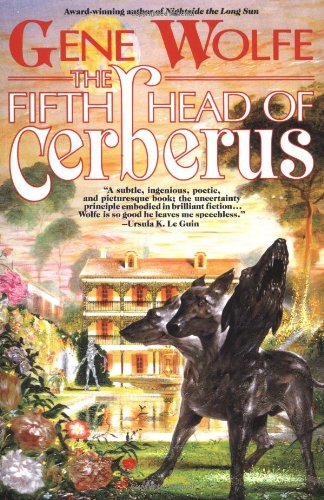

![]() The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe

The Fifth Head of Cerberus by Gene Wolfe

I don’t think I’m the only reader drawn to Gene Wolfe’s books — hoping to understand all the symbolism, subtleties, oblique details, unreliable narrators, and offstage events — and finding myself frustrated and confused, feeling like it’s my lack of sophistication and careful reading ability to blame. Wolfe is most famous for his amazing 4-volume THE BOOK OF THE NEW SUN dying earth masterpiece, which has a 1-volume coda called The Urth of the New Sun, along with two companion series, THE BOOK OF THE LONG SUN and THE BOOK OF THE SHORT SUN. Collectively they are known as THE SOLAR CYCLE, and these books tend to split readers into two camps: either dedicated Wolfe fans who find his works richer, deeper, and more subtle than anything else in the SF canon, or those who just don’t get it. I’m a great admirer of THE BOOK OF THE NEW SUN, which I have read twice through for the epic story and exquisite writing, but couldn’t even finish THE BOOK OF THE LONG SUN, which bored me into submission. But like a dedicated alpinist, I plan to try the ascent once again when the right conditions prevail, hoping to conquer the Everest of the genre someday.

The Fifth Head of Cerberus (1972) is Wolfe’s first book of substance (his first, Operation Ares in 1970, was not particularly good according to the author himself). It began as a novella, but he was asked to expand it to book length by adding two more linked novellas. So the book consists of three stories, each very different but tied together beneath the surface in tricky and oblique ways, a form of ‘literary kabuki,’ as Wolfe loves to create puzzles and drop little hints and revelations throughout his stories. Someone wisely observed that your understanding of a Gene Wolfe book only begins when you’ve read the last page. Once you get to the end, you feel compelled to go back to the beginning and search out all those hints that were seemingly irrelevant, and put together the hidden tapestry he has been carefully weaving. So if you are a fan of propulsive, easily-accessible stories with likeable characters and straightforward plots, this is the wrong book for you!

I’ll give a brief synopsis of the three novellas, but I won’t provide any spoilers for two simple reasons: 1) it would ruin your enjoyment, and 2) I’m not sure that I properly understood the underlying connections of the stories anyway. So I’ll just lay out the basic details, and if you are intrigued, then pick up the book and have a go at it yourself.

The Fifth Head of Cerberus

We are introduced to the twin worlds of Saint Croix and Saint Anne, which were originally colonized by French settlers but later were overtaken by later waves of colonists from Earth. There are stories that Saint Anne had an original race of aboriginals that were wiped out by the French colonists, but details are strangely vague. In fact, some claim that the initial race were shapeshifters, suggesting they may still remain, hidden in plain sight.

Our protagonist is a boy growing up in a mysterious villa with his brother David, raised under the watchful tutelage of Mr. Million, apparently a robot guardian who educates them. The boy and his brother initially are not cognizant of their father’s business, a high-end brothel, knowing only that there is a steady stream of wealthy visitors that come to their property to be entertained by a stable of attractive women. Their father is a distant and somewhat menacing presence who shows little interest in them until one day he invites them to his laboratory. He begins to give them a series of tests, more like experiments, which involve drugs, psychological tests, and leave them both drained and uncertain of their memories afterward. This continues for some time.

The boys eventually encounter a young girl who becomes their companion, get into some petty criminal activities together, and finally the boy is taken further into his father’s confidences. The details that are revealed cast the entire story into a different light, and the story takes a stranger turn as a mysterious anthropologist from Earth named John V. Marsh shows up, asking to speak with the author of the Veil Hypothesis, which suggests that the native aboriginals were never wiped out, but instead…

“A Story,” by John V. Marsch

This story is completely different in tone, more like a dreamquest of the aborigines on Saint Anne. It is told by John Sandwalker, who is seeking his twin separated at birth, John Eastwind. It is definitely one of the strangest and most hypnotic stories I have read, with a completely alien mindset and extremely unreliable narrator and details. Sandwalker encounters a woman and child at an oasis, then runs into the Shadow Children, creatures that may or may not be human, and may not even be corporeal at all times, since they seem to drift in and out of the real and dream worlds. The Shadow Children share their songs and food with Sandwalker, but are then captured along with him by the marshmen, who plan to sacrifice them to the river in order to carry their message to the stars. Are the Shadow Children the original inhabitants of Saint Anne, before human colonists arrived? Who, then, are the marshmen? Have they switched places, as was hinted at in Veil’s Hypothesis? The questions, conundrums, and mysteries pile up in this story, and Wolfe is not about to give any easy answers as he lets the reader fight to piece together the tidbits he scatters at whim. If this is his idea of a pleasurable reading experience, I found it a bit cruel and perverse, but apparently Wolfe fans can’t get enough of this.

V.R.T.

In the final story, Wolfe literally revels in misdirection, layers of narrative, the complete unreliability of the narrator’s memories, and the fragmentary nature of the source materials themselves. Although we are given more and more tantalizing clues as to the nature of the aborigines, what happened to the original French settlers, and what happened to the narrator of the first story, his father, and the anthropologist John V. Marsh, things get very tangled indeed.

Here we are presented with the scattered journal entries of John V. Marsh, who has been incarcerated by the authorities of Saint Croix under suspicion of being a secret agent and assassin sent from Saint Anne. His jailers do not believe his claims that he really is an anthropologist sent from Earth to learn about the fate of the aboriginals. We learn that he has spent several years on Saint Anne, trying to gather information on the aborigines, who supposedly still live in “the back of beyond,” essentially the outback. He also hears them referred to as The Free Folk of the hills, separate from the cannibal people of the marshmeres. He hires an old derelict named Trenchard who claims to be an aborigine himself, and his son V.R.T. as a half-aborigine, as guides to take him to the outback in the hopes of tracking down any surviving natives.

However, the framing narrative is of a mid-level inspector who is looking through the scattered documents pertaining to the prisoner Marsh, who must decide how to prosecute him. There is much doubt cast on his ‘cover’ story, although at no point does Marsh admit to being anything other than the anthropologist from Earth he claims to be, despite long bouts of interrogations, solitary confinement, and deprivation. His only means to communicate with other prisoners is through tapping on the walls in a code the prisoners have devised.

The journey Marsh describes in his journal entries (his jailers have provided him with pen, paper, and candle in the hopes he will reveal important information) is a strange one, somewhat reminiscent of the dreamquest of the second story, but the trip is mostly fruitless except for strange encounters with ghoul-bears and other predators, and growing suspicions by Marsh about the boy V.R.T. Eventually the tone of Marsh’s entries changes in a very subtle fashion, casting further doubts about his identity, but again nothing is spelled out. Oh, you are a cruel writer indeed, Mr. Wolfe! And yet the writing was skillful enough to keep me going, even with the growing suspicion that I would reach the end without any final answers. As it turns out, the story is so ambiguous that I don’t even know if it delivered any final clues that were just too subtle for me to grasp, or if he left it open to multiple interpretations, which I suspect is the case. In any case, don’t expect any spoon-feeding here.

The Fifth Head of Cerberus is not an easy read, and may not even provide the expected payoff for the hard work, but it remains a brilliant example of Wolfe’s impressive writing abilities, almost too clever for his own good. If you are a serious SF fan who likes challenging works, look no further.

Hah! You’ve nailed my issues with Gene Wolfe. I’ve got the first two volumes of the Book of the New Sun in a single volume called Shadow and Claw. I’ve still not read the whole thing. It’s fantastic writing and beautifully layered, but I get bored and abandon it every time I try to wade through it. The plot moves pretty slowly. Sigh – it’s probably time to give it another shot. I might have more patience for it now than I did 15 years ago when I bought it.

Wolfe’s plots are like icebergs. In any story, at least half if not more of what’s going on is happening under the surface.

Marion, I could certainly sense things happening beneath the surface. But to me, trying to read Gene Wolfe is like being stranded on an iceberg – cold, inhospitable, and daunting. I’ve started reading his “Best of Gene Wolfe” short story collection, and honestly I’ve been baffled by most of the stories so far, and haven’t enjoyed any of them. Is it just me, or are some other folks having the same reaction?

Tadiana, I think The Book of the New Sun is worth another try, but I had the exact same experience as you with The Book of the Short Sun. If it becomes a chore to try to wade through a book after multiple tries, that may mean it’s just not a good fit. I’m a bit jealous of Gene Wolfe fans who seem to ‘get it’, but at the same time I trust my own instincts. We read for pleasure, after all, so no use forcing the issue.