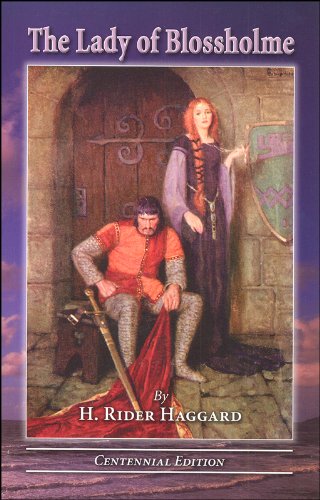

![]() The Lady of Blossholme by H. Rider Haggard

The Lady of Blossholme by H. Rider Haggard

The Lady of Blossholme was Henry Rider Haggard‘s 34th piece of fiction, out of an eventual 58 titles. It is a novel that he wrote (or, to be technically accurate, dictated) in the year 1907, although it would not see publication until the tail end of 1909, and is one of the author’s more straightforward historical adventures, with hardly any fantasy elements to speak of.

The story takes place in England during the reign of Henry VIII, in the year 1536. This was the period when King Henry was rebelling against Pope Clement VII, and when many Englishmen in the north, and many clergymen, were consequently rebelling against Henry, in the so-called Pilgrimage of Grace. To raise needed funds for this rebellion against the king, the Spanish abbot Clement Maldon murders Cicely Foterell’s father and tries to claim all the family’s lands and jewels. And what a hell this religious zealot puts poor Cicely through. She and her foster mother, Emlyn, are incarcerated in a nunnery and later tried as witches. Cicely’s husband is conked on the head and shipped overseas, and a murderous midwife is sent to do away with Cicely’s new baby. Before all can be put to rights, and our heroine and her husband are reunited, Cicely and her few friends must seek an audience with no less personages than Thomas Cromwell and King Henry themselves.

Anyway, that’s the story in a nutshell. But what a detailed, densely written, fast-moving and action-packed story it is! The Abbot Maldon — a holy man using evil methods to achieve his dubious ends — is one of Haggard’s more interesting villains, conflicted mess that he is. The character of King Henry here is revealed by Haggard to be a wise, brooding, decent, harried and coarsely jovial person, and Cromwell, too, avaricious as he may have been, is shown in a decent light. Unlike many of Haggard’s other historicals, this one, as mentioned, features hardly any fantasy elements, unless one can count Lady Cicely’s visions of angels, and Emlyn’s contacting of her swain, Thomas Bolle, by nighttime dreams, as fantasy.

Like several other Haggard novels that I’ve read recently, such as Swallow (1899) and Red Eve (1911), this book uses the plot device of newly married/engaged lovers forced to separate for long periods of time, and fighting near insuperable odds to reunite. And like those other titles, The Lady of Blossholme can serve as a fun history lesson for readers. I personally knew nothing of the Pilgrimage of Grace before opening this book, just as I knew little of the Great Trek before reading Swallow or the Battle of Crecy before getting into Red Eve. What an excellent way to acquire knowledge of a specific historical time and place! Haggard has really done his homework here, and his use of language and scenic description are extremely convincing. The average reader may require an UNabridged dictionary to assist with some words here and there (such as “gralloch,” “grieve,” “durance,” “pleasaunce,” “byre” and “wain”), but for the most part, Haggard, expert storyteller that he always was, keeps the reader flipping those pages. (I just read the cute litte Tauchnitz edition of this novel from 1909, as I still prefer to flip a page than click through an e-book!)

Although perhaps one of the more obscure titles in the Haggard canon, The Lady of Blossholme is well worth a reader’s time. With memorable characters, a unique setting, a different kind of Haggardian villain, several interesting Haggardian sidekicks, and a healthy dose of red-blooded action, the novel is a real pleaser. And, to top it all off, it concludes with one of the most satisfying final sentences ever. Don’t peep ahead! Just trust me on this one, okay?

Why did he dictate it? Was he losing his sight, or did he have arthritis or something? I’m very curious, and I know you’ll know.

This sounds like a book I would like because I am interested in that time period. The villain seems well-thought-out and plausible.

Marion, may I quote from Haggard’s autobiography, “The Days of My Life,” to answer your question? “When I returned from Mexico in 1891 I fell into very poor health. Everything, especially my indigestion, went wrong, so wrong that I began to think that my bones would never grow old. Amongst other inconveniences I found that I could no longer endure the continual stooping over a desk which is involved in the writing of books. It was therefore fortunate for me that about this time Miss Ida Hector, the eldest daughter of Mrs. Hector, better known as Mrs. Alexander, the novelist, became my secretary, and in that capacity, as in those of a very faithful friend and companion, to whose sound sense and literary judgment I am much indebted, has so remained to this day. From that time forward I have done a great deal of my work by means of dictation, which has greatly relieved its labour. Some people can dictate, and others cannot. Personally I have always found the method easy, provided that the dictatee, if I may coin a word, is patient and does not go too fast. I imagine, for instance, that it would be impossible to dictate a novel to a shorthand-writer. Also, if the person who took down the words irritated one in any way, it would be still more impossible. Provided circumstances are congenial, however, the plan has merits, since to many the mere physical labour of writing clogs the mind. So, at least, various producers of books seem to have found. Among them I recall Thackeray and Stevenson….”

So, just a general sense of frailty. He gives a good description of the process (and possible pitfalls), doesn’t he?

And yet, he managed to live on another 34 years and get a LOT of great work done in that time….

Okay. I’m convinced. I will download and read it based on your review. I enjoy factual English history through the Tudors, so this should be right up my alley! Thanks.

Hope you enjoy it, Jean. I would also recommend “Red Eve” to your attention, too. It is another terrific Haggard historical from the period you enjoy, and with even more fantasy content than this one….