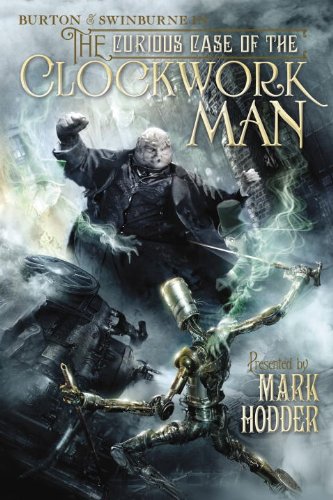

The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man by Mark Hodder

The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man by Mark Hodder

The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man is Mark Hodder’s second steampunk novel with Sir Richard Burton as the protagonist, following The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack. Though it is a sequel, and reading the first book will give you a fuller sense of setting and character, Clockwork Man stands pretty independently, so not having read the first certainly doesn’t preclude you from starting here. Unfortunately, while I mostly enjoyed Spring-Heeled Jack, The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man took a surprisingly large step backward in terms of reading enjoyment.

England of the 1860’s has been changed by the time-traveling events of Spring-Heeled Jack, turned upside down by new and accelerating technology, genetic modifications, and mystical powers such as clairvoyance and astral travel. With this as the background, Burton and his assistant, the poet Algernon Swinburne, end up involved with mythical diamonds that seem to lend strange powers to those who possess them, a returned-heir-who-may-not-be-who-he-says-he-is inheritance case, a sudden uprising of England’s lower classes, ghosts, zombies, flesh-eaters, a clockwork man, and possible threats from America, Prussia, and Russia.

If that sounds like a lot, well, it is. In fact, I’d say it’s too much. “Less is more” is a trite phrase, I know, but that it is a cliché doesn’t make it any less true. And here, I’m afraid, it should have been considered much more. There’s a line between “wildly inventive” and “messy,” and The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man feels messy. Rather than be satisfied with giving us a roller coaster ride of a story, it seemed Hodder wanted to give us the whole theme park. To be honest, the more that got tossed in, the less I felt interested, so that by the end I was skimming the last few chapters. Which is too bad, because there is a good story (or two or three) at the core.

The steampunk/alternative setting is generally strong, as it was in the first book, with lots of great new technologies and eugenic creations — such as huge insects used as modes of travel or a genetic modification gone horribly wrong that turns Ireland into a wasteland — to go along with alternate history moments such as England entering America’s Civil War on the side of the Confederacy. As with the plot, though, the setting would have been stronger had Hodder not served up quite so many ideas, so that we could linger over each idea and more fully enjoy it before the next came barreling through.

The main characters feel a bit more flat this time around. Some of that may have to do with the breakneck plot, and some with what felt like repetitive characterizations or actions (drunkenness, trance states, etc.), while the secondary characters are mostly two-dimensional. Herbert Spencer has some potential, but never really comes alive.

The pacing, as might be expected from the overstuffed plot, is hectic and uneven, often jolting from one scene to another. While doing so occasionally can be a nice technique to mirror what the characters are feeling, here it carries on throughout much of the book. The end feels like one fight scene after another and, as mentioned above, I lost much interest in what happened and started skimming to wrap up the basic plot questions. The big showdown with the villain is a bit anticlimactic and, as was one of the flaws with Spring-Heeled Jack, fell into the dreaded monologue mode. And you know an event is a bit forced when a villain has to announce “you realize of course that I have allowed your companion to approach merely to satisfy my curiosity.” It’s never good when a character has to rationalize acting stupidly.

I really wanted to enjoy this book, and I did for the first few chapters, but it went steadily downward from there for me. If I hadn’t known better, I would have guessed this had been Hoddard’s first work and not Spring-Heeled Jack, as it was so much more flawed in so many ways. We end with a third book clearly in the works, and based on how much I enjoyed Spring-Heeled Jack, I’ll certainly pick it up. But since The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man seems to stand enough on its own that it won’t be a must-read to continue on in the series, I can’t recommend it. And I hope book three recaptures the magic of the first one.

~Bill Capossere

![]() The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man has all the annoyances of its predecessor with less than half the fun.

The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man has all the annoyances of its predecessor with less than half the fun.

In Mark Hodder’s first Burton & Swinburne adventure, the novelty of his steampunk universe and the comic-book adventure sustained me, even though Mr. Hodder’s storytelling was awkward. All the writing and structural problems are still driving The Curious Case of Clockwork Man, exacerbated by a plot that accelerates past “implausible” and careers into “incomprehensible.”

Botanical disaster in Ireland! Theft of enigmatic “black” diamonds! Looming Prussian aggression! Fairies, mind control, mysterious asteroids; Britain’s involvement in the American Civil War; ghostly Rakes, almost-zombies… and I left out one or two. Buried under all this is an intriguing story, based on an historical case of a missing heir, a haunted house and an imposter come to claim the family fortune.

This part of the book, all too short, almost captures the feel of a steampunk Hound of the Baskervilles, with strange goings-on at a British country house. Unfortunately, soon this mystery is “solved,” with one of the less believable moments in the book, and we move back to London. The book’s pacing is strange, probably because Hodder is trying to juggle so many ideas. The book seems to come to an end twice, only to stagger on not unlike one of its almost-zombie characters.

The book has two villains, one who is identified about halfway through, although a medium informs Burton that this “puppeteer” is an unknowing puppet of another. Mediumistic powers make up a large part of the story, with the ghost of a sorceress haunting the country house, strange tapping heard at night and a piano that plays itself. The “front” villain has a power for which no foundation has been established, and while I was willing to accept astral projection, I was not able to believe this power when it manifested without warning. Later, Burton tries to explain this, but the reasoning just isn’t there. Along the same lines, the astral-projection knocks on walls in the house, trying to find a secret passage. If you can pass right through a wall, do you need to knock on it to determine if it is hollow?

The real scheme, however, involves the brainwashing of the workers of London by use of strange black diamonds. Soon the laborers are rioting, and then they develop a taste for human flesh. Meanwhile, the villain is forcing the Rakes to astral-project, and they develop a craving for “life,” which generally means tearing out living people’s vital organs. Hodder does stop short of having them shuffle and moan, “Brainnnsssss…,” but only just.

One of Hodder’s villains is two-dimensional. The other, the “front,” is, if it were possible, shallower than two-dimensional. They function in service to this haphazard plot, not out of any believable historical or fictional motivations of their own. In the case of the mastermind, this makes him not only unbelievable but frankly boring, an “evil” character from history acting evilly out of a love of… evil.

As with the first book, there are little beacons of brilliance; the tiny poet Swinburne crouched atop a giant dray-horse, holding a lance; the best use of a cookbook in a fight scene; or the note, B below middle C that sounds on the piano at the Tichborne house when no one is near it. The idea behind the “black diamonds” is a powerful one, as is this idea of knowing that you are somehow in the wrong timeline. I wish the book had explored those avenues more, and spent less time with ecto-plasmic zombies.

~Marion Deeds

Burton & Swinburne — (2010-2016) Publisher: Sir Richard Francis Burton — explorer, linguist, scholar, and swordsman; his reputation tarnished; his career in tatters; his former partner missing and probably dead. Algernon Charles Swinburne — unsuccessful poet and follower of de Sade; for whom pain is pleasure, and brandy is ruin! They stand at a crossroads in their lives and are caught in the epicenter of an empire torn by conflicting forces: Engineers transform the landscape with bigger, faster, noisier, and dirtier technological wonders; Eugenicists develop specialist animals to provide unpaid labor; Libertines oppose repressive laws and demand a society based on beauty and creativity; while the Rakes push the boundaries of human behavior to the limits with magic, drugs, and anarchy. The two men are sucked into the perilous depths of this moral and ethical vacuum when Lord Palmerston commissions Burton to investigate assaults on young women committed by a weird apparition known as Spring Heeled Jack, and to find out why werewolves are terrorizing London’s East End. Their investigations lead them to one of the defining events of the age, and the terrifying possibility that the world they inhabit shouldn’t exist at all!

We’re in total agreement David!

I felt just the same. The prose and character work was excellent. The larger story was unsatisfying, especially compared to…

Hmmm. I think I'll pass.

COMMENT Was I hinting that? I wasn't aware of it. But now that you mention it.... 🤔

So it sounds like you're hinting Fox may have had three or so different incomplete stories that he stitched together,…