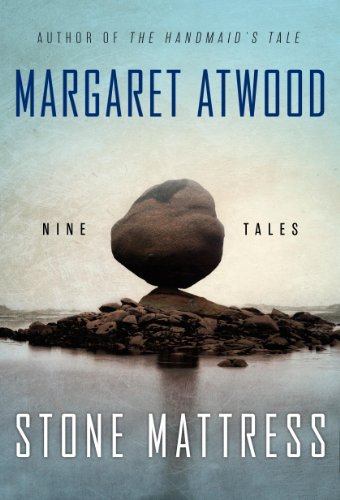

![]() Stone Mattress: Nine Tales by Margaret Atwood

Stone Mattress: Nine Tales by Margaret Atwood

Margaret Atwood is hardly an unappreciated author. Booker winner, seemingly constant nominee for the Orange and Booker prizes, Harvard Arts Medal, Orion Book Award, and the list goes on. But one thing I’d say she doesn’t get enough credit for is her humorous touch, which can be scathingly, bitingly funny, and which is on frequent display in her newest collection of short stories, Stone Mattress: Nine Tales.

The anthology is comprised of nine “tales” (in the afterword, Atwood explains why she prefers that descriptor), the first three of which — “Alphinland”, “Revenant”, and “Dark Lady” are tightly linked by character and events. The others are independent, though they do share some similar themes and characters — vengeance, the travails (and pleasures) of aging, a deliciously macabre tone. Like nearly all such collections, some stories are more successful than others, but, and this is rare for me with regard to story collections, I enjoyed every one. And of course, this being Atwood, even the “lesser” stories are stylistically and technically well-written.

The linked stories center on a trio of aged characters who knew each other in their younger, more bohemian days: Gavin, a somewhat pretentious and wholly unlikable poet; Constance, his girlfriend whose fame and income outstrips Gavin’s after she creates a fantasy land called Alphinland; and Marjorie, with whom Gavin cheated on Constance. “Alphinland” introduces Constance not long after she’s lost her long-time husband, whose voice she still hears advising her, in this particular instance about how to survive the terrible winter storm shutting down Toronto for a few days. “Revenant” shifts us to Florida, where the irascible Gavin is being hectored by his most recent wife into an interview with a student interested in his work. Finally, in “Dark Lady,” we’re in Marjorie’s brother’s POV as he witnesses the three old acquaintances brought together one last time.

The changing points-of-view allow us to see events from three different perspectives and like the characters themselves, sometimes we are surprised to learn we were laboring under a misconception or two. All three are richly, distinctively drawn. It’s hard as well not to think Atwood is having some fun here with the idea of genre vs. literary fiction and her own experiences in both worlds and in that debate. Here, for instance, is Constance thinking about her fans:

She also declines to engage in social media, despite her publisher’s constant urging… she has no wish to interact with her devoted readers; she knows too much about them already, them and their body piercings and tattoos and dragon fetishes. Above all, she doesn’t want to disappoint them. They’d be expecting a raven-haired sorceress with a snake bracelet on her upper arm… instead of a wispy, soft-spoken paperthin exblonde.

Gavin, meanwhile, is hysterically acerbic, as when he thinks of his wife and children after his eventual death:

Reynolds won’t leave him… She’s polishing up her widow act… She’s so competitive that she’ll hang in there to make sure neither of the two previous wives lay claim to any part of him… She’ll also want to cut out his two children… He hadn’t paid much attention to them when they were babies — they and their pastel urine-soaked paraphernalia… and he’d decamped in each case before they were three — so they don’t like him very much, nor does he blame them, having hated his own father… there’ sure to be some squabbling after the funeral; he’s making sure of that by not finalizing his will. If only he could hover around in mid-air to watch.

After seeing Ewan, Constance’s husband, apparently do just that in the first story, one wonders if Gavin will get his wish. In the last story, “Dark Lady,” Marjorie’s brother Tin is the grudging witness to “Jorie’s” attempt to settle old scores, though things don’t go as expected of course.

Vengeance, writers, and genre play major roles in “The Dead Hand Loves You,” about an older writer tired of being bound by the contract he signed decades earlier in his callow youth agreeing to share the profits from his as yet unwritten novel. An aged character seeking revenge for being wronged in her youth is also at the core of the title story, which is set on an Antarctic tour cruise (Atwood explains she and her husband actually came up with this story on a cruise of their own so as to entertain fellow travelers). Both stories were solid, but neither stood out much for me, though Verna, the protagonist in “Stone Mattress” is a great character.

“Lusus Naturae,” about a young girl/vampire, was more successful, conveying a wonderfully poignant sense of the girl’s coming of age, which involves understanding what she is and what that means for her family and her future. It’s a lovely story and I actually wished Atwood had given us more pages of it.

“Zenia with the Bright Red Teeth” was another lesser story in my mind, but as it returned us to the familiar characters of The Robber Bride, I enjoyed it anyway.

Along with the first three, one of my favorites was “Torch the Dusties,” “dusties” being the slang term hurled at the elderly by a terrorist group that calls itself “Our Turn,” whose premise is that the old people have left the young a mess of a world and so need to make room and stop taking up valuable resources. The two main characters, residents of the Ambrosia Manor, an assisted living and full-time care center, are Wilma and Tobias. Wilma is suffering from macular degeneration (“Macular sounds so immoral, the opposite of immaculate”) and Charles Bonnet’s Syndrome (she sees hallucinations of tiny little people). Tobias, meanwhile, is an ultra urbane ladies man whose tales Wilma is never quite trusting of.

It is in this story that we’re presented with one of the constant themes of the collection as a whole:

You believed you could transcend the body as you aged, she tells herself. You believed you could rise above it, to a serene, non-physical realm. But it’s only through ecstasy you can do that, and ecstasy is achieved through the body itself. Without the bone and sinew of wings, no flight. Without that ecstasy you can only be dragged further down the body, into its machinery. Its rusting, creaking, vengeful, brute machinery.

For all the scathing satire, the sharply funny bits of dialogue and interior monologue, the fun with genre and literary criticism, the fantasy elements, what I responded most to was generally Atwood’s top-of-her-game facility in creating real, wholly alive characters and specifically, the rich detail with which we entered into the lives of such older characters. The taut suspense of Constance navigating the icy streets of Toronto on a quest for salt, the evocation of moving through a barely seen world as seen through Wilma, Gavin’s acknowledgement that “his regret is that he isn’t a lecherous old man, but he wishes he were. He wishes he still could be,” and the way these characters take action — Constance going on her quest for salt, Verna seeking her vengeance, Tobias and Wilma refusing to just knuckle under to the fear and terror.

At this point in Atwood’s well-known career, there’s little to say about her style or prose beyond that it is exactly at the high level one has grown to expect from her by now. A new work by Atwood is always a treat, and Stone Mattress is no exception. Recommended.

Excellent review, Bill, and I’m glad we won’t have to wait 100 years to read this one.