![]() The Golden Fetich by Eden Phillpotts

The Golden Fetich by Eden Phillpotts

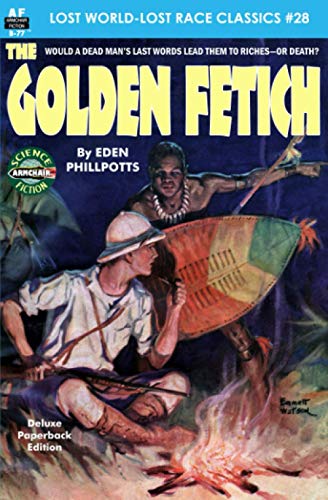

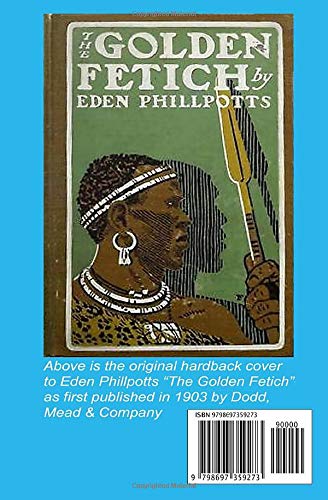

As I believe I have mentioned elsewhere, the influence that English author H. Rider Haggard had on his fellow writers was an enormous one. During his first 20 years as a novelist, Haggard came out with no fewer than 25 pieces of fiction, starting with 1884’s Dawn and up to 1903’s Pearl-Maiden. Of those 25, a good 14 were set in the Africa that Haggard knew so well, and of that number, around half could be set into that category that the author helped to popularize to such a marked degree: the lost world/lost race novel. His imitators were indeed legion, although very few that I have so far encountered came close to matching H. Rider’s skill in this department. One writer who I had never previously experienced, another Englishman with the curious name Eden Phillpotts, has recently impressed me, however, by how nicely he managed to pastiche Haggard’s inimitable style. The book in question is Phillpotts’ The Golden Fetich, which was originally released as a Dodd, Mead & Co. hardcover in 1903. The novel is one that I probably would never have heard of, were it not for Armchair Fiction’s ongoing series of semiobscure titles in its Lost World/Lost Race series, of which this one, released in Autumn 2020, is # 28. After its initial 1903 publication, as far as I can make out, The Golden Fetich only saw one reprint, a Tauchnitz edition in 1906, before going OOPs (out of prints) for over 100 years. Strangely enough, the book has seen three new editions since 2018, two of them facsimiles, and now, this reasonably priced Armchair edition.

Before I go on to discuss the merits of this very fine African adventure, a quick word about the author himself. Eden Phillpotts was born in India in 1862 and did not write his first novel until he was almost 30, after abortive careers as an insurance clerk and as an actor. After that first novel, 1891’s The End of a Life, Phillpotts would go on to write 126 (!) more, his last novel being There Was an Old Man (1959). In addition, he would, in his remarkably prolific career, come out with two dozen books of short stories, two dozen poetry books, 27 plays, and 14 books of nonfiction. He wrote in many genres — adventure, mysteries, even fantasy and sci-fi — but today is probably best remembered for his novels depicting life in his beloved Dartmoor. A close personal friend of Agatha Christie, Phillpotts was active till the very end of his long life, eventually passing away in 1960, at the age of 98.

Now, as for his 14th novel, The Golden Fetich: It introduces the reader to 30-year-old Roy Meldrum, a massively built, good-hearted if not terribly bright young man who, after his wealthy father’s recent passing, learns that his estate is actually fairly destitute, and that he has been left with a “mere” 10,000 pounds. After all his father’s belongings are auctioned away, Roy wanders about the empty abode with his cousin, the duplicitous Tracy Fain, and the two discover one item hanging on the wall that had previously gone unnoticed. It is a bundle wrapped in the skin of a lion, and inside it the men discover an amulet of gold with a curiously shaped figure on it, as well as a remarkable document. Written by an explorer of the African region populated by a tribe known as the Batoncas, this document gives rough directions to a fabulous hoard of jewels that the explorer had amassed before what he deemed to be his imminent demise! The cousins resolve on the spot to throw caution to the winds and spend Roy’s last 10,000 pounds in outfitting an expedition. Roy, it is decided, will keep the amulet, and Tracy the document. But Tracy, greedy little weasel that he is, notices some further directions as to the treasure’s precise location on the reverse side of this writing, and tears away those words, for his own private use.

And so, after a harrowing sea voyage, the expedition begins. The cousins had been joined, incidentally, by the skinny, red-bearded Lord Winstone before leaving England, as experienced and tough an African big-game hunter as any reader has encountered since Haggard’s wonderful Allan Quatermain. While at sea, a catastrophic wreck had caused the captain’s niece, Elizabeth Ogilvie — with whom both cousins had fallen in love — to be completely orphaned, and so she is allowed to accompany the trio, as is Dan Hook, the ship’s boatswain from Plymouth. Thus, the quintet, accompanied by dozens of Zanzibari and Sudanese porters, makes the 1,000-mile, yearlong trek from Zanzibar and through what is today called Tanzania and Zambia, their final destination being a tributary of the Luapala River south of Lake Mweru. And once arrived at their destination in the land of the Batoncas, after numerous adventures and perils, their odyssey, as it turns out, has only properly begun…

Now, I’m not sure if Phillpotts ever had any firsthand experience with Africa, as had Haggard, but if not, the man surely did do his homework. The author throws in any number of pleasing details to give his adventure a patina of verisimilitude. Thus, we hear of the weapons that Winstone insists on bringing along: the Express rifles, the Winchester carbines, the 12-bore shotgun, and on and on. We learn of malwa, the barley beer that the natives are fond of. We read about the buphaga birds, which perch on the tops of rhinos and other large animals and can thus give a hunter a clue as to their prey’s exact position. We are made aware of some of the habits of the larger animals in the area and get pleasing mentions of the abundant flora. Adding further realism to the conceit is the fact that just about all of the sites reached by Meldrum & Co. are findable with a good atlas, allowing the reader to follow the band’s progress quite closely. In truth, there is absolutely nothing in Phillpotts’ book that veers away from the realistic. This is a highly credible lost-race story, with none of the fantasy elements that Haggard employed so wonderfully. Thus, no centuries-old white queens, no witch doctors, no supernatural elements or use of magic, no reincarnation or prophecies. This is simply an African adventure story, done to a turn, convincingly set forth and written in a clean and forthright style.

Now, I’m not sure if Phillpotts ever had any firsthand experience with Africa, as had Haggard, but if not, the man surely did do his homework. The author throws in any number of pleasing details to give his adventure a patina of verisimilitude. Thus, we hear of the weapons that Winstone insists on bringing along: the Express rifles, the Winchester carbines, the 12-bore shotgun, and on and on. We learn of malwa, the barley beer that the natives are fond of. We read about the buphaga birds, which perch on the tops of rhinos and other large animals and can thus give a hunter a clue as to their prey’s exact position. We are made aware of some of the habits of the larger animals in the area and get pleasing mentions of the abundant flora. Adding further realism to the conceit is the fact that just about all of the sites reached by Meldrum & Co. are findable with a good atlas, allowing the reader to follow the band’s progress quite closely. In truth, there is absolutely nothing in Phillpotts’ book that veers away from the realistic. This is a highly credible lost-race story, with none of the fantasy elements that Haggard employed so wonderfully. Thus, no centuries-old white queens, no witch doctors, no supernatural elements or use of magic, no reincarnation or prophecies. This is simply an African adventure story, done to a turn, convincingly set forth and written in a clean and forthright style.

Phillpotts fills his story with a raft of exciting set pieces to keep the reader consistently bemused. Before our heroes even get to Africa, they must contend with a monstrous typhoon at sea — made all the more difficult by an opium-addicted ship’s captain — followed by a shipwrecking explosion. During their overland trek, they engage in a rhino hunt; explore the mystery of the Mapora tribe’s elephant spirit; take time out to pursue three of their retinue who had taken off with stolen supplies; do battle with a family of lions; get to know the peoples and leaders of three different tribes; follow in pursuit of Elizabeth after she is kidnapped; and become captives of the Massegi cannibals (who might as well be called the Meshuga cannibals!). And once arrived at their final destination, the land of the Batoncas, one of our heroes is forced to undergo a hideous ant torture, before Phillpotts treats us to a well-depicted battle scene between Meldrum’s crew and some 600 Batoncans on one side, and King Pomba and around 1,250 Batoncans on the other. Phillpotts adds some pleasing dollops of humor into the mix — the conversation between Dan Hook and the Maga-Migan King Unyah, with neither understanding the other at all, is simply hilarious — and throws in a few genuine surprises toward the book’s end that might strain some readers’ credulity, but that I found legitimate and set up neatly. At bottom, this is a hugely entertaining novel, and one that might even leave the reader with a tear in his/her eye, as Haggard himself was able to do on so many occasions.

Still, there are some minor problems to be had, foremost of which is the fact that Roy Meldrum, despite being the book’s protagonist, is just not all that interesting a character. As a matter of fact, he is kind of bland, if likeable, just as Tracy is bland and unlikeable, and Elizabeth is bland yet plucky. None of them are portrayed with anything approaching genuine depth. Thus, Lord Winstone easily steals the show here, being the story’s coolest, wisest and most experienced outdoorsman, with Dan Hook, the salty seaman, coming off second best. Phillpotts is guilty of an occasional ungrammatical sentence — such as “The stores and much ammunition was buried and concealed…” — and gives us some dialogue that comes across as distinctly unnatural. For example, here’s Elizabeth talking to Tracy on board the Morning Star while at sea:

…Look at all this glorious sapphire below us and turquoise above. See the fleecy clouds rippling over heaven, as the little foam caps ripple over the water; watch these great birds dropping like shooting-stars into the waves and the little furrow of foam. The air on my cheek and the sunshine on the sea make me thank a good God for letting me glory in these beautiful things…

Does that sound like natural dialogue to you? Anyway, these are merely quibbles, and despite these minor matters, The Golden Fetich remains a splendid read, and one of the finest pastiches of H. Rider Haggard — if that is indeed what it was intended to be — that I have come across yet. It is more than highly recommended.

As for me, as I mentioned up top, Phillpotts also wrote several books of science fiction, namely Saurus (1938), The Fall of the House of Heron (1948) and Address Unknown (1949) … all of which seem to be highly regarded. He also wrote a haunted-house novel entitled The Grey Room (1921). All four of those books are now exerting their siren call on me, so stay tuned…

I had to look up “fetich” because I was sure it wasn’t spelled correctly, but it is the archaic version of fetish.

Thanks for the review, Sandy!

Oh, my pleasure, Marion!