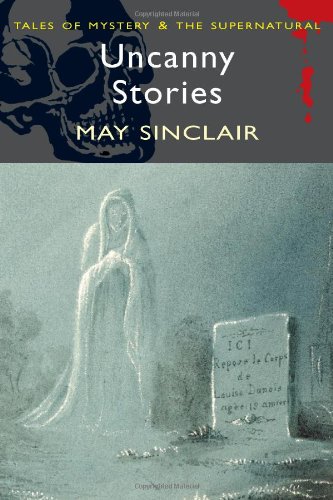

![]() Uncanny Stories by May Sinclair

Uncanny Stories by May Sinclair

This is not the first time that I am going to say some nice things about London-based publisher Wordsworth Editions, and, more particularly, its Tales of Mystery & the Supernatural division, which, over the years, has brought forth dozens of reasonably priced books by many well-known writers, as well as many lesser-knowns. Previously, I have written here of two Wordsworth volumes by some (to me) known authors, Ambrose Bierce (Terror By Night – Classic Ghost & Horror Stories) and Robert E. Howard (The Haunter of the Ring & Other Tales), as well as two authors who were brand-new to this reader, Alice and Claude Askew (Aylmer Vance: Ghost-Seer). And now, thanks to this fine British imprint, I have been introduced to another wonderful writer of the macabre, May Sinclair (1863 – 1946); a most interesting woman, as it turns out. Sinclair was not only a proponent of the then-new Modernist school of writing, but was highly interested in metaphysical matters (such as the philosophies of Immanuel Kant and Georg Hegel) as well. She was at one time an ardent feminist and, as a member of both the Medico-Psychological Clinic and the Society for Psychical Research, an investigator into the occult. And here’s a trivia fact for you: Sinclair is believed to be the first person to use the expression “stream of consciousness” as it pertains to literature.

How do I happen to know all this? The Sinclair book that I recently finished, Uncanny Stories, which was first released in 1923, is here prefaced by a scholarly and informative introduction by one Paul March-Russell. In this intro, March-Russell tells us that “…Sinclair had been one of the most intellectually driven of writers, pursuing the ‘new’ and the ‘modern’ in philosophy, psychoanalysis, mysticism and the paranormal. Her Uncanny Stories … are of a piece with both her ideas and her life-story…” The eight tales contained in this volume are anything but empty-headed, and indeed, several of them are quite challenging. The subject matter ranges from tales of the afterlife to traditional hauntings, but not one of the stories is told in the traditional manner. The ghosts depicted herein are more apt to be looking for affection than to affright; heaven and hell are both like nothing you have encountered before; a murderer may get away with his crime scot-free, while the seemingly innocent are made to suffer. One of the stories is virtually indescribable, while another effectively morphs into a discussion on recondite philosophical matters. But one thing they all have in common is the unexpected. There really is no way for the reader to predict how any of these literate, beautifully written and truly uncanny stories will turn out. These tales don’t so much scare readers while they take them in as haunt them after the story is done, seamlessly combining the traditional, Victorian ghost tropes of the 1800s with the psychological concerns of the early 20th century. The result is both eerie and modern; a most winning combination, to be sure.

As for the stories themselves, the collection kicks off with the unusually titled “Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched.” Here, the reader encounters Harriott Leigh, an unmarried woman who is having a love affair with the married man Oscar Wade. Harriott longs for something more spiritual in their trysts, while Oscar seems perfectly content with just their physical couplings. The two break it off, and decades later, on her deathbed, the still unmarried Harriott decides not to confess about this affair to her kindly priest. After her death, Harriott goes straight to Heaven. Or is it? Wherever she wanders, she runs smack into Oscar … her mate, it would seem, for all eternity. Surely, a hellacious idea for anyone who’s ever felt a little smothered in a relationship, right? Thus, an adult, sophisticated and yes, haunting story to get the ball rolling.

As for the stories themselves, the collection kicks off with the unusually titled “Where Their Fire Is Not Quenched.” Here, the reader encounters Harriott Leigh, an unmarried woman who is having a love affair with the married man Oscar Wade. Harriott longs for something more spiritual in their trysts, while Oscar seems perfectly content with just their physical couplings. The two break it off, and decades later, on her deathbed, the still unmarried Harriott decides not to confess about this affair to her kindly priest. After her death, Harriott goes straight to Heaven. Or is it? Wherever she wanders, she runs smack into Oscar … her mate, it would seem, for all eternity. Surely, a hellacious idea for anyone who’s ever felt a little smothered in a relationship, right? Thus, an adult, sophisticated and yes, haunting story to get the ball rolling.

In “The Token,” our female narrator tells us of her brother, Donald Dunbar, and how he had been haunted by the ghost of his late wife, Cicely. An emotionally aloof man, Donald had treated his wife badly, especially when she had dared to touch one of his prized possessions, a Buddha paperweight given to him by the famous English novelist George Meredith. Now, Cicely’s ghost has begun to haunt Donald’s private library, seeking the affection that she never got from her husband while alive (and hardly the only love-starved spirit in the Uncanny Stories collection, as will be seen). This is a charming story, really, with a lovely ending that will surely move the reader.

Next up we have what is likely the most challenging tale in this bunch, the novella-length “The Flaw in the Crystal.” This is the indescribable story that I mentioned earlier, and indeed, I despair of giving you a proper feel for just what an unusual experience it is. In a nutshell, the story deals with Agatha Verrall, another unmarried woman who is having an affair with a married man, Rodney Lanyon; a chaste affair, it would seem. Agatha is the possessor of an almost supernatural gift: She can mentally compel people to come to her from a distance, as well as soothe the mind back to normalcy and away from madness, as becomes apparent when a couple, Milly and the paranoid and neurotically unbalanced Harding Powell, moves into Agatha’s secluded valley. But her simultaneous attempts to use her mental abilities on both men at once, long term, result in numerous problems, leading to some hallucinogenic episodes and the germ of fear to be born in Agatha’s own mind, the so-called flaw in the crystal that prevents her from tapping into her arcane abilities. A story very much ahead of its time, and one that might have easily fit into the sci-fi New Wave of the mid-1960s, this is one unique reading experience, indeed.

In “The Nature of the Evidence,” Edward Marston is made a widower when his beloved wife Rosamund passes away. But before her passing, Rosamund had told her husband that she wished him to remarry one day, but only with “the right woman”; if he were to marry the wrong type, “she couldn’t bear that.” And sure enough, when, sometime later, Edward marries the crass but licentious Pauline Silver, the troubles begin. In a series of increasingly comic episodes, the shade of Rosamund makes it impossible for Edward and Pauline to consummate their marriage, going so far as to hop into bed with them herself! A light and charming tale with a wonderful conclusion, this story comes as a breath of fresh air after the heaviness of the decidedly outré “The Flaw in the Crystal.”

“If the Dead Knew” introduces us to kindly pianist and music teacher Wilfrid Hollyer, who desires to marry one of his students, Effie Carroll. But Wilfrid would not be able to support her, and indeed is currently living with and dependent on his beloved and fairly well-off mother. When his mother sickens and is laying on her deathbed, the attending nurse instructs Wilfrid to pray for her, which he dutifully does; heartfelt prayers only slightly tinged with the wish that his mother would die, so that he might inherit and thus marry Effie. When the old woman does indeed succumb to her sickness, Wilfrid is quite understandably guilt ridden … especially when the ghost of Mrs. Hollyer comes back to stare at him, seemingly accusingly. Another ghost merely looking for affection, perhaps? In all, a sweet and moving story, up until that ambiguous final paragraph…

In “The Victim,” chauffeur Steven Acroyd cold-bloodedly murders his employer, Mr. Greathead, believing him to be standing in the way of marrying his sweetheart, the maid Dorsy Oldishaw. In what is easily this collection’s most gruesome sequence, Acroyd then hangs his victim upside down over a bathtub, drains all his blood, and chops the cadaver into sackable pieces. He has seemingly thought over every last detail, and as the weeks pass, it does indeed seem as if the chauffeur has gotten away with the perfect crime … until, that is, the ghost of Mr. Greathead begins to appear to him, in both broad daylight and at night! But this is no ghost out for vengeance; rather, it is one of the, uh, grateful dead, thankful for being released from his ailing body and wishing Acroyd no ill will whatsoever! Remarkably, this is a tale in which a murderer is not made to pay a horrendous price for his crime; a practically unprecedented development!

“The Finding of the Absolute” was another tale that greatly surprised this reader. Here, a metaphysicist named Mr. Spalding is devastated when his wife, Elizabeth, runs off with the Imagist poet Paul Jeffreson, a drunken, drug-abusing person of few morals. Spalding’s belief system is upended; his faith in eternal Justice negated. When he ultimately dies and goes to Heaven, Elizabeth and Jeffreson show him around, and even teach him how to create things with his mind and reach out to other heavenly dwellers. Spalding seeks out an audience with his hero, Immanuel Kant, and for the rest of the story the two discuss matters touching on consciousness, three-dimensional time, good and evil, and so on, enabling Spalding to see, in another hallucinogenic sequence, all of space/time at once. And it is a testament to Sinclair’s great skills as a writer that she makes it all surprisingly fascinating and accessible, even to a philosophy dunce such as myself.

This collection concludes with one of its eeriest and most atmospheric tales, “The Intercessor.” Here, Garvin, an estate agent/historian/antiquarian, desirous of a quiet place in the country where he can concentrate on his work, rents a room at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Falshaw, a gloomy couple that is expecting a baby. Garvin feels that something is not quite right with the couple and with the house, a hunch that grows stronger when he begins to hear the whimpering of a child every night. Eventually, Garvin does a little exploring, and actually sees the crying child: the ghost of a young girl who then crawls into his bed for comfort! The mystery of the Falshaws and the history of this ghost child make for gripping reading, and the story’s culmination is both tragic and sweet at the same time. A bravura piece of work, really, to cap this highly interesting bunch of stories, and another object lesson on why you should never withhold affection from those you care about … unless, that is, you want those poor wretches to come seeking that love and affection as mournful spirits…

So there you have it … eight finely crafted tales by a woman whose work was decades ahead of her time. May Sinclair is an author whose renown has dwindled to near extinction since her heyday in the 1920s, but thanks to this fine edition of Uncanny Stories from Wordworth, she may just possibly be finding some new appreciators today. Okay, then; with this minireview, I believe that I have shown Ms. Sinclair some well-deserved love and affection. Perhaps now her ghost will not be coming around to my apartment tonight…

I was reading along with no trouble suspending disbelief until I got to "internet influencers!" And then I thought, "Well,…

I recently stumbled upon the topic of hard science fiction novels, by reading a comment somewhere referring to Greg Egan's…

This story, possibly altered who I would become and showed me that my imagination wasn't a burden. I think i…

I have been bombarded by ads for this lately, just in the last week. Now I feel like I've seen…

Hi Grace, I'm the director of the behavioral neuroscience program at the University of North Florida, so I teach and…