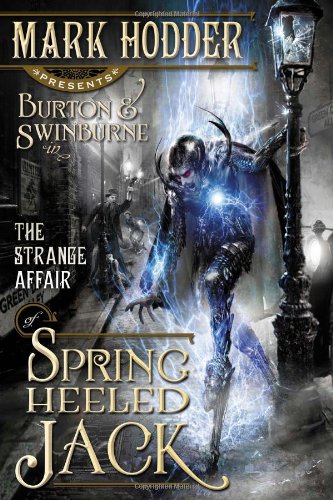

The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack by Mark Hodder

The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack by Mark Hodder

I’ve had some mixed success with the steampunk trend the past few years, thoroughly enjoying it when the authors pay as much attention to story and character as they do in coming up with new ways to mash-up old and new technologies, but finding it dully disappointing when the basic steampunk premise is the high point of creativity (Look! Airships flying over horse-drawn carriages while Dickens is walking through the streets!). Mark Hodder’s new book, The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack, I’m happy to say, does not disappoint, despite some awkward moments and a less-than-adequate ending.

Being steampunk, the novel is set in an alternate-history England during the late-1800s. However, this isn’t technically a “Victorian” Age as Queen Victoria was assassinated decades earlier (an act that the book returns to again and again, no matter that it took place so long ago). Socially and culturally, there are far larger changes, as the new English Empire finds itself at odds between two warring camps. In one camp are the Engineers/Eugenicists rapidly transforming England with their new machines (steam vehicles, ornithopters) and biological creations (dogs that deliver mail, birds that deliver messages). In the other camp are the Libertines, who oppose the technologists’ “destruction” of society and aim to form one based on beauty and art, and the Rakes, an offshoot of the Libertines who want to free themselves (and society) from all constraints, moral or otherwise.

Bounding about amidst all this rampant disorder is the veritable personification of chaos: Spring-Heeled Jack — a frightening creature of folklore who is reputed to appear suddenly out of nowhere, attack a young girl, and then disappear. And whom at least one policeman swears was present at the Queen’s assassination.

Stepping into this maelstrom is Richard Burton, the famed Victorian explorer, linguist, translator, and all-around bad-boy. At the start of Spring Heeled Jack he is newly commissioned by the Prime Minister to take on a new position: a sort-of freelance agent in the King’s service with the full power of the throne at his back. His several tasks include investigating Spring-Heeled Jack, the two warring social groups, as well as reports of strange disappearances and the possibility of werewolves. He is aided by the aforementioned policeman as well as his young friend, the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne.

The setting is more original than many I’ve come across in the genre, especially the Darwinists’ creations (the engineered ones are more predictably familiar), which add a nice sense of weirdness as well as humor due to the dismaying formula that for every good “tweak” the biologists make in a creature, there’s a bad tweak as well (the parrots’ flaw is particularly funny). One problem, though, is that the introduction of some of these elements can be noticeably clunky at times. Hodder does a good job of portraying the seedy side of London, especially during Burton’s trips into the poorer parts of town; we get a more honest sense of how much of the population lives, it seems to me, than we often do in these sort of novels.

Burton is an excellent choice as main character, since his actual life is so fascinating and replete with adventure that one needn’t fictionalize much to make him a compelling figure. He’s certainly the best part of the novel, though Swinburne makes a nice match, especially as he begins to come into his own as a character in the latter part of the story. Spring-Heeled Jack evolves nicely throughout the story until we finally start to get a handle on him a bit more than halfway through. He’s certainly one of the more original characters I’ve come across. Another strong secondary character is the highly literate head of the Chimney Sweep League, a mysteriously intriguing figure. The other characters aren’t as fully realized, and some are a bit one-dimensional. Burton’s fiancée for instance never really comes alive, and the policeman isn’t particularly memorable. A pair of government “fixers” have some rich potential that goes oddly unused. However, Burton’s personality and the quick moving plot mostly make up for such problems.

The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack moves toward a big showdown at the end, but the book also manages to bog down somewhat while doing so. One problem is we fall into a dreaded monologue sequence, which while interesting, slows things down while also feeling a bit forced (though Hodder, perhaps in recognition of this, does try to build in some rationalization for the scene).

We’re clearly set up for further books involving Burton and Swinburne as an investigative team. Despite some of this book’s awkward or clunky moments, and a somewhat disappointing close, I look forward to the next one. Recommended.

~Bill Capossere

![]() The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack was an unusual reading experience for me. It’s rare that I come away thinking that a book’s weaknesses exactly equaled its strengths, but that’s the case here. I also struggled to figure out what the tone and shape of the book reminded me of, and I’ve narrowed it down to two things; it’s either a prose version of graphic novels like Hellboy, or the Doctor Who universe. While many of us can get a visitor’s pass to a universe like the Doctor Who-verse, it’s really hard to move there and open a business, as Mark Hodder proves with this uneven but ultimately entertaining novel.

The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack was an unusual reading experience for me. It’s rare that I come away thinking that a book’s weaknesses exactly equaled its strengths, but that’s the case here. I also struggled to figure out what the tone and shape of the book reminded me of, and I’ve narrowed it down to two things; it’s either a prose version of graphic novels like Hellboy, or the Doctor Who universe. While many of us can get a visitor’s pass to a universe like the Doctor Who-verse, it’s really hard to move there and open a business, as Mark Hodder proves with this uneven but ultimately entertaining novel.

First of all, let me list the many things I like about The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack. Sir Richard Burton’s real-life 19th century exploits make him a fine match for this steampunk fantasy-adventure, and the pairing of Burton with poet Algernon Swinburne as a Holmes-and-Watsonish pair is brilliant. Burton is not only a man of action, but one of letters too, with a gift for languages, disguises and more arcane gifts such as mesmerism. (And you know who else lived in the house of his landlady/housekeeper? That’s right, Sherlock Holmes.) Most importantly, Hodder seems to enjoy writing Burton, and that keeps the book alive.

Swinburne barely escapes being a stereotype, but escape he does, and his character is valiant, intelligent, and innovative. Swinburne is better at drawing information out of people than Burton, and he volunteers for an undercover assignment that puts his life at risk. Burton’s musings about Swinburne’s motivations add a level of emotional suspense.

The alternate-history premise is original, and because of the time-travel element in the book, it’s deftly done. The book has a cabal of larger-than-life super-villains, which I think provides the graphic novel feel, and Hodder’s visuals in many parts of the book are awesome. Spring-Heeled Jack himself, with his stilts and the blue lightning wreathing his head, is breathtaking, and a later character, Mr. Belljar, works quite well too. Hodder’s pinnacle achievements of visual setting, for me, came with three locations in the book; Beetle’s chimney aerie; Darkening Towers, the crumbling mansion that serves as home-base for the Rakes, and especially the Battersea Power Station.

The steampunk premise works pretty well, although a few more details would have sold it better for me. If people really are soaring about London in rotor-powered armchairs, for example, where is the enterprising soul who sells earplugs to the passengers? Since genetically engineered swans pull box-kite carriers for humans, do all pedestrians carry extra-strength umbrellas? You know what pigeons can do to a car; think about swans.

Then there are the book’s weaknesses. Hodder’s writing and storytelling both suffer from disconcerting tics. For the first third of the book, every time a new invention appears on the page, the story judders to a halt while the author describes it in detail. The only saving grace is that he runs out of inventions eventually, and the pace picks up a bit until the jarring point-of-view shift in the second part, with a long explanation of what was really going on.

Hodder makes a misstep with the character of Isabel Arundell. This book does not need Arundell, but the writer gives us a passage in her point of view on Page One, thereby setting the expectation that she matters. Later, she is unceremoniously dumped out of the book. Later still, there is a discussion about her, as if she is important to Burton. In real life, Arundell was Burton’s wife and partner, a writer herself and a woman with strong opinions and contempt for convention. I think that Hodder may plan to bring her into later books in the series, perhaps as Burton’s adversary, but he handles her awkwardly here and it distracts from the story.

Hodder’s most distracting writing problem, though, is his habit of using synonyms for “said” at the end of lines of dialogue. Clearly, the now-dead J.I. Rodale, author of the The Said Book — it’s real, look it up — time traveled to our decade and put Hodder into a mesmeric trance, forcing him to substitute flashy words for “said.” The biggest victim of this is Swinburne. He trills, he shrills, he shrieks, he whines, he screeches. Other characters growl, snarl, reply, return and respond. They stutter, they yell, they cry. This is unnecessary. “Said” is a good soldier of a word that lets the reader focus on the dialogue itself. I invite Mr. Hodder to make its acquaintance.

Almost as distracting is the Star Trek dialogue from a climactic scene on the airship, with a red-shirt character in the cockpit saying, “I can’t do this on my own! She’s losing altitude!” (“I’m givin’ her all I’ve got, Captain!”). At the same time, another character yells, “She’s a nurse, not a bloody mechanic!” This is probably a deliberate wink to the fanboys, but it didn’t work for me.

How can these anachronisms and pop-culture references work in Doctor Who and not work here? Doctor Who has three decades of credibility; thirty years creating an irreverent and quirky fictional universe with its own rules. Hodder hasn’t earned my trust yet, so the references feel derivative, not clever.

Hodder does have an interesting vision, a good team of fictional inquiry agents, and enough skill to improve his storytelling and his writing if he chooses to. The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack is not a great book, but it is a good book, certainly worth reading. Ultimately, enjoyment edged out the flaws, and I will definitely check out The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man, the next book in this series.

~Marion Deeds

Burton & Swinburne — (2010-2016) Publisher: Sir Richard Francis Burton — explorer, linguist, scholar, and swordsman; his reputation tarnished; his career in tatters; his former partner missing and probably dead. Algernon Charles Swinburne — unsuccessful poet and follower of de Sade; for whom pain is pleasure, and brandy is ruin! They stand at a crossroads in their lives and are caught in the epicenter of an empire torn by conflicting forces: Engineers transform the landscape with bigger, faster, noisier, and dirtier technological wonders; Eugenicists develop specialist animals to provide unpaid labor; Libertines oppose repressive laws and demand a society based on beauty and creativity; while the Rakes push the boundaries of human behavior to the limits with magic, drugs, and anarchy. The two men are sucked into the perilous depths of this moral and ethical vacuum when Lord Palmerston commissions Burton to investigate assaults on young women committed by a weird apparition known as Spring Heeled Jack, and to find out why werewolves are terrorizing London’s East End. Their investigations lead them to one of the defining events of the age, and the terrifying possibility that the world they inhabit shouldn’t exist at all!

Trackbacks/Pingbacks