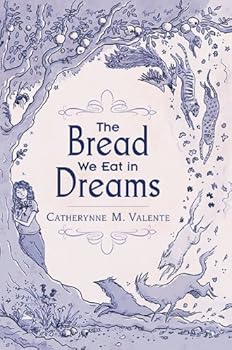

![]() The Bread We Eat in Dreams by Catherynne Valente

The Bread We Eat in Dreams by Catherynne Valente

The Bread We Eat in Dreams contains thirty-five of Catherynne Valente’s short stories and novellas, caught out in the wild and arranged neatly for the paying public. Ranging from delicate, herbivorous poems to novella-sized megafauna, these creatures display the ecological diversity of the Phylum of the Fantastic and the continued resonance of the Kingdom of Myth. For gentlemen-scientists and enthusiastic students of all things speculative, Valente’s story-menagerie is worth the visit.

Thirty-five stories cannot be summarized in any meaningful sense, particularly when they are such willful, strange, and wild stories. There are warped retellings of fairytales — at least one witch plucks an apple from a tree, and little red riding hood has grown awfully postmodern and bitter over the years (“The Red Girl”). There are dystopian future-worlds ruled by women with a hundred hands, where the word for sin is also the word for tiger (“Aeromaus”). There are stories which are more like humorous, bulleted essays (“Twenty-Five Facts about Santa Claus”). There are even a couple of teenage-ish urban fantasies with honest-to-god vampires and fairy worlds (“In the Future When All’s Well,” and “A Voice like a Hole”). There are poems, too, but I wouldn’t be able to review a poem if it came with a labeled diagram and an instruction manual, so we won’t mention them again.

The two best stories are crammed next to each other at the very front. The Locus Award-winning “White Lines on a Green Field” had me from the very first line: “Let me tell you about the year Coyote took the Devils to the State Championship.” Now, I’ve never met a Coyote story I didn’t like — I suspect that trickster gods and fantasy readers are natural allies, because we so love to be tricked — but this one is my new favorite. Coyote lends his godly charm to an American high school and everything amplifies. All the cheerleaders are pregnant, there are ecstasy tabs in everyone’s lockers, and the football team is unbeatable. It’s heady and sharp-toothed and surprisingly dark at its heart.

“The Bread We Eat in Dreams” is the other story that has set up permanent camp in my brain. It’s about a demon cast out of hell who takes up residence in colonial Maine, and is eventually and ineffectually burned at the stake. This is a preference based only partially on the random roulette of my own experiences (I raked blueberries for two seasons in the wild north of Maine), but mostly on the powerful combination of humor, history, and a character who was formerly the baker of hell.

Above all, these stories are portraits of the writer at play. Or, if she’s not playing — if Catherynne Valente has to sweat and snatch at the words like everybody else, and drag them screaming over the coals simply to get them to stand in a neat sentence — then it’s exceptionally well-hidden. Valente dances and toys with her words, and leads her readers on merry jigs through unfamiliar places. While her tone might slip and shift between stories (and not always successfully; Valente as Valley Girl Vampire was just a hair shy of mocking), there is always the same element of lyrical, playful abandon.

But a clever author at play is, of course, a very serious matter indeed, because they’re rarely satisfied with words alone. Soon they’re toying with narratives and structures, and then they’re poking fun at our dearest cultural narratives. Even Santa is not sacred; he and the elves are involved in a “mythologically lucrative profession and a logical labor-sharing commune.” Also, his list “isn’t about naughty and nice,” because coal is really a very useful gift when you think about it. It’s really about “whether or not you need to figure out the lesson of the coal.”

Valente is at her most wonderfully vicious when she deals with gender narratives. “A witch is just a girl who knows her mind,” she tells us. “Girls will be girls,” she adds comfortingly, referring to a minotaur girl who is possibly-literally consuming the football quarterback. Valente’s women are monstrous, deified, clever, athletic, evil, and honorable, and so much more than “strong.” We need more of them.

For flexible readers who are not put off by knee-deep mythological references, and who are familiar with a few of the genera of fantasy, and who don’t mind an author gleefully overturning their expectations, The Bread We Eat in Dreams is a pure pleasure.

“There are poems, too, but I wouldn’t be able to review a poem if it came with a labeled diagram and an instruction manual, so we won’t mention them again.”

Alix, no one knows how to review a poem, that’s the secret.

I mean, I seriously have a pass-fail process for poetry: I like it. Or, I don’t like it. Meaty literary criticism, sure to delight the masses.