female character who turns out to be male—the cultural shockwave is larger.

Using male pronouns would have served more to erase the female characters, instead of drawing attention to gender as a construct. Referring to them all as female is more jarring, more noticeable, and reverses a cultural stereotype rather than perpetuates one.

I just read a synopsis of this book over at io9. With that and your review, I’m definitely interested. All the stories that explore the nature of consciousness are grabbing my attention right now.

Good to hear. All the hype put this on my must-read list as well, but I have yet to make time for it. After reading your review, I think it just climbed another few notches to the top of the pile.

Definitely one of the best books I’ve read in a long time. My only regret was that I had to sleep and couldn’t finish it in one sitting! I can’t wait to see what Leckie comes up with next.

Incidentally, if anyone is interested in other stories by Leckie, the website http://www.freesfonlineDOTde lists nine that are currently available. (The site links to material in on-line magazines, on home pages, publisher’s websites, etc., both in audio and/or as reading copies).

I can’t wait to read this. But I must… too many review books in my stack.

The AI/ship-consciousness bit combined with her pronoun usage had me a bit confused initially, but once I got a feel for what she was doing I really enjoyed this book. One of the best I read last year.

Thanks Marion.

CTGT, I found that point of view (those points of view?) challenging at first too, but she pulled it off.

Obviously, I certainly noticed the pronoun choice, but it didn’t give me any trouble while reading. I notice a few commenters reacting to that choice, though.

For some reason, I’ve been highly resistant to picking this up. But when Marion starts with “wow” and ends with “masterful”, I have no choice but to head to the Kindle store. Really. No choice. I’m trying to stop my hand, but it’s ignoring me . . .

“Talk to the hand!”

Bill, it also has a cover that does it no “justice” whatsoever.

What exactly happens when Breq jumps of a bridge to save Seivardan and they fall into a “hole”? How did they get out? This is similar to Iain Banks in Look to Windward where an engineered human drops to catch a stylo. Who cares if the scenes involving grade school physics makes no sense?

Hi, Karl. Thanks for reading us!