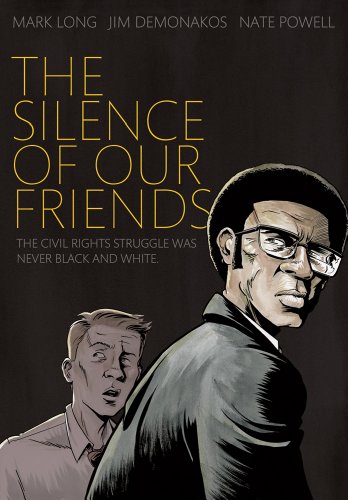

![]() The Silence of Our Friends by Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, Nate Powell

The Silence of Our Friends by Mark Long, Jim Demonakos, Nate Powell

One of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s most famous admonishments to all of us who lived in the Civil Rights era was that “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies… but the silence of our friends.” Mark Long’s graphic memoir, The Silence of Our Friends, reminds readers from that period, and surely opens eyes of those who were born long after the fiery 1960’s, that the loudest noise heard amidst the roaring flames of burning American cities, the rousing speeches of frustrated activists, and the staccato fire of automatic weapons echoing from the land of Viet Nam was the silence of too many good people. People who hoped that all this mess would somehow go away magically. People who stayed inside while others were being chased and beaten and firehosed on the streets outside their homes. People who thought Civil Rights only applied to “others.”

One of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr’s most famous admonishments to all of us who lived in the Civil Rights era was that “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies… but the silence of our friends.” Mark Long’s graphic memoir, The Silence of Our Friends, reminds readers from that period, and surely opens eyes of those who were born long after the fiery 1960’s, that the loudest noise heard amidst the roaring flames of burning American cities, the rousing speeches of frustrated activists, and the staccato fire of automatic weapons echoing from the land of Viet Nam was the silence of too many good people. People who hoped that all this mess would somehow go away magically. People who stayed inside while others were being chased and beaten and firehosed on the streets outside their homes. People who thought Civil Rights only applied to “others.”

Long’s memoir is set in Houston, Texas, in 1967, just after a student activist has been arrested for allegedly shooting a cop. Long’s father is a TV news reporter who drinks a little too much, his way of coping with the racism surrounding him in his office, his neighborhood, and worse, from the mouths of his own children who are increasingly being infected with this mainstream disease. Protests at historically Black Texas Southern University are reaching fever-pitch, and SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael is considering inviting the Black Panthers to join the protests.

Long’s father is befriended by another activist, Larry Thomas, who assures the other protesters that Long is a white man who can be trusted to report the facts objectively. Thomas is right, but this doesn’t mean that Long can be counted on to do the right thing always, to sacrifice himself for others, to speak out when he sees injustice.

But Long does take chances, inviting Larry and his wife and children to the Long home, in an all-white neighborhood. Though awkward at first, the two families bond over games of kick-the-can, the children’s feeling each other’s hair, and finally, everyone listening to that new Sam and Dave record, “Soul Man.” They part that evening as friends, but the friendship is sorely tested a few weeks later when, after white drive-by harassment of black people minding their own business on Wheeler Avenue, aka “The Bottom,” Larry’s daughter is run down by a redneck driver. While the girl lives, the neighborhood decides to take to the streets. Enough is enough.

During the still nonviolent march, the police demonstrate their own frustrations, bringing riot gear, too many weapons, and in the ensuing chaos, a policeman, attempting to shoot out an apartment light, sees his bullet ricochet and kill another policeman. Five students are arrested and charged with murder. But Long knows the truth. Now, will he speak out, and if he does, will anyone listen? And, when he sees his friend Larry beaten by police, will he do anything to stop it?

The story is told mainly from a child’s view, but this view is never immature or “childish.” Mark takes us through innocent childhood games of playing “Soldier,” a game that has tragic implications when set against the TV backdrop of live footage of an American GI executing a suspected Viet Cong terrorist. Mark and his friends also indulge in a game they call “Nigger knockin,” ringing the doorbells of neighbors and then hiding in the shrubs out of sight. It’s all so innocent; they don’t realize what they’re doing. But of course, we do. Many of us did the same in that time and place.

And one more thing about silence, a thing that might go unnoticed in this subtle but crisp black and white graphic narrative where we’re reminded through parallel framing of the awful similarity between the carnage in Viet Nam and that in our own American neighborhoods. Mark’s younger sister Julie is blind and attends a school for handicapped children where she plays “scissors, rock, paper” with another blind girl, teaches a deaf boy how to sound the words he reads, learns to spell her name in Braille, and then negotiates the winding corridors of her school so that she can announce her accomplishment to her principal.

Julie’s journey symbolizes the struggle of all the principal characters to rise above the indignities they have been born with or into. To state their names proudly, clearly for all to hear. To overcome the silence they were advised to keep if they wanted to fit in, to not cause trouble, to remain alive.

For silence may be golden, but friendship, human rights, and human dignity cannot be founded and maintained in a wordless vacuum. We need those words shouted into the night, or whispered in the quiet morning, even if we think no one can possibly hear.

FanLit thanks Terry Barr for this guest review.

I find myself genuinely inspired to seek out this text, not only from a standpoint of its readability, but for the poignant messages it apparently imparts. Thank you.

You’ve piqued my interest. While I often find graphic novels wanting, this story seems like the form could really run with it and enhance the impact. Thanks.

This has always looked like an intriguing book, and I think your review has tipped the balance. I will definitely track this one down.

Very informative review. I’m now prompted to check this one out. Thanks.

Yes, this looks really interesting. I look forward to reading more of your reviews, Terry!