I’ve always thought that the novella was a perfect length for short science fiction or fantasy, because it gives an author space enough to build a complete world and form characters who live and breathe in the reader’s imagination. You need more room to do this in these genres than in mainstream literature, where an author can assume that the reader is at home in the world of his characters. Yet a novella is also short enough to be read in a single sitting – a perfect lunchtime read, for instance – and a reader can take in an author’s entire milieu and ideas in one gulp. Where copies of the novellas are available online for those who wish to read them, I have linked them so that you can have as good a week of lunches this week as I had last.

There are six novellas nominated for the Nebula this year. They are all of exceptionally high quality, and the variety is enormous, so much so that comparison of one to another seems almost silly. The jury is going to have a heck of a time choosing a winner.

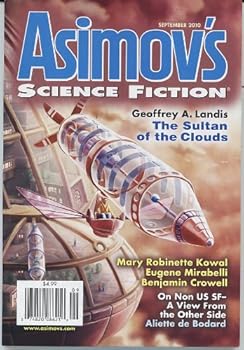

My personal favorite for the win is one of the two hard science fiction stories, “The Sultan of the Clouds” by Geoffrey A. Landis, originally published in the September 2010 issue of Asimov’s. This story is bursting with traditional sensawunda (that’s “sense of wonder” for the uninitiated); the ideas and innovations burst from every page. Want to live on Venus? Here’s how. Actually, you can’t live on the planet; the acidic atmosphere would strip the flesh from your dead bones after you were crushed by the atmospheric pressure. But you could live in a cloud city above the atmosphere, in a closed environment. What kind of society would develop in such cities? Landis posits a society built even more on money than we have going right now, with great wealth buying enormous privilege by a few families who come to rule the planet. Of course, there’s always an underground in such societies, isn’t there?

My personal favorite for the win is one of the two hard science fiction stories, “The Sultan of the Clouds” by Geoffrey A. Landis, originally published in the September 2010 issue of Asimov’s. This story is bursting with traditional sensawunda (that’s “sense of wonder” for the uninitiated); the ideas and innovations burst from every page. Want to live on Venus? Here’s how. Actually, you can’t live on the planet; the acidic atmosphere would strip the flesh from your dead bones after you were crushed by the atmospheric pressure. But you could live in a cloud city above the atmosphere, in a closed environment. What kind of society would develop in such cities? Landis posits a society built even more on money than we have going right now, with great wealth buying enormous privilege by a few families who come to rule the planet. Of course, there’s always an underground in such societies, isn’t there?

More directly, Landis’s story concerns Leah Hamakawa, an accomplished ecologist, and the man who loves her but is afraid to tell her so, her assistant, David Tinkerman. Hamakawa is invited to Venus by Carlos Fernando Delacroix Ortega de la Jolla y Nordwald-Gruenbaum, one of the satraps of Venus who is, it turns out, only 12 Earth years old. On Venus, that is not too young to be considering marriage, and it quickly becomes apparent that Carlos has his eye on Hamakawa. But that isn’t the only reason he has invited her to Venus; he wants to talk to her about terraforming the planet. That seems scientifically impossible, but Carlos is more devious than you would expect of a 12-year-old. Sociology and physics blend beautifully here. Science never overwhelms the story, and the infodumps needed to place the reader fully into the context are painless and well-written. It’s a wonderful blend of erudition and entertainment. I’d be delighted to see this story take the prize.

The other hard science fiction story nominated is Ted Chiang’s “The Lifecycle of Software Objects.” Usually if Chiang’s name is on a prize ballot, you can predict with confidence that he will be the winner, but I thought Chiang had a rare miss with this story of software pets, called digients, that develop personalities through interaction with their owners. Chiang poses a number of interesting ethical questions regarding what obligations, if any, humans might own to such creations; can you simply choose never again to boot up an artificial intelligence if you get tired of it? This is one case in which the novella length failed the author, for there is not enough room to play out all the implications of the scenario Chiang posits. I also found Chiang’s writing to be much more stilted and summary than his usual seamless prose.

The other hard science fiction story nominated is Ted Chiang’s “The Lifecycle of Software Objects.” Usually if Chiang’s name is on a prize ballot, you can predict with confidence that he will be the winner, but I thought Chiang had a rare miss with this story of software pets, called digients, that develop personalities through interaction with their owners. Chiang poses a number of interesting ethical questions regarding what obligations, if any, humans might own to such creations; can you simply choose never again to boot up an artificial intelligence if you get tired of it? This is one case in which the novella length failed the author, for there is not enough room to play out all the implications of the scenario Chiang posits. I also found Chiang’s writing to be much more stilted and summary than his usual seamless prose.

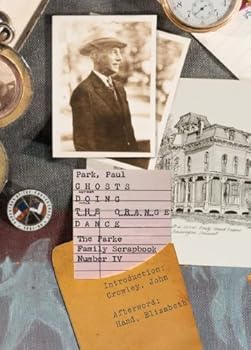

I think of myself as a fairly sophisticated reader, but I confess that my reaction upon completing Paul Park “Ghosts Doing the Orange Dance,” from the January/February issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction was, essentially, “Huh?” Much as I love metafiction – fiction about writers and writing and fiction itself – the point of this story completely escaped me. Set in 2019, this imaginary memoir of a future Park seems to portray a United States in serious decline, with energy largely unavailable and universities – and especially libraries – fallen largely into disuse. Park recounts a family history that includes at least a touch of the eerie, though nothing is ever completely spelled out. It’s as if Park deliberately set out to write an impenetrable novella. I like a difficult read as much as the next woman, but I prefer to be able to figure out what’s going on with a bit of close attention and effort; here, that effort was not rewarded. The story is literary, abstruse, and very strange. If you don’t mind not knowing what the heck is going on, this might be the story for you.

I think of myself as a fairly sophisticated reader, but I confess that my reaction upon completing Paul Park “Ghosts Doing the Orange Dance,” from the January/February issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction was, essentially, “Huh?” Much as I love metafiction – fiction about writers and writing and fiction itself – the point of this story completely escaped me. Set in 2019, this imaginary memoir of a future Park seems to portray a United States in serious decline, with energy largely unavailable and universities – and especially libraries – fallen largely into disuse. Park recounts a family history that includes at least a touch of the eerie, though nothing is ever completely spelled out. It’s as if Park deliberately set out to write an impenetrable novella. I like a difficult read as much as the next woman, but I prefer to be able to figure out what’s going on with a bit of close attention and effort; here, that effort was not rewarded. The story is literary, abstruse, and very strange. If you don’t mind not knowing what the heck is going on, this might be the story for you.

The other three novellas are all fantasies, and are all exquisite. The first is Rachel Swirsky’s “The Lady Who Plucked Red Flowers beneath the Queen’s Window,” about a sorceress, Naeva, whose queen – her lover – assassinates her. But it’s not a complete assassination; she can be recalled to a limited sort of life to give advice, first to her queen, then to those who follow. As the millennia go by, she is recalled less and less, but each time she faces a culture that has changed radically. Her own beliefs are abandoned by society almost immediately, but she is never persuaded that men are anything more than worms, and she stands by this principal even under the most dire circumstances. It is a strange form of immortality she has attained, and one she hates. Then, when the universe dies and is reborn, she is given a choice: continue or end? I loved this story as much as I hated – yet understood – Naeva. It’s hard to handle a broad sweep of time, as Swirsky does, but she does it well.

“The Alchemist,” by Paolo Bacigalupi, is a departure from hard science fiction into fantasy for this multiple award-winning author. It nonetheless shares with Bacigalupi’s science fiction a concern with the harm that humans can unthinkingly render on their environment by the use of energy. The difference is that in this story, the energy is magic instead of fossil fuels. In this universe, using magic causes bramble to grow – a terrible growth that overwhelms fields, streets, whole towns, and can barely be kept back by fire and ax. Worse, the spines of the bramble are extremely poisonous to humans, inducing a sleep from which the victim never awakens. The story is told in the first person by Jeoz, a man who used to be an artisan of beautiful things, and wealthy from it. Now he has turned alchemist, trying to find a way to beat the bramble without using magic. He succeeds in his quest, saving the life of his beloved daughter, Jiala, in the process. But that’s when the problems begin: when he takes his invention to the mayor and the mayor’s sorcerer, nothing but trouble follows. How Jeoz escapes, and what he does with his new technology, makes for an excellent story. If you’re interested, Kat has reviewed the audiobook version of this novella.

“The Alchemist,” by Paolo Bacigalupi, is a departure from hard science fiction into fantasy for this multiple award-winning author. It nonetheless shares with Bacigalupi’s science fiction a concern with the harm that humans can unthinkingly render on their environment by the use of energy. The difference is that in this story, the energy is magic instead of fossil fuels. In this universe, using magic causes bramble to grow – a terrible growth that overwhelms fields, streets, whole towns, and can barely be kept back by fire and ax. Worse, the spines of the bramble are extremely poisonous to humans, inducing a sleep from which the victim never awakens. The story is told in the first person by Jeoz, a man who used to be an artisan of beautiful things, and wealthy from it. Now he has turned alchemist, trying to find a way to beat the bramble without using magic. He succeeds in his quest, saving the life of his beloved daughter, Jiala, in the process. But that’s when the problems begin: when he takes his invention to the mayor and the mayor’s sorcerer, nothing but trouble follows. How Jeoz escapes, and what he does with his new technology, makes for an excellent story. If you’re interested, Kat has reviewed the audiobook version of this novella.

“Iron Shoes,” by J. Kathleen Cheney, is the first work I’ve read by this author, but it won’t be the last. This charming story, apparently set in the early days of the 20th century, is a love story at its heart, the only one of the nominated novellas to which that term can fairly be applied. Imogen Hawkes is a young woman whose husband has died, leaving her a horse farm that is mortgaged to the hilt. Although she has reached an agreement with her banker, that banker sells the debt to another banker who chooses to disregard it – all the better to gain Imogen’s hand in marriage, not to mention her farm, which adjoins his. If Imogen can’t pay the mortgage, she’ll have little choice but to consent to a marriage that is anathema to her. And her only hope for paying the mortgage is for her horse to win the Special Stakes.

Imogen’s father was a puca, her mother human; she has some small magic, but no control over it, and her mother raised her to be afraid of it. So when another puca arrives on her farm in the form of a new stallion, kept in that shape and controlled by the iron shoes nailed to his hooves, she believes nothing but trouble awaits. Still, she has too soft a heart to continue to torture the creature, and removes the shoes. In his human form, the puca is a charming and handsome man. The story proceeds from there, pretty much along the lines of a typical romance, but with the spice of magic added. I thought I’d outgrown romances, but this story convinces me otherwise.

And so: six excellent stories. I’ve had a wonderful week reading them all. I’m eager to see which one will win the Nebula.

Wonderful post. As a novella writer, I find the lack of a market frustrating to say the least. One would think that in the era of E-Books, novellas should make a forceful comeback.

At least I hope so.

I’m with you, Rafael. I think it’s a marvelously elegant form.

We should thank the market for giving us publishers like Subterranean and PS Publishing, who have been publishing novellas as free-standing books fairly regularly of late. They’re also gorgeous editions, usually.

I sure wish Bacigalupi would expand his message. An absolutely stunning writer, just seems to have one track mind when it comes to the message his stories convey.

Justin, “The Alchemist” didn’t have the bioterrorism feel that many of his other works have and, to be fair, many of his stories have that message because they’re set in the Windup world. (And even though I get tired of that theme, I still love Bacigalupi’s stories.)