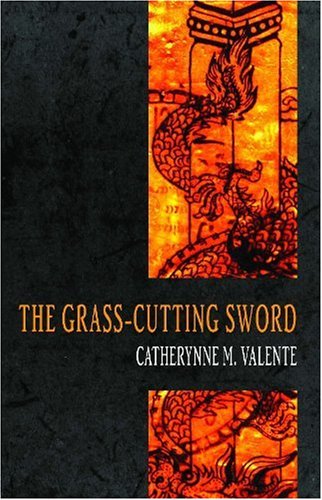

The Grass-Cutting Sword by Catherynne M. Valente

The Grass-Cutting Sword by Catherynne M. Valente

The Grass-Cutting Sword is a metaphor, comprised almost entirely of exquisite imagery, and every single word has obviously been chosen with a poet’s eye for sound and sight. It is a creation myth and a Grendel for the nuclear age, a story of beginnings and endings, of beauty and hideousness. The images Catherynne M. Valente chooses in The Grass-Cutting Sword will haunt your nightmares and inform your dreams. Close your eyes, for instance, and envision the monster of the tale from this excerpt of its self-description:

I am Eight. We are Eight. Lying on my side, if you prefer the symbolism. Eight heads, eight tails, eight snakes susurring against each other like auto-asphyxiating lovers, joined at the torso — circus grotesque, unseparated octuplets in a jar of formaldehyde, jumbled trunk a snaggletoothed muscle with the brawn of a circus strongman, and all the bells ringing, ringing in the gloam. Eight-all-together rattle eight diamond heads, heavy and flat, a clutch of serpent-castanets, and oh, the music I-and-we make, music for the maidens, music for the midden we made of our caves, music for the bones, the old rolled bones, rooster bones and buffalo bones and fox bones and tigress bones, bones like bellows and bones like cudgels, bones like whistles and bones like pillows.

Not a creature you’d like to come across on a dark night. Not even a creature you’d like to confront on the brightest day, armed to the teeth.

The Grass-Cutting Sword is a retelling of the Japanese creation myth, beginning with Izanami and Izanagicoming from nothing and procreating to produce the earth and all of its lands. While creation is a violent act, it proceeds apace until Izanami gives birth to fire and burned to cinders, ultimately transformed into the underearth itself. Izanami, not content with creation as it stands, follows after his sister/wife, and she nearly suffocates him with dirt, fungi, the detritus of the earth-beneath-the-earth. Izanami survives, and gives birth to three children when he cleans the dirt, flesh and blood from himself upon returning to the world: Ama-Terasu, the sun, Tsuki-Yomi, the moon, and Susanoo-no-Mikoto, the god of the sea and storms. While the sun and the moon come from Izanami’s eyes, Susanoo is hawked from his father’s nose, like snot, and he feels this insult deeply.

Susanoo is expelled from the heavenly realm and comes to earth in the form of a human after a quarrel with the sun. He alone of his mother’s children grieves for her, and he resolves to find her. When he arrives on earth, however, and is first adjusting to his human body, a mourning couple recognizes him and asks him to rescue their eighth daughter, Kushinada, “whose hair was dark as ink pooled in the belly of a crow, whose skin was pale as new-sewn silk!” She has been stolen by a beast with eight heads — a beast that has already swallowed their other seven daughters. The couple promises Kushinada to Susanoo as his wife if he can effect her rescue.

And so the tale is set in motion. The narrative is told in two parts: Susanoo’s tale of his history and his quest, and the tale of the sisters and the serpent. It seems that while the serpent swallows the sisters, it does more than digest them; it incorporates them, and it grows to be them. One is hard-pressed to wholly hate this monster, just as one may well find it difficult to feel much admiration for Susanoo as a hero, for the actions and emotions and thoughts of all are complex. The rescue of a fair maiden from the clutches of a monster is not as it seems. And soon we find we have traveled from the beginning of time to the ending of the first age of humanity; we have arrived at Hiroshima.

I did not expect this book to be what it is. I began to read it as if it were a story, like any I might expect to find in a standard anthology, a straightforward narrative. I quickly found that I could not read it that way. This book requires and rewards a concentrated, thoughtful reading, one that revels in every word, one that sees the colors and hears the sounds. Do not stint yourself on time when you read this beautiful book. Luxuriate in it. Wallow in it. Let yourself be lost in its glories. It is exquisite.

COMMENT Was I hinting that? I wasn't aware of it. But now that you mention it.... 🤔

So it sounds like you're hinting Fox may have had three or so different incomplete stories that he stitched together,…

It's hardly a private conversation, Becky. You're welcome to add your 2 cents anytime!

If the state of the arts puzzles you, and you wonder why so many novels are "retellings" and formulaic rework,…

I picked my copy up last week and I can't wait to finish my current book and get started! I…