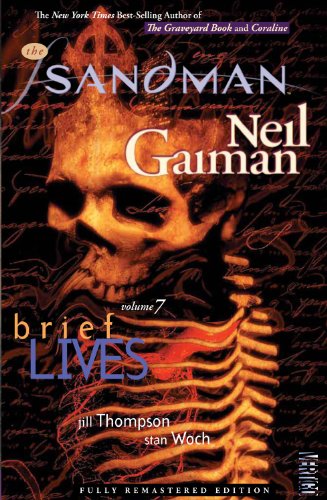

![]() The Sandman (Vol. 7): Brief Lives by Neil Gaiman

The Sandman (Vol. 7): Brief Lives by Neil Gaiman

The Sandman Volume 7, Brief Lives, offers a nice contrast to Volume 6, Fables and Reflections. Whereas Fables and Reflections offered nine unrelated tales in terms of plot and characters (there are thematic connections, of course), Brief Lives is a single story, an adventure tale, a road trip. Dream goes on a journey with his youngest sister, Delirium.

The Sandman Volume 7, Brief Lives, offers a nice contrast to Volume 6, Fables and Reflections. Whereas Fables and Reflections offered nine unrelated tales in terms of plot and characters (there are thematic connections, of course), Brief Lives is a single story, an adventure tale, a road trip. Dream goes on a journey with his youngest sister, Delirium.

Their need to go on this journey is set up in previous books. Repeatedly, the family of the Endless mention their elder missing brother, and they do so rarely by name; however, in Fables and Reflections we finally learn a little bit about him — Destruction. We even get a story that takes place in the past, a story about the Sandman’s son Orpheus, in which Destruction is featured. Surprisingly, Destruction is full of laughter and a love of life. We get to see him offer advice to Orpheus, who perhaps should be a little bit more wary of accepting advice from the personification of Destruction, even if he is his uncle. Family isn’t always trustworthy. Please read Fables and Reflections to see how following Destruction’s advice turns out.

Whereas Dream was not always the main focus of the nine stories in Fables and Reflections, he stays on the main stage for most of the action of Brief Lives; however, we do take breaks from Sandman, finding out what is going on with Delirium and periodically checking in with Destruction, who is hiding out, and we also meet up with various characters Delirium and Sandman are seeking out.

The story starts out with a brief visit with Orpheus in the present day, to see how he spends his time, but quickly we are whisked away to Delirium’s adventures. Apparently, Delirium, who once was Delight, has trouble staying focused, even for one or two sentences, but, we find out, when she gets obsessed with an idea, she does not forget about it and will go to any lengths to accomplish her goals. Her latest obsession is this desire to seek out and find her long-lost missing brother, Destruction, whom she loves dearly. Delirium first goes to Desire, who ironically tries to squash Delirium’s own desire to find her brother (the Sandman will eventually accuse Desire of creating Delirium’s obsessive desire in the first place); after Desire refuses to help her, Delirium seeks out Despair’s help. The scene in which Delirium enters the realm of Despair is a moving one. However, again Delirium finds no offer of help. Finally, she goes to Dream who agrees to go with her on her journey, though he is less than forthcoming about his own reasons for going with her.

There is much humor in Brief Lives. First, of course, is the humor in the premise. To merely summarize the plot is to invite humor: Dream and Delirium go on a road trip in search of Destruction. That can’t be good, we must say to ourselves, when Delirium seeks Destruction. What good can come from such a pursuit? And to be aided by Dream? What exactly is Gaiman implying here? What can be the good of anyone seeking Destruction? There is further humor in many of the scenes. Delirium is almost always amusing because of her bewildering observations about what is going on around her, as well as her childlike fascination with all she sees. When Dream announces that they must travel through the physical realm, we get to see Delirium’s excitement on a plane, we get her commentary on the idea of being in the clouds and the reality of actually stepping into them, and we watch her disappointment at being told by Dream that she cannot drive the car, that instead the chauffer will be driving (however, after the chauffer leaves, under dark circumstances, we do get even more humor at watching Delirium get a chance at the wheel. How do you think she’d react if, say, she got pulled over by a cop for driving like the little girl she appears to be?)

There is much humor in Brief Lives. First, of course, is the humor in the premise. To merely summarize the plot is to invite humor: Dream and Delirium go on a road trip in search of Destruction. That can’t be good, we must say to ourselves, when Delirium seeks Destruction. What good can come from such a pursuit? And to be aided by Dream? What exactly is Gaiman implying here? What can be the good of anyone seeking Destruction? There is further humor in many of the scenes. Delirium is almost always amusing because of her bewildering observations about what is going on around her, as well as her childlike fascination with all she sees. When Dream announces that they must travel through the physical realm, we get to see Delirium’s excitement on a plane, we get her commentary on the idea of being in the clouds and the reality of actually stepping into them, and we watch her disappointment at being told by Dream that she cannot drive the car, that instead the chauffer will be driving (however, after the chauffer leaves, under dark circumstances, we do get even more humor at watching Delirium get a chance at the wheel. How do you think she’d react if, say, she got pulled over by a cop for driving like the little girl she appears to be?)

Underneath this humor is a darkness that is summed up by this volume’s title — Brief Lives. We spend most of our time in this storyline with immortal beings, even a few beings who are not of the Endless, and we find out a few of them, even though they may be gods, are not quite as immortal as they, or we, thought. But the lives of the humans they encounter are like the blink of an eye to the Endless and other long-lived beings — as a result, they are wary of getting too attached to these human creatures. It’s an odd perspective for us as readers, being the humans that we are.

Destruction gives some of the best commentary on the topic of our Brief Lives, because, as Gaiman suggests, no matter how long we live, to a certain extent all our lives are brief in that they are all transitory in the grand scheme that is Time Eternal. Destruction’s philosophizing emerges out of his mentioning his love of looking at the stars because they give the “illusion of permanence”: “I like the stars. It’s the illusion of permanence, I think. I mean, they’re always flaring up and caving in and going out. But from here, I can pretend . . . I can pretend that things last. I can pretend that lives last longer than moments. Gods come, and Gods go. Mortals flicker and flash and fade. World’s don’t last; and stars and galaxies are transient, fleeting things that twinkle like fireflies and vanish into cold and dust. But I can pretend.” And while we all seem to get different allotments of time, as Death says to one of the recently deceased, “You lived what anybody gets . . . You got a lifetime. No more. No less. You got a lifetime.” No matter how long or how brief, we all get no more and no less than exactly one lifetime, or at least that’s the perspective offered to us by Gaiman via the personification of Death who watches over the passing of all things.

Destruction gives some of the best commentary on the topic of our Brief Lives, because, as Gaiman suggests, no matter how long we live, to a certain extent all our lives are brief in that they are all transitory in the grand scheme that is Time Eternal. Destruction’s philosophizing emerges out of his mentioning his love of looking at the stars because they give the “illusion of permanence”: “I like the stars. It’s the illusion of permanence, I think. I mean, they’re always flaring up and caving in and going out. But from here, I can pretend . . . I can pretend that things last. I can pretend that lives last longer than moments. Gods come, and Gods go. Mortals flicker and flash and fade. World’s don’t last; and stars and galaxies are transient, fleeting things that twinkle like fireflies and vanish into cold and dust. But I can pretend.” And while we all seem to get different allotments of time, as Death says to one of the recently deceased, “You lived what anybody gets . . . You got a lifetime. No more. No less. You got a lifetime.” No matter how long or how brief, we all get no more and no less than exactly one lifetime, or at least that’s the perspective offered to us by Gaiman via the personification of Death who watches over the passing of all things.

Brief Lives also offers commentary on the nature of epistemology, or the realm of knowledge. What can we know in life and how can we know it? What are the limits, what is the scope, of knowledge? First, Gaiman suggests how grand “knowledge” is since even Dream and Delirium are limited in their knowledge. Unlike Destiny, they do not know all of the future, but there’s a suggestion in the book that even Destiny may not know everything, as Delirium lectures a somewhat smug Destiny: “There are things not in your book [of destiny]. There are paths outside this garden [in the realm of Destiny]. You would do well to remember that.” And yet Destruction remembers Death suggesting that we know more than we allow ourselves the awareness of knowing: “[Death] said everyone knows everything. We just pretend to ourselves we don’t.” Of course, such a claim is difficult to comprehend. What does it mean to say we all already know everything and just pretend that we don’t know it? Even Destruction finds such a statement confounding: “I never knew what to make of that,” he admits.

Brief Lives also offers commentary on the nature of epistemology, or the realm of knowledge. What can we know in life and how can we know it? What are the limits, what is the scope, of knowledge? First, Gaiman suggests how grand “knowledge” is since even Dream and Delirium are limited in their knowledge. Unlike Destiny, they do not know all of the future, but there’s a suggestion in the book that even Destiny may not know everything, as Delirium lectures a somewhat smug Destiny: “There are things not in your book [of destiny]. There are paths outside this garden [in the realm of Destiny]. You would do well to remember that.” And yet Destruction remembers Death suggesting that we know more than we allow ourselves the awareness of knowing: “[Death] said everyone knows everything. We just pretend to ourselves we don’t.” Of course, such a claim is difficult to comprehend. What does it mean to say we all already know everything and just pretend that we don’t know it? Even Destruction finds such a statement confounding: “I never knew what to make of that,” he admits.

But Delirium agrees that Death is partly right: “She is. Um. Right. Kind of.” At the same time, however, Delirium warns us of the danger of knowing too much: “Not knowing everything is all that makes it okay, sometimes.” This necessity we all have of not having too much knowledge reminds me of one of my favorite passages from Lovecraft, who, in “The Call of Cthulu” (1926) writes, “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

But Delirium agrees that Death is partly right: “She is. Um. Right. Kind of.” At the same time, however, Delirium warns us of the danger of knowing too much: “Not knowing everything is all that makes it okay, sometimes.” This necessity we all have of not having too much knowledge reminds me of one of my favorite passages from Lovecraft, who, in “The Call of Cthulu” (1926) writes, “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

Gaiman seems to imply a similar sentiment through Delirium’s commentary on Death’s claim about our access to more knowledge than we realize. Gaiman, through Delirium, suggests that the limits to our knowledge, in some areas at least, are for our own good. This limitation of knowledge is in many ways the basis of the plot of Brief Lives: Destruction has left his post and hidden himself away and nobody knows where he is. This knowledge is hidden even from such powerful beings as the Endless. In seeking out this knowledge, Dream and Delirium trigger a series of deadly events. There is a cost to seeking knowledge, Gaiman tells us. Sometimes the cost is to those around us as we blindly seek for answers. Sometimes, however, we pay the price personally, as Dream is forced to do when he must seek out an oracle, the only oracle with the knowledge of Destruction’s location, and it costs him much personally: He must face his past, literally, and deal with his own personal failures, which is exactly the type of acknowledgment that Dream, always full of pride, is hesitant to do. But, Gamain also implies that acknowledging personal failures is a kind of necessary personal knowledge if we are to change and grow over time, and the series of THE SANDMAN can be seen as the long maturation process of the main character, Dream.

Gaiman seems to imply a similar sentiment through Delirium’s commentary on Death’s claim about our access to more knowledge than we realize. Gaiman, through Delirium, suggests that the limits to our knowledge, in some areas at least, are for our own good. This limitation of knowledge is in many ways the basis of the plot of Brief Lives: Destruction has left his post and hidden himself away and nobody knows where he is. This knowledge is hidden even from such powerful beings as the Endless. In seeking out this knowledge, Dream and Delirium trigger a series of deadly events. There is a cost to seeking knowledge, Gaiman tells us. Sometimes the cost is to those around us as we blindly seek for answers. Sometimes, however, we pay the price personally, as Dream is forced to do when he must seek out an oracle, the only oracle with the knowledge of Destruction’s location, and it costs him much personally: He must face his past, literally, and deal with his own personal failures, which is exactly the type of acknowledgment that Dream, always full of pride, is hesitant to do. But, Gamain also implies that acknowledging personal failures is a kind of necessary personal knowledge if we are to change and grow over time, and the series of THE SANDMAN can be seen as the long maturation process of the main character, Dream.

The final issue ties everything together, offering us more insight into Dream and the changes he has gone through. All throughout this journey, he has been confronted by others’ commenting on how much he has changed, and he has resisted acknowledging the truth of these observations, but in the end, when he returns to the Dream realm, we watch him come to some sense of realization. We also see him act in certain ways that would not have been possible for the  being he was years before. Dream, Gaiman shows us, has indeed evolved in the course of the longest coming-of-age story ever written — thousands of years have passed before this angst-ridden, proud, teen-like being comes into his maturity, a maturity, according to Gaiman, that includes the ability to put others before one’s self, as well as the ability to let one’s pride diminish in acknowledging personal failures and flaws.

being he was years before. Dream, Gaiman shows us, has indeed evolved in the course of the longest coming-of-age story ever written — thousands of years have passed before this angst-ridden, proud, teen-like being comes into his maturity, a maturity, according to Gaiman, that includes the ability to put others before one’s self, as well as the ability to let one’s pride diminish in acknowledging personal failures and flaws.

Brief Lives is a near-perfect nine-part story with absolutely beautiful art by Jill Thompson. I cannot give this volume less than five stars. It’s worth reading through the less perfect moments of the series to get to this one volume, a culmination of much that has come before in terms of plot and theme.

~Brad Hawley

![]() After the stand-alone story collection Vol 6: Fables and Reflections, Vol 7: Brief Lives brings the focus back on Morpheus’ dysfunctional family, the Endless. For a group of avatars representing some fundamental concepts that underpin human existence (but only those that start with ‘D’), they can’t seem to get along or understand each other much of the time. So it’s no surprise they also have trouble empathizing with mere mortals and their brief lives. In fact, as we learn from Death in this volume, each of us is only allotted a single lifetime, and whether we consider it brief or long in human terms, it is less than the blink of an eye for the Endless, who fulfill their duties according to higher rules than we can fathom, in a strange relationship with humans in which neither is ruled or ruler, master or slave, and yet they are inextricably linked.

After the stand-alone story collection Vol 6: Fables and Reflections, Vol 7: Brief Lives brings the focus back on Morpheus’ dysfunctional family, the Endless. For a group of avatars representing some fundamental concepts that underpin human existence (but only those that start with ‘D’), they can’t seem to get along or understand each other much of the time. So it’s no surprise they also have trouble empathizing with mere mortals and their brief lives. In fact, as we learn from Death in this volume, each of us is only allotted a single lifetime, and whether we consider it brief or long in human terms, it is less than the blink of an eye for the Endless, who fulfill their duties according to higher rules than we can fathom, in a strange relationship with humans in which neither is ruled or ruler, master or slave, and yet they are inextricably linked.

In Brief Lives, the youngest and most unstable of the Endless, Delirium (who was once Delight) decides that she must seek after her long-lost brother Destruction, who left his duties for whereabouts unknown 300 years ago. She tries to enlist the aid of Desire and Despair with no success, and finally approaches her elder brother Dream, who is very much the opposite of her scattered madness, a cool, aloof, and overly-proud individual who takes his duties very seriously (unless he is entangled in another troubled romantic relationship). Dream agrees to help her out, but his reasons are not made clear.

What ensures is a very strange road-trip indeed, in which Delirium and Dream track down a strange list of long-lived beings, some previously divinities of note now facing hard times, who might know the whereabouts of Destruction. However, not only do they discover no viable leads, but bad things seem to happen to those around them. Eventually Death abruptly decides to end the quest, putting Delirium in a sulk, and it falls to Death to set Morpheus straight and on the path to reconciliation with his emotionally fragile younger sister.

They resume their quest, but the only viable source of information is one that Morpheus is loathe to pursue, since it will require that he face up to some harsh decisions he made in the past (see “The Song of Orpheus” in Vol 6). Nonetheless, Morpheus does soldier on, and in the process we see that even the Endless can change, for “Endless” is not the same as “Unchanging.” Throughout the series we have seen Dream being forced by various circumstances and people to face up to his rigid and inflexible attitudes and brittle pride, and admit fault.

This idea that even the Endless can change is perfectly illustrated by Destruction, who abandoned his duties three centuries previous, and now leads a quite and secluded existence painting, cooking, sculpting, and various other forms of creation. Is it a surprise that the Lord of Destruction also takes such a keen interest in creation? It’s a nice literal reminder of the dual nature of creation and destruction. Who would have though he was such an agreeable character. It’s interesting that we never really see him ‘on the job’ on the battlefield, triggering natural disasters, etc. Even when he is briefly seen on the Earth during the Black Plague, his feelings seem subdued. Is he a classic case of burnout, perhaps?

In any case, the volume ends with the fateful meeting of Dream, Delirium, and prodigal brother Destruction. His reasons for abandoning his duties are quite compelling, and her reveals a number of insights on what the Endless themselves are, though he again dances around the topic of why they exist and who created them. This is true throughout the series — it plays fairly coy when it comes to mentioning the Creator of the Universe, though his presence is indirectly felt. And the climactic decision of Destruction leaves plenty of room for further reflection, if not directly answering those questions. However, there is a sense that we are approaching the resolution of some major plot elements in the coming three volumes.

~Stuart Starosta

I always liked Delirium’s relationship with Dream. She was the only one besides Death who could call him to account, it seemed, and have him listen. He was always polite to Destiny but there was never a sense that he was taking things to heart. When his two sisters, it seemed that he did.

Brad, a pleasure to read your review of Brief Lives – you’ve captured all the key themes and quotes that I thought were worthy of note, and have explained them far better than I ever could. In particular, I was very impressed by the Lovecraft “Call of Chthulu” quote, which is the most perfect articulation of the limitations of science and dangers of total understanding. Makes we want to read some Lovecraft as he seems to have understood things back in 1926 as well as anyone today.