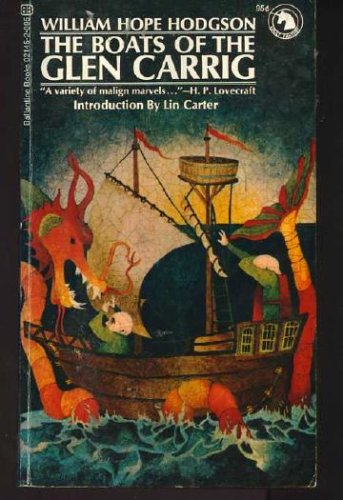

![]() The Boats of the Glen Carrig by William Hope Hodgson

The Boats of the Glen Carrig by William Hope Hodgson

The conventional words of wisdom for any aspiring new author have long been “write what you know,” a bit of advice that English author William Hope Hodgson seemingly took to heart with his first published novel, The Boats of the Glen Carrig. Before embarking on his writing career, Hodgson had spent eight years at sea, first as an apprentice for four years and then, after a two-year break, as a third mate for another long stretch. And those hard years spent at sea were put to good use not only in The Boats of the Glen Carrig, but in his third novel, The Ghost Pirates, and in many of his short stories and poems as well. According to August Derleth, “No other writer — not Conrad nor Melville nor any other — has so consistently dealt with the eternal mystery of the sea,” a sentiment very closely echoed by Lin Carter in his excellent introduction to The Boats of the Glen Carrig in the Ballantine Adult Fantasy edition.

The Boats of the Glen Carrig is in many ways a remarkable book. It takes the form of a saga of survival narrated by John Winterstraw to his son in the year 1757, and tells of what happened to the two remaining lifeboats after the sudden sinking of the Glen Carrig. The survivors had drifted for many days before coming upon a desolate swampland (referred to by Winterstraw as the Land of Lonesomeness), replete with strange wailing noises and some decidedly nasty arboreal life. After fleeing this inhospitable land and surviving a horrible storm, one of the boats had fetched upon a small island in the middle of a gigantic area of entangling seaweed.

Their adventures on this unusual island make up the bulk of Winterstraw’s narration, and what a strange tale it is! Indeed, this island almost makes the one featured on the hit TV series Lost seem normal, surrounded and infested as it is with giant crab monsters (could Roger Corman be a fan of this book?), humongous octopi (think 1955’s It Came From Beneath the Sea) and, most memorably [Possible spoiler, highlight if you want to read it:], the weed men: pale, slimy, vampiric, bipedal slug creatures that swarm in the hundreds and attack both on land and at sea. [end possible spoiler]. Between fending off attacks from the nasty animal life on the island, seeking food and water, and attempting the rescue of an old, manned sailing vessel that had been trapped for years in the seaweed morass, the Glen Carrig survivors surely do have their hands full.

But a capsule description of this novel cannot possibly succeed in conveying the eeriness of the book, or its outré sense of mood and otherworldliness. Hodgson has his Winterstraw narrator speak in a seemingly pseudo-archaic language that may initially put some readers off, but that (for me, anyhow) lends to an unusual veracity nevertheless, as well as strangeness. A single sentence can easily run on for 2/3 of a page in this novel, with six or seven semicoloned sections. The grammar and syntax used are quite bizarro, an expedient that Hodgson also used in his 1912 epic novel The Night Land. In that later novel, this invented form of English was meant to convey the language of some billions of years hence; here, it stands in for an 18th century English that probably never was. Hodgson also uses many nautical terms that may send modern-day readers scurrying for their dictionaries, but most of those readers will not mind, being more than content with this short novel’s rapid pacing, creepy atmosphere and, above all, truly frightening monsters. Not for nothing was this book chosen for inclusion in Jones’ & Newman’s excellent overview volume Horror: Another 100 Best Books. Though the only characters we really get to know with any degree of depth are our narrator and the remarkably intrepid bo’sun leader of the men, the book is as memorable as can be, and concludes most satisfactorily.

(On a side note, sharp-eyed readers may have noticed that in my first sentence above, I refer to The Boats of the Glen Carrig as Hodgson’s “first published novel” rather than his “first novel,” and that is because there seems to be some confusion on this point. In his scholarly Internet essay Writing Backwards: The Novels of William Hope Hodgson, Sam Gafford makes a convincing case for The Boats of the Glen Carrig being Hodgson’s last novel, and The Night Land his first… in direct opposition to the order long believed to have been the case! Using internal evidence from a batch of recently unearthed Hodgson letters, Gafford really does press his point home….)

Do it! One of the best things I've read in recent years.

This reminds me. I want to read Addie LaRue.

We’re in total agreement David!

I felt just the same. The prose and character work was excellent. The larger story was unsatisfying, especially compared to…

Hmmm. I think I'll pass.