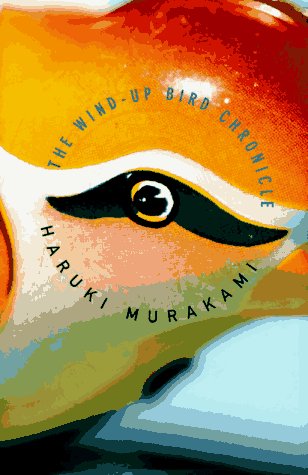

![]() The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle by Haruki Murakami

At first glance, Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle is about Toru Okada, a legal assistant who has given up his job in the hope of finding a more fulfilling purpose. Though happily married, his cat, Noboru Wataya, has gone missing. If a missing cat sounds too straightforward for a novel often described as the masterpiece of a man who is often mentioned as a dark horse to win the Nobel Prize for Literature, well, there’s a lot to unpack in this summary. Also, Toru is about to learn that his brother-in-law defiles women and his own marriage with Kumiko is in serious trouble.

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle can be interpreted along several lines, but perhaps our struggle to form meaningful relationships built on common understanding is the first way into this novel. The story begins with a phone call. Toru is cooking spaghetti when he picks up the phone and a woman asks for ten minutes of his time so that they can talk long enough to truly understand each other. Such an understanding between two people might be unlikely even after hours on the phone — especially since we barely seem to understand ourselves. Kumiko will eventually leave Toru, worrying that he does not understand her and fearing that she does not understand herself. Toru, meanwhile, will at one point explain that he is “just trying to untangle the simplest complication in my life,” but he finds even the simplest knots remarkably difficult to solve. Life becomes even more difficult because, like many of Murakami’s novels, this one exists on more than one plane. Toru begins to encounter people in his dreams, but his interactions there have consequences in the waking world. Who is he if he exists on a plane that he never knew existed?

The novel might also be read as an existential commentary. Toru does not know what he wants to do with his life, and he meets many people as he attempts to figure out what is happening to him. Sadly, many of the people he meets are just as confused and disoriented as he is. May Kasahara, for example, does not want to follow the same path as everyone else. She has dropped out of school and tries making it in a wig factory. Lieutenant Mamiya, meanwhile, is a veteran of the Japanese invasion of Manchuria. But at the end of his experiences, he is left incomplete. He tells Toru that:

Whenever I see a well, I can’t help looking in. And if it turns out to be a dry well, I feel the urge to climb down inside. I probably continue to hope that I will encounter something down there, that if I go down inside and simply wait, it will be possible for me to encounter a certain something. Not that I expect it to restore my life to me. No, I am far too old to hope for such things. What I hope to find is the meaning of the life that I have lost. By what was it taken away from me, and why?

Toru also begins to climb into wells. If we look deeply into ourselves, free from distraction or temptation, will we like what we find? It is interesting to think that a deeper self might exist, but it is scary to consider that others can tamper with this deeper self. As he progresses through his journey, Toru learns how to help people on that deeper level, and it is only when he begins to explore the side of himself that exists in dreams and wells that Toru is able to begin resolving his own conflicts.

Thematically complex and over six hundred pages long, The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle may intimidate some readers. Its structure can be just as daunting because although it seems like a journey, Toru’s story rarely feels linear — not even even “linear” in an episodic or non-linear way like Odysseus’s journey in The Odyssey. Toru meets people, often randomly, and their backstories are presented in parallel to his own. To be honest, at times I found my attention waning during these digressions and newspaper articles and letters and backstories. People are difficult to understand, and though it makes sense that this text would illustrate that theme by introducing Toru to other characters, it is still demanding to meet so many people over the course of a narrative.

The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, translated into English in 1997 by Jay Rubin, has more than once been described to me as Murakami’s masterpiece. There’s a case to be made against this claim. For one thing, just as many people have told me that Kafka on the Shore, translated into English in 2005 by Philip Gabriel, is the better novel. Furthermore, while, yes, I did enjoy this novel, I also finished several other books while reading it. And there’s this, too: there are scenes and characters in this novel that I expect will stay with me for years to come, particularly Toru’s time in the well, the bird whose cry winds up the day each morning, and Noboru the lost cat with a bent tail. And yet, these are not the most powerful moments I’ve encountered in Murakami’s fiction. Though it’s possible this novel is overrated, the masterpiece conversation is definitely a distraction. After all, haven’t we all read books that are not masterpieces without regret?

Ultimately, I liked The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle. Its ending surprised me and in its best moments, it created an atmosphere that drew me in completely. Recommended.

I haven’t read any of Murakami’s work yet (much to my chagrin), and I’m unsure where to start. Since you’ve read and enjoyed so many of his novels, Ryan, could you make a recommendation? Thanks!

After Dark is viewed as OK by people that read him from the start but it was my first book by him and I thought it was great. Start there.

Thank you! :D

Yet another great Murakami review that makes me feel like I need to branch out beyond my normal genre confines and tackle more literary books like his works, especially given my lifelong connection to Japan. Ah, if only we had more time for all these books!

I loved his take on the Orpheus myth in this one. This is not my personal favorite of his but I do think it might be his masterwork.