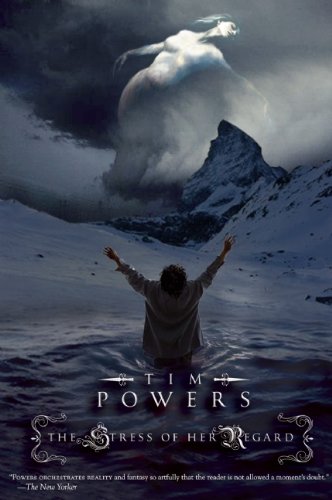

The Stress of Her Regard by Tim Powers

The Stress of Her Regard by Tim Powers

I thought I was sick unto death of vampire novels until I read this one. The Stress of Her Regard reminds me of Anne Rice at her best, some years ago, except with more action and less description of the carpeting.

The story centers around the nephelim, Lilith’s brood. Seductive, serpentine, and deadly, they are succubi and vampires, draining blood and vitality from their hosts even as they inspire them to creativity. One of these beings attaches itself to Byron and Shelley’s circle of expatriate poets, and the drama begins.

We see this through the eyes of gynecologist Michael Crawford, who gets drunk and puts his wedding ring on a statue’s hand at the bachelor party — and finds his wife murdered the morning after the wedding, in a scene reminiscent, probably intentionally, of Dr. Frankenstein’s wedding night. Suspected of the murder, he flees to the Continent, where he becomes Byron’s personal doctor. Traveling with the controversial lord, he will become entangled with poets, wannabe poets, fetishists who want to be vampire victims, and the mentally ill sister of his dead wife, who wants to see him dead. Along the way, he learns more about the creature to whom he is “married,” and tries to break his ties to it, as mysterious deaths begin to occur.

This is a creepy and atmospheric novel that I could not put down. I read at night until I couldn’t stay awake any longer, then got up and read in the morning. This is an enthralling novel of ancient evil, troubled love, birth, and death, which will stay with you.

~Kelly Lasiter

![]() Tim Powers published The Stress of her Regard in 1989. It was nominated for a world Fantasy Award in 1990. It did not win, but it won a Mythopoeic Award that same year. For many people, this is their favorite Tim Powers novel, and they describe it with words like “seductive” and “immersive.”

Tim Powers published The Stress of her Regard in 1989. It was nominated for a world Fantasy Award in 1990. It did not win, but it won a Mythopoeic Award that same year. For many people, this is their favorite Tim Powers novel, and they describe it with words like “seductive” and “immersive.”

I fully understand that I am in the minority here, but I didn’t like it.

There are several things to admire about this book. There are some things I liked. Then there are things I disliked, and finally, there is one thing I hated. I will try to cover my points in that order.

What I admired: The creation of the mysterious, attractive and deadly creatures who have fed on us throughout history is brilliant. If Powers gives them too many names; the lamia, “Lilith’s children,” succubae, muse, nephalim, and so on, it does reinforce the idea that they appear in every culture, in every language, because they exist side-by-side with us. They feed on us; but they also impart an amazing gift for poetry, and longevity, so some people seek them out. One of these is Lord Byron. Another is an old Austrian man who has had one of these creatures, in the form of a stone figurine, surgically implanted in his body. The stories of both these men are critical to the book.

Some people come to the attention of the nephalim in other ways and are considered “members of the family.” They are relatively unharmed, but the nephalim are jealous lovers. Human partners, lovers or children of the chosen one are soon killed or turned into vampires. This elaborate structure provides the plot twists and suspense in the book, which features Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and John Keats. Powers’s idea of a “secret history” of the famous Romantic poets is ambitious.

The main character of this book, though, isn’t Lord Byron. It’s a hapless English doctor, Michael Crawford, an obstetrician, who, drunk the night before his wedding, puts the ring intended for his wife on the finger of a marble statue that has appeared in the yard of the inn where the groom’s party is carousing. The next morning, Crawford staggers out to retrieve the ring, but there is no statue to be found. He has unwittingly “married” a lamia. His new bride Julia is brutally and mysteriously murdered on their wedding night. Crawford is untouched except for his ring finger, which has been cut off. Accused of Julia’s murder, Crawford flees to the continent, where in short order he discovers other suitors of the nephalim. He is taken up by Lord Byron, who is also under the sway of one of the creatures.

What I liked: In many places, the prose of this book is lovely. Powers did the research on the Romantics, and obviously studied daily life in the early 19th century. Byron is the most interesting character in the book, and Josephine, Crawford’s sister-in-law (Julia’s twin) is the second most interesting. I liked the section of the book that involved John Keats. The idea that the Carbonari, an Italian freedom-fighting group, were secretly vampire-hunters was a good twist. Another element that rings with supernatural dread is the appearance of the dead children of Shelley and Byron, turned to vampires by the nephalim, calling for their parents from out of the darkness. That is well done. I enjoyed the cameos by various historical figures including a much older French poet.

What I disliked: Michael Crawford. Crawford is mean-spirited and shallow most of the way through the book, achieving a certain level of heroism only in the last forty-five pages. Because I couldn’t care about him, the most common response I had to his travails was a sense of tedium. His callousness toward his sister-in-law, who follows him, motivated by vengeance, drags on way too long. Even when they have joined forces, Crawford forgets about Josephine for long stretches of time while he follows Lord Byron around like a puppy.

I think the “secret history” aspect of this story creates an awkward structure for the story. Powers is tied to what is documented in the lives of the poets, so the hand of the author, pushing the fictional characters to get them to show up in the right place at the right time, is obvious. The story leaps forward in time in ungainly strides. We get scene after scene with the famous poets and their wives/mistresses sitting about drinking or walking on the beach because nothing can happen until the next documented event. Also, there are places where the attempts to describe the creatures using early eighteenth century scientific language is either obscure, or unintentionally funny. At a dramatic point in the story, when Byron and Crawford have climbed to the top of a peak in the Swiss Alps, (because somehow this will free them from the attention of the nephalim), they find themselves in a state where time, matter and energy do not function normally. The air thickens until they can nearly swim in it. The scene is supposed to be terrifyingly dramatic, but I was laughing out loud at images of Bryon frog-kicking his way around the snowy air. It just didn’t work.

Also, for a “secret” history, it’s hard to find someone in the book who doesn’t know about the nephalim. They’re like UFOs for us; everyone has heard about them or knows someone who had a cousin who interacted with them, or something. So what’s the big secret?

The last fifty pages of the story, everything that has been dragged out in the first four hundred pages begins to gel, and we get a suspenseful scene with Crawford, Byron and Josephine working together. It’s a great moment.

What I hated: I tried to remember why I hadn’t finished this book back in 1993 when I first tried to read it. I read the prologue and it all came back to me. Mary Shelley. Mary Shelley is the only writer in the book who doesn’t have a nephalim lover. Presumably, then, any little thing she might have written, like a pamphlet or, I don’t know, Frankenstein, would be her own work, the achievement of her own imagination and artistic discipline, the result of her own agency. That’s not the case. Powers appropriates Frankenstein and bestows it on Percy first in the prologue, where Shelley tells about an encounter with the nephalim who claims him, and it’s a scene from the novel. Powers returns to Frankenstein later in the book and says this:

Shelley had even suggested the name of the protagonist, a German word meaning something like the stone whose travel-toll is paid in advance. She had wanted to use a more English sounding name, but it had seemed important to Shelley, so she had obediently called the protagonist Frankenstein.

The name choice story might be historically accurate; spouses often provide writers inspiration. But feminist, independent-thinking Mary Shelley “obediently” changed the character’s name.

She hoped the book would be published, but it already seemed to have fulfilled its main purpose, which was to draw out and dispel Shelley’s outlandish fears.

Throughout the book Mary is diminished even further, until she is literally just an unconscious body. This intentional dismissal of a woman artist does not advance the plot or the theme in any way. So why did Powers need to do it? I don’t know. I only know that in a book I already didn’t like, watching the author disrespect Mary Shelley did not change my opinion for the better.

So, I admire the ambition and the concept here, and I appreciate the fine prose. I didn’t care for the book and it was a struggle to finish it. Some books, we say, “aren’t for everyone,” and this one wasn’t for me.

~Marion Deeds

I love, love, love the new cover for this! The old one didn’t quite convey how delightfully creepy the book is.

Your comments about Frankenstein reminds me of the Barbie Mattel thing going on this week:

http://www.foxnews.com/tech/2014/11/20/mattel-apologizes-for-inept-computer-engineer-barbie/

Yes, I was reading about that.