![]() The Temple of Fire by Francis Henry Atkins (Frank Aubrey/Fred Ashley)

The Temple of Fire by Francis Henry Atkins (Frank Aubrey/Fred Ashley)

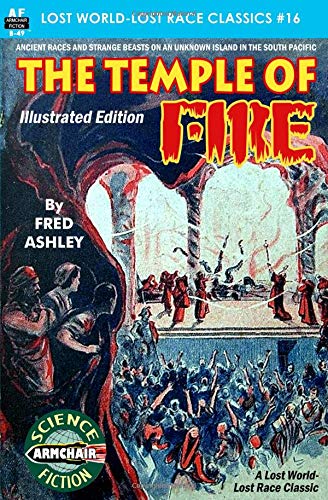

As I mentioned in my review of English author Francis Henry Atkins’ third novel, The King of the Dead (1903), this was a writer who chose to hide behind a number of sobriquets, all of which featured the initials “F.A.” Those pen names were Frank Aubrey (which he used for that 1903 novel), Frank Atkins, Fenton Ash and Fred Ashley. I had hugely enjoyed the third novel by this seldom-discussed author, so eagerly jumped at the chance to try my luck at another. Fortunately, Armchair Fiction’s current 24-volume Lost World/Lost Race series has now made another of this unjustly neglected writer’s works available, namely The Temple of Fire (1905), the author’s seventh novel out of an eventual 14. This book was originally released as a hardcover by the British publisher Isaac Pitman & Sons, sporting the Fred Ashley pseudonym on its front cover; Atkins was already 58 at the time of its publication. Twelve years later, the book saw its second incarnation as the February 1917 release from the Boys’ Friend Library, featuring charming illustrations throughout; artist, sadly, unknown. (I might add parenthetically that the Boys’ Friend Library reprinted popular novels, in paperback format, from the Boys’ Friend, a British “story paper” that featured short novels for younger readers, as well as other books deemed suitable for its target audience. Ultimately, 1,440 such paperbacks were released, The Temple of Fire being No. 366.) And after this, Ashley’s novel fell into complete obscurity for almost a century, until Armchair Fiction, God bless ‘em, chose to resurrect it in 2015. This latest release of the book happily includes all the illustrations from the 1917 reprint and proves to be still another winner from Mr. Atkins. But whereas the 1903 book had been very much an adult affair, this later book is decidedly for younger readers; what we would today call a “YA book.” More on this in a moment.

As I mentioned in my review of English author Francis Henry Atkins’ third novel, The King of the Dead (1903), this was a writer who chose to hide behind a number of sobriquets, all of which featured the initials “F.A.” Those pen names were Frank Aubrey (which he used for that 1903 novel), Frank Atkins, Fenton Ash and Fred Ashley. I had hugely enjoyed the third novel by this seldom-discussed author, so eagerly jumped at the chance to try my luck at another. Fortunately, Armchair Fiction’s current 24-volume Lost World/Lost Race series has now made another of this unjustly neglected writer’s works available, namely The Temple of Fire (1905), the author’s seventh novel out of an eventual 14. This book was originally released as a hardcover by the British publisher Isaac Pitman & Sons, sporting the Fred Ashley pseudonym on its front cover; Atkins was already 58 at the time of its publication. Twelve years later, the book saw its second incarnation as the February 1917 release from the Boys’ Friend Library, featuring charming illustrations throughout; artist, sadly, unknown. (I might add parenthetically that the Boys’ Friend Library reprinted popular novels, in paperback format, from the Boys’ Friend, a British “story paper” that featured short novels for younger readers, as well as other books deemed suitable for its target audience. Ultimately, 1,440 such paperbacks were released, The Temple of Fire being No. 366.) And after this, Ashley’s novel fell into complete obscurity for almost a century, until Armchair Fiction, God bless ‘em, chose to resurrect it in 2015. This latest release of the book happily includes all the illustrations from the 1917 reprint and proves to be still another winner from Mr. Atkins. But whereas the 1903 book had been very much an adult affair, this later book is decidedly for younger readers; what we would today call a “YA book.” More on this in a moment.

The book introduces us to a young British lad named Ray Lonsdale, the son of a millionaire father. While Lonsdale, Sr. is off hunting for gold in the interior of Australia, Ray has been left in the charge of family friend and gung-ho naturalist Dr. Strongfold, who has taken Ray on board the family’s steam yacht, the Kestrel, on an interesting quest. Strongfold had recently heard of a legendary race of web-footed, amphibious humanoids who supposedly lived on an island not terribly far off the New Guinea coast, and was dead set on finding them. Once near the supposed coordinates of said island, a well-nigh impenetrable morass of floating vegetation is discovered, with only one narrow lane permitting passage through its outer borders. But once inside this barrier, the crew of the Kestrel not only discovers the legendary amphibians — “Mecanoes,” as it turns out their name is — but also a lost civilization of stranded South Americans, probably Spanish descendants, who had colonized the island of Toraylia, at its center, hundreds of years before. A volcanic eruption had split Toraylia, many years earlier, the result being the depleted island of Toraylia, the smaller island of Cashia, as well as hundreds of tiny islands, all hidden from the world by the encircling, impenetrable, Sargasso-like sea growth around them.

Thus, the Kestrel’s skipper, Capt. Warren, and the rest of the seamen are stunned one night when they are attacked by the crew of a multi-oared galley, shooting arrows and hurling other primitive weapons at them. This ancient galley is no match for the yacht’s cannon and Maxim gun, however, and the battle is a brief one, during which one lad jumps into the water and swims to the Kestrel for his very life. This lad turns out to be Peter Newlyn, a British youth who’d been held in slavery, along with his younger brother, for the last two years, and who now has a very strange story to tell. It seems that the smaller island of Cashia had conquered all of Toraylia, and that its evil, red-robed priests were in the habit of sacrificing slaves to the monstrous cuttlefish creature that resided in the heart of the mountain fortress known as the Temple of Fire. Ray & Co. promise to help Peter rescue his younger brother, and are eventually befriended by the exiled Toraylian king Rulonda and his young son Loroyah, as well as those bizarre Mecanoes themselves. But can even these stalwart fighters prevail against the thousands of ill-intentioned Cashians arrayed against them?

Whereas Atkins’ earlier The King of the Dead novel had been geared for a more sophisticated audience, with adult — indeed, often overwritten — verbiage and detailed descriptions, The Temple of Fire is a more simply written affair. It avoids the 10-cent words that the author seemed to love showing off in the earlier book, and its manifold horrors are muted and toned down. Thus, although there any number of monstrous entities to be had here, the carnage that they inflict is never described in detail, and is often just mentioned in passing. The earlier book had depicted zombies biting the throats out of people in some detail, but here, the cuttlefish monster, the giant iguana, the flying skate fish, the blind albino lizard, and the man-eating, ambulatory (!) sea anemones all present dangerous threats to the boys only, and the violence that they dish out to others is not dwelt upon.

Reinforcing the notion that this is indeed a novel for younger readers is the fact that Ray, Peter and Loroyah are all energetic youths — in their early 20s, I would venture — who are often shown leading the older seamen in battle. Ray and Peter are each given their own launch — one electric, the other steam powered — to enter into naval engagements with the Cashians, and the book is entirely depicted from Ray’s point of view. As Ashley tells us in his intro, there is nothing here that would be “unsuitable for healthy, manly boys to read…” I might add that whereas The King of the Dead had boasted stilted, overly ripe and unnatural dialogue (that was yet a pleasure to read), this later book features dialogue that is completely naturalistic and credible, right down to the Cockney (?) accent that is characteristic of first mate Tom Waring.

In truth, one would never know that the two novels were penned by the same person, so vastly different is the style of writing between them; the same difference as that between, say, Philip K. Dick’s The Penultimate Truth and his kiddie novel Nick and the Glimmung. Similarities between the two books include a civilization that has been completely shut off from the rest of the world (the Brazilian kingdom of Myrvonia, in the earlier novel) and an exiled king who is plotting to regain his throne (in The King of the Dead, that was Manzoni, living in the Brazilian wilderness with his daughter Rhelma). And if that earlier novel was the more fully satisfying by dint of its pleasing detail and characters who were more fully realized, the latter yet manages to please, what with its unceasing action, likeable leading men, greater panoply of outlandish monstrosities, and wholly satisfactory denouement, in which each and every character gets precisely what he deserves. (And I do mean “he”; in this book for “manly boys,” there is not a single female character to be encountered!)

The novel, as has been inferred, contains any number of tremendous set pieces, including an early hunt for a humongous, iguana-like creature that resides in a pool at the bottom of a crater; the first battle with the Cashian galley; a protracted fight between the crew of the Kestrel, the Cashians and the Mecanoes, amongst a graveyard of abandoned, rotting ships; Ray and Peter’s first exploration of the lake to be found in the heart of an extinct volcano, replete with the aforementioned skate fish, albino lizard, flesh-eating sea anemones … and a hidden treasure lair; a tremendous battle that takes place on that same lake later on, between the boys in their launches and an armada of Cashian galleys; and finally, the infiltration of the titular Temple of Fire, replete with a face-off with that gigantic cuttlefish monster. So yes, never a dull moment, and all that. As Peter tells us early on, “You must be prepared for a bit of hard fighting … but, on the other hand, you will see many wonders…” And as Ray much later opines, “What a jolly lark … this is something like an adventure!” And few readers, I have a feeling, will disagree.

Of course, The Temple of Fire is hardly a perfect affair, and some seemingly inevitable stumbling blocks do crop up. For this reader, the lack of convincing detail was one of them, especially as regards geography. Thus, good luck trying to envision our heroes’ approach to the Temple of Fire, and that temple’s location vis-à-vis the city of Cashia itself. Ditto as regards the relative positions of all the islands and channels that the Kestrel visits, in that maze of impeding ocean matter. The reader’s imaginative powers are thus often sorely taxed, which, of course, is not necessarily a bad thing. Perhaps, in an effort to add credibility to his conceit, Atkins supplies the reader with notes at the book’s tail end, giving the facts pertaining to actual incidents involving web-footed amphibians in New Guinea, giant octopi and cuttlefish (most notably, the one that washed ashore at St. Augustine, Florida, in 1896), and flesh-eating sea anemones on the Channel Islands. And again, on the plus side, the author leaves his readers with one wonderful line that is both memorable and quote worthy: “A fight is never lost until it has been won!” Truly, words to live by!

Finally, one more piece of good news: Unlike the previous three books that I had read in Armchair Fiction’s Lost World/Lost Race series, this one contains a bare minimum of typographical errors, and was thus a double pleasure to read. I have high hopes that the next book I read in this wonderful series, Rex Stout’s Under the Andes (1914), will be similarly typo free. Stay tuned…

I love all the creatures!

And “Boys Friend” has an interesting history. I do wonder how many girls sneaked their brothers’ copies and read them under the covers, and I’m guessing it was a lot!

You’re probably right, Marion. Just LOOK at all these wonderful old covers…. http://www.friardale.co.uk/BFL/BFL.htm

Those are wonderful. And I’ve heard of the detective character Sexton Blake.

Me, too! Scund the Eternal is a new one on me, however! 😂