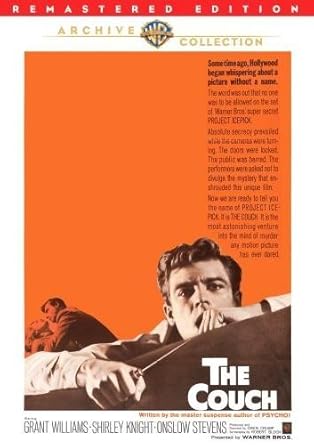

![]() The Couch directed by Owen Crump

The Couch directed by Owen Crump

In November 1960, filmgoers were presented with a very unique film, Girl of the Night. In it, we meet a call girl/prostitute named Bobbie Williams, played by the great Anne Francis in the screen role that she would go on to cite as her personal favorite of all her many performances. We learn about Bobbie via her visits to the psychiatrist (Lloyd Nolan) who is treating her, and these intimate encounters are alternated with glimpses of the young woman’s sordid daily life. Flash forward around 15 months, and another film would be released with very much the same modus operandi, but in this later film, the subject was male, and his life is shown to be more disturbing, as well as a lot more dangerous to the populace at large, than Bobbie’s ever was. That film was indeed The Couch, a little-discussed film today (not to be confused with the Andy Warhol film of 1964 that was simply entitled Couch) that yet proved very entertaining and rewarding for this viewer upon a first watch the other night. Released in February ’62, the film boasts some very impressive talents both in front of and behind the cameras, and is surely one ripe for discovery, now some six decades later.

In November 1960, filmgoers were presented with a very unique film, Girl of the Night. In it, we meet a call girl/prostitute named Bobbie Williams, played by the great Anne Francis in the screen role that she would go on to cite as her personal favorite of all her many performances. We learn about Bobbie via her visits to the psychiatrist (Lloyd Nolan) who is treating her, and these intimate encounters are alternated with glimpses of the young woman’s sordid daily life. Flash forward around 15 months, and another film would be released with very much the same modus operandi, but in this later film, the subject was male, and his life is shown to be more disturbing, as well as a lot more dangerous to the populace at large, than Bobbie’s ever was. That film was indeed The Couch, a little-discussed film today (not to be confused with the Andy Warhol film of 1964 that was simply entitled Couch) that yet proved very entertaining and rewarding for this viewer upon a first watch the other night. Released in February ’62, the film boasts some very impressive talents both in front of and behind the cameras, and is surely one ripe for discovery, now some six decades later.

The Couch opens with a man, who we viewers are only allowed to see from behind, phoning the LAPD and then speaking to one Lt. Kritzman (Simon Scott). The caller informs the cop that a murder will soon be taking place — at 7 p.m. that evening, to be precise — and that he himself will be the murderer. As good as his word, our unknown “gentleman caller” hangs up the phone, approaches a stranger on the crowded sidewalks of L.A., and sticks an ice pick into the man’s back, after which he calmly goes to his 7:00 appointment with his psychiatrist. As we soon learn, the killer is named Charles Campbell, played by none other than Grant Williams, who had previously appeared in three memorable sci-fi films over the course of the previous five years: The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Monolith Monsters and The Leech Woman. Campbell had just served two years in jail for beating and raping the daughter of his college professor, and is now being analyzed by one Dr. Janz (Onslow Stevens, whose film career stretched all the way back to 1931, and here appearing in his final picture), following his release. Campbell is also secretly dating Janz’ young niece and current receptionist, Terry Ames (gorgeous Shirley Knight, who this viewer knew primarily from her appearance in the superlative Outer Limits episode “The Man Who Was Never Born,” which was released the following year).

As in Girl of the Night, we learn about Campbell’s sorry past via his in-office discussions with the doctor; of the love he had for his sister, of his hatred for his widower father, of his current problems with young women, etc. We also see something of his “home life,” living in a boardinghouse where his landlady’s pretty daughter, Jean Quimby (Anne Helm, primarily known to this viewer via her three exceptionally fine appearances in TV’s Route 66), teases and banters with him relentlessly. And, finally, we see Campbell kill again, once more alerting Lt. Kritzman of his plans, and then prepare to kill yet one more time. And his third victim, it would appear, will be Dr. Janz himself…

The Couch boasts several extremely well-done sequences, including those first two murders, both on the crowded, nighttime streets of Los Angeles, and the third attempt, on Dr. Janz, in a packed football stadium. Other memorable sequences include Campbell’s two dates with Terry, one overlooking a crowded freeway and the other at the abandoned estate grounds of the lunatic’s grandfather. But best of all, perhaps, is the film’s culminating sequence, as Campbell dons a surgical mask and gown to finish off his botched slaying of Dr. Janz, as the shrink lies in a recovery room in hospital. Grant Williams, I should add here, is truly excellent as the homicidal wackadoodle, whose creepiness manages to come through the charm and the good-looking exterior; Lord only knows what Terry ever sees in him. Her judgment in men, it would seem, is truly suspect.

Director/producer Owen Crump manages to elicit not only a splendid performance from his leading man here but from all the others in the cast as well. He also brings a noirish feel to the proceedings, never more so than when Campbell walks the streets of L.A. at night, the camera showing us his handsome features in stark close-up. Crump is a director who was entirely new to me — his previous endeavors seem to consist mainly of documentaries and for TV, besides one or two minor films — but his work here indicates that he could have gone on to a fine career as a movie director, had he chosen to. He and one Blake Edwards (yes, that Blake Edwards, who, by the way, had been born William Blake Crump, although I can find nothing on the Interwebs to indicate that the two were related!) came up with the story idea for this film, and fortunately, allowed the great sci-fi and horror author Robert Bloch to come up with a screenplay. And this Bloch did in spades, in his very first bit of writing for the big screen; his 1959 novel Psycho had been adapted by Joseph Stefano for the classic Hitchcock film two years earlier, of course.

Bloch would go on to create screenplays during the 1960s depicting the shenanigans of several other twisted minds, in films such as The Cabinet of Caligari, Strait-Jacket and The Night Watcher — just as Blake Edwards would follow up this one with the terrific Experiment in Terror, another film about a West Coast serial killer, two months later — and Bloch’s screenplay here already evinces the sly wit and mastery of suspense for which the writer was already known on the printed page. I love when a cop tells Kritzman, regarding Campbell’s first victim, “He came out here to retire,” and Kritzman replies “That he did!” Add in some fine lensing by DOP Harold Stine and a moody and evocative score by Frank Perkins and you have a surprisingly fine entertainment, both moving and nerve racking.

And yet, there are some minor problems to be encountered here. For one thing, this viewer found the psychological explanation for Campbell’s homicidal mania to be a bit forced and unconvincing; either that, or the young man was already seriously disturbed, mentally, even as a youth. Throughout the film, the LAPD wonders why the killer insists on killing only at 7 p.m., and why he only uses an ice pick to commit his homicides, and the viewer cannot help wondering the same thing. Unfortunately, we never do learn the answers to those riddles to our satisfaction … unless it is that 7 p.m. is the time for his nightly psychiatric appointments, providing him with a convenient alibi? But these are minor matters.

The film, as a whole, must be deemed some kind of success, in no small part due to Williams’ fine performance. Viewers who have only seen the actor perform as the ever-dwindling yet heroic Scott Carey in the wonderful film The Incredible Shrinking Man — truly, one of the sci-fi champs of the 1950s — might be a tad surprised at how vastly different a character he essays here. Campbell is never what you would call a likeable person, handsome and at times charming as he might be, but Williams does make us feel for him, at least. As was the case with another moodily shot, B&W film that I recently experienced, 1964’s The Strangler, in which Victor Buono portrayed a serial killer who also had his problems with the ladies (to put it mildly), here, our lead actor makes us sympathize for the demented killer, without necessarily liking him. The two films would make for one perfectly paired double feature, come to think of it, both being very finely acted and directed exercises in suspense and mental aberration; no wonder the great cable station TCM showed these two films back to back recently. The films have numerous similarities as well as differences. Buono’s maniac character, Leo Kroll, is shown to have mother issues, whereas Campbell most assuredly has had a problem with his father. Kroll, as hinted at by his film’s title, prefers to throttle his victims, whereas Campbell goes for the more phallic ice pick. Kroll, being decidedly obese, finds it impossible to pull in the ladies, whereas Campbell is a handsome charmer and seems to attract them wherever he goes.

But as is shown in both films, both characters are very seriously unhinged, and completely remorseless after their cold-blooded killings. I do recommend them both to your attention, and preferably watched in the order in which they first appeared. By the end of The Couch, the viewer will surely come to the conclusion that one couch is not enough for a character such as Charles Campbell; this dude requires an entire psychiatric ward all to himself!

You’re the only person I know who could make the phrase, “homicidal wackadoodle” work!

Thanks, Marion! 😁 So much better than “murderous nutburger,” right?