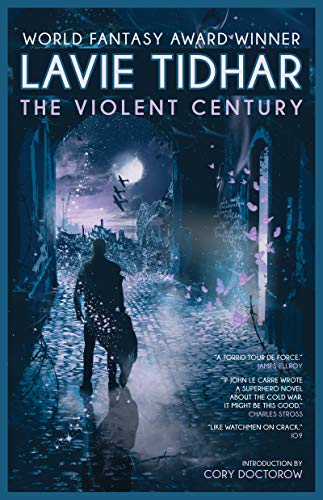

![]() The Violent Century by Lavie Tidhar

The Violent Century by Lavie Tidhar

Thanks to his two most recent novels, Central Station and Unholy Land, Lavie Tidhar has quickly become one of my favorite contemporary novelists, and so when I was given the opportunity to read a re-release of his earlier book, The Violent Century (2013), I leapt right on it. Clearly, the last two books were not evidence of some sudden leap upward in achievement, as The Violent Century stands side by side in craft, structure, and thoughtfulness.

The novel posits an alternate history where in the early 1930s, a “probability wave” (promulgated accidentally by a German scientist) courses through the world and changing everyone’s DNA. For most, the effect was either imperceptible or minor. But for a select few, the wave transformed them into Ubermensch (think your garden-variety super-powered folks). Given the timing of “The Change,” and the book’s title, the reader can be forgiven for assuming that one subject Tidhar is going to explore is the impact of superheroes on World War II (and then the century’s other wars, proxy wars, and police actions). And yes, superheroes from a host of countries (the US, Britain, Russia, Germany, Transylvania, etc.) take part in the war. But what surprises (and probably should not), is that History merely shrugs off the existence of superheroes as barely a blip. Yes, Jewish superheroes fight in the Warsaw Uprising. Yes, German and Russian superheroes battle in the sky over Stalingrad. But the Holocaust still happens. Auschwitz still opens. The people of Stalingrad still starve. The dead still litter the beaches of Normandy. Mengele still experiments. Useful Nazis like Von Braun are still given a pass into an America seeking its superpower cape, er, mantle. And then the Cold War still falls into place, America still sinks into the blood-thickened mire of Vietnam, the Russians do the same in the blood-tinted rocks of Afghanistan. Sure, one of the characters extends a pragmatic explanation that the superheroes merely balance each other out, but I’d argue Tidhar is making a more grim point than a basic algebra equation.

The story opens in present time, with two British superheroes, Fogg and Oblivion (their powers are manipulation of fog and disintegration, respectively) reunite after a long time apart, with Oblivion bringing in the recalcitrant Fogg for a de-briefing by The Old Man, head of the British superhero agency since the time of the Change (Ubermensch can die, but they do not age). From that point The Violent Century skips about in time between just before the Change and the present time, alighting at various key points: Fogg’s recruitment by The Old Man (OM: “I’m here to take you to a special school. For special people. People like you. Where you will be happy.” Fogg: “Really?” OM: “Of course not boy. Don’t be bloody stupid. I’m here to give you a job.”), the first time he and Oblivion met (the beginning of a long partnership and perhaps more), major and minor battles, assassination attempts, the Nuremberg Trials, the Berlin Wall, Vietnam, and more.

The narrative language, like the book’s structure, is often fragmentary, clipped, and taken together the two create a sense of dislocation and chaos while precluding any feeling of smooth progress. In other words, style and structure act as a perfect analog for the time period. As does Fogg’s name and power, and the underlying mystery of just why the Old Man has called him back in to go over yet again Fogg’s past reports, in particular those that deal with the German scientist who unintentionally initiated the Change and his young daughter. It’s clear to both the Old Man and the reader that Fogg has held something back about what really happened decades ago, but what that is remains appropriately enough enshrouded in mist for nearly the entire book, adding some suspense and creating a plot point that compels the reader forward.

That X-men reference cited in Fogg’s recruitment scene is only one example of the many Easter eggs for comic fans. There’s a visual of a classic superhero landing-pose, a classic reference text on the Ubermensch is written by a Stanley Lieber (Stan Lee’s real name) while Superman’s creators Shuster and Siegel make their own cameo appearances. At one point a character, tripping, sees:

a man in blue walks past wearing red underpants and a cape … He can see people’s thought hovering over their heads … A man climbs like a spider up a wall … He is bitten by a radioactive spider, falls into an acid vat … given a power ring … experimented on by military scientists … is bombarded by cosmic rays …

These add some welcome humor to The Violent Century, or if not humor some fond moments of recognition. But again, Tidhar is interested in more than making cute in-jokes. The Ubermensch, while recognizable obviously as analogues to our real-world (if one can use that word here) superheroes, are also delineated in ways to make points about those cultures they appeared in. American Ubermensch such as Tigerman and Whirlwind are classic caped crusaders, flashy and arrogantly self-confident and self-regarding (Tigerman “sweeps back his blond mane” and “throws back his mane of blond hair like he’s posing for the cameras”). German heroes take on the imagery and the personal architecture of the Third Reich. British Ubermensch like Fogg and Oblivion, reflecting Britain’s aging, waning empire in comparison to a young America on the rise, are held back as “observers” rather than as active participants (or at least, that’s the starting plan).

Even the Easter eggs themselves are transformed into serious explorations of theme, as when Schuster, on the stand, tells the prosecutor and the audience that:

Those of us who came out of that war, and before that, from pogroms and persecution and to the New World. To a different kind of persecution, perhaps. But also hope. Our dreams of heroes come from that I think. Our American heroes are the wish-fulfillment of immigrants, dazzled by the brashness and the color of this new world … We needed larger-than-life heroes, masked heroes to show us that they were the fantasy within each and every one of us. The Vomacht wave did not make them. It released them. Our shared hallucination, our faith. Our faith in heroes … We need heroes.

Our superheroes are created by individual artists, but they also are created and shaped by our collective selves, an extension not only of the writer/illustrator’s mind/hands but of an entire culture’s fears, flaws, dreams, and needs. Which makes it all the more grim when Lidhar bleakly melds pop culture with the searing trauma of 9/11:

It’s a bird! It’s a plane. No it’s —

It’s a plane. Hitting, as though in slow motion, the top of the north tower of the World Trade Center … We watch and rewatch in slow motion, in high-definition, the moment the dream dies.

All that time we had expected a savior. A man. A hero. But what’s a hero? Someone leaping from the color pages or from the silver screen, gun in hand, to rescue us. To make it stop. To disarm the hijackers …

It’s a bird. It’s a plane. No, it’s —

Nothing. No one.

That day we look up to the sky and see the death of heroes.

That question, “what is a hero,” is repeated again and again throughout the novel, haunting its pages and its entire length. Tidhar’s use, at times, of the plural narration (the “we” in the above example) directs that question right toward the reader, as well as making the reader complicit in its answer. Like the non-linear structure and the fragmented narrative style, it’s yet another wonderfully effective stylistic choice.

None of these stylistic devices, however, would work if the reader were not invested in the characters, in the emotionality of the work. Fogg gains our sympathy almost immediately, while Oblivion starts off as a bit of a cipher, but then, through his relationship with Fogg, becomes just as emotionally compelling a character. All of which makes for a powerful convergence of motivations and emotions at the end.

The Violent Century is a wonderfully constructed, crafted work that bears a great emotional weight even as it raises more intellectual questions. It’s the kind of work that lingers in the mind long after the reading and leaves the reader unsettled as they roll ideas over and over in their head. Just as good fiction should do.

This week, this review seems disturbingly timely.