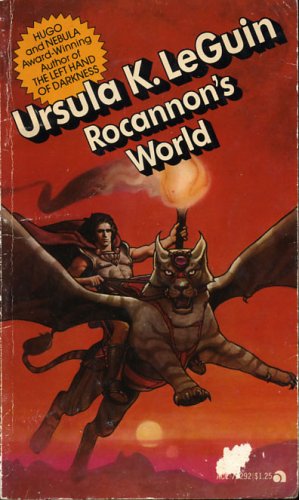

![]() Rocannon’s World by Ursula K. Le Guin

Rocannon’s World by Ursula K. Le Guin

Rocannon’s World, published in 1966, is Ursula Le Guin’s debut novel and the first in her HAINISH CYCLE. The story describes how Rocannon, an ethnographer, became stranded on the planet he was charting when a spaceship from Faraday, a rogue planet that is an enemy to the League of All Worlds, blew up his spaceship and the rest of his crew. Rocannon thinks he’s trapped forever until he sees a helicopter and realizes that Faraday must have a secret base on the planet. If he can find it, he can use its ansible to communicate with the League, not only letting them know that he lives, but also the location of the secret enemy base. (Fun Fact: This is the book that one of Orson Scott Card’s characters in Ender’s Game refers to when he mentions that the word “ansible” came out of an old book. Card enjoys playing this little game with SFF fans. I read Rocannon’s World after I read Ender’s Game, so this was an “ah-ha!” moment for me.)

So Rocannon collects a small group of companions and sets out across the planet on a quest to find the enemy base. Along the way he meets a few different cultures, some who are typical residents of high fantasy literature — castle-dwelling lords of a feudal society; the Fiia, who are like elves; the underground Clay People, who are like dwarves, etc. He tries to document information about these species and cultures as he goes (as usual, Le Guin’s anthropological interests are clear), but the difficulty of his quest interferes. He suffers much loss and tragedy along the way. Will he find the enemy base? Will he be rescued, or will he live on this planet forever? What Rocannon gets out of his mission is not something he expected.

Rocannon’s World has elements of both science fiction and fantasy — a technologically advanced star-traveler visits and charts the unknown species on a backward planet. The episodic plot, which sort of jumps from one cultural experience to the next, is entertaining, but not always compelling or believable. All these different HILFs (Highly Intelligent Life Forms) on one small planet, isolated from each other with no apparent cooperation or competition? Hard to believe.

Le Guin’s signature epigrammatic style is on display in Rocannon’s World, but her creativity and deep character development isn’t up to the level we’ll see later in her career. For example, I was disappointed to discover that this unknown planet was inhabited mostly by races who are recognizable from Earth’s history or mythology.

The prologue to Rocannon’s World is the short story “Semley’s Necklace,” which was published in 1964 in Amazing Stories. It tells of a young queen named Semley who met Rocannon when she went to the Clay People to ask them to help her claim a sapphire necklace that was her inheritance. They take her on a spaceship to retrieve the jewels and when she returns home with the necklace she gets an unpleasant lesson in space-time relativity. I liked this story, especially the intermingling of science fiction and fantasy, and I liked how this carried over to Rocannon’s story — he was also personally affected by the effects of space-time relativity.

Rocannon’s World is not up to Le Guin’s later level, but it’s enjoyable enough and a worthy read just because of its historical value as Le Guin’s debut novel. I listened to Stefan Rudnicki narrate Blackstone Audio’s version which is five hours long. Rudnicki was very good, as always.

~Kat Hooper

![]() In her debut novel Rocannon’s World (1966), Ursula K. Le Guin blends mythic fantasy and science fiction in this appealing, if not notably original, novel. The prologue, “The Necklace,” takes place many years before the main part of the story. Semley, dark-skinned and yellow-haired like all of her people on a remote, unnamed planet (called Formalhaut II by Hainish scientists from the League of All Worlds) is a queen of her people. She and her beloved husband are poverty-stricken, but Semley remembers that once her family owned a fabulous necklace that was stolen in her great-grandmother’s day. Finding it again becomes a passion for Semley, so she leaves one night to find her lost inheritance. Her travels will take her farther than she could have imagined. As Kat mentions, “The Necklace” was originally published as a stand-alone short story, an imaginative retelling of the myth of Freya’s necklace Brísingamen, and how her obsession with it ultimately brings her great sorrow.

In her debut novel Rocannon’s World (1966), Ursula K. Le Guin blends mythic fantasy and science fiction in this appealing, if not notably original, novel. The prologue, “The Necklace,” takes place many years before the main part of the story. Semley, dark-skinned and yellow-haired like all of her people on a remote, unnamed planet (called Formalhaut II by Hainish scientists from the League of All Worlds) is a queen of her people. She and her beloved husband are poverty-stricken, but Semley remembers that once her family owned a fabulous necklace that was stolen in her great-grandmother’s day. Finding it again becomes a passion for Semley, so she leaves one night to find her lost inheritance. Her travels will take her farther than she could have imagined. As Kat mentions, “The Necklace” was originally published as a stand-alone short story, an imaginative retelling of the myth of Freya’s necklace Brísingamen, and how her obsession with it ultimately brings her great sorrow.

In her travels, Semley met a Hainish scientist, Gaverel Rocannon, who never forgets Semley. Rocannon later travels to her planet as part of a scientific team doing cultural exploration. As the main part of this novel begins, Rocannon’s colleagues and their spaceship are blown up by galactic rebels, leaving Rocannon stranded and alone with the natives of the planet. He has no way to contact galactic authorities to warn them of the danger from these rebels, who are using this world as a secret base for their aggressive war of conquest. Rocannon determines that he needs to make the difficult journey to the rebel base, infiltrate it, and use their ansible ― an instant FTL communication device ― to send out a warning.

He and several helpful natives embark on a dangerous cross-country (and sea and mountain) trek, and Rocannon learns things about this unnamed world that he had never learned in his earlier scientific explorations. There are several different humanoid races on this planet, as well as flying windsteeds (an unlikely cross between Pegasus and a tiger) that are vital to the success of the mission.

Rocannon’s World is a little old-fashioned and derivative, vaguely Tolkienesque, with native races that are reminiscent of the elves, dwarves, and men, and including what Le Guin herself called “fragments of Norse mythology.” Not all of the science in it is believable; I had major issues swallowing the windsteeds that could carry not one but two men, as a practical matter. Le Guin also admits, in an afterword published in the 1970s, that Rocannon’s “impermasuit,” a near-invisible suit that protects against cold, heat, radioactivity, swordstrokes, and bullets (of moderate velocity) would suffocate the wearer in minutes.

But Rocannon’s World also has a reasonably solid plot, with an engaging interplay of science fiction and mythic fantasy, and there are flashes of brilliance in her writing. While Rocannon’s journey has more of a fantasy vibe to it, there are also occasional quotes from League handbooks and handy pocket guides that strengthen the SF element. Like Kat, my imagination was captured by the origin of the ansible in this novel, a concept so useful that it has been adopted not only by Orson Scott Card but many other SF authors.

Rocannon’s World will probably be of interest primarily to Le Guin completists and readers who love retro science fiction, but I don’t regret the time I spent in this world. This novel and Le Guin’s afterword are part of the impressive two-volume set Ursula K. Le Guin: The Hainish Novels and Stories, which will be published September 5, 2017. I’m gradually working my way through that collection.

~Tadiana Jones

The Hainish Cycle — (1966-2000) From Wikipedia: The Hainish Cycle consists of a number of science fiction novels and stories by Ursula K. Le Guin. It is set in an alternate history/future history in which civilizations of human beings on a number of nearby stars, including Terra (Earth), are contacting each other for the first time and establishing diplomatic relations, setting up a confederacy under the guidance of the oldest of the human worlds, peaceful Hain. In this history, human beings did not evolve on Earth but were the result of interstellar colonies planted by Hain long ago, which was followed by a long period when interstellar travel ceased. Some of the races have new genetic traits, a result of ancient Hainish experiments in genetic engineering, including a people who can dream while awake, and a world of androgynous people who only come into active sexuality once a month, and can choose their gender. In keeping with Le Guin’s soft science fiction style, the setting is used primarily to explore anthropological and sociological ideas. The Hainish novels The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed have won literary awards, as have the novella The Word for World Is Forest and the short story The Day Before the Revolution. Le Guin herself has discounted the idea of a “Hainish Cycle”, writing on her website that “The thing is, they aren’t a cycle or a saga. They do not form a coherent history. There are some clear connections among them, yes, but also some extremely murky ones.”

Thanks, Kat! Always nice to see the beginnings of a writer’s journey. I remember reading Semley’s Necklace in a story collection somewhere.

I loved the ending to Semley’s Necklace! I kept thinking “her quest is too easy, this is pathetic”, but then the ending….

I loved the ending to Semley’s Necklace! I kept thinking “her quest is too easy, this is pathetic”, but then the ending….

Le Guin is one of my all time favorites and I’m reading through her EARTHSEA CYCLE now. It’s a little disheartening to hear her imagination wasn’t as well displayed as it is later, but that’s proof she grew as a writer! It’s so cool this is the series referenced in ENDER’S GAME and admitting the impermasuit “would suffocate the wearer in minutes” has got to be one of the funniest confession I’ve seen an author make, LOL.

Elisabeth, if you’re a fan, I think you should read this anyway. It’s really interesting to watch how a favorite writer develops. It’s still an entertaining story!

I agree about the suit. That’s funny. :)

Looks like my TBR list just grew again!

I just finished The Left Hand of Darkness last night, the fourth Le Guin Hainish novel in this collection that I’ve been reading the last week or so (reviews pending). It’s been fascinating reading these novels in order. Well worth the time!