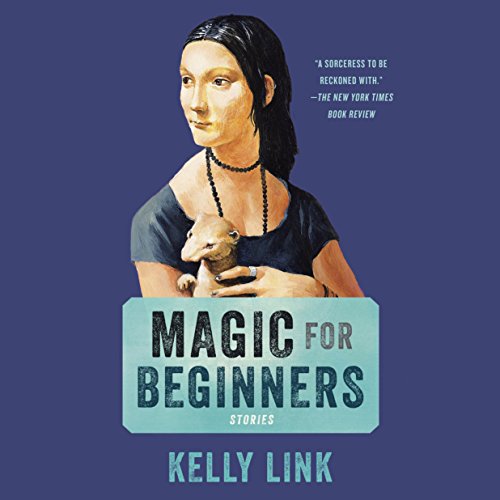

![]() Magic for Beginners by Kelly Link

Magic for Beginners by Kelly Link

Kelly Link’s short story collection, Magic for Beginners, is a great piece of work. In a bit of a departure from her earlier collection Stranger Things Happen, the stories in it don’t follow normative narrative structures; they draw from sources as various as fairy tales, kitchen sink realism, heist stories, TV fandom, and Link’s own surrealist vision. These nine stories don’t share overt connections, but they do provide a window into modern American life, complete with bland marriages, mortgages, and random zombie sightings. I listened to Random House Audio’s version of this book which is almost 11 hours long and is read by various actors such as Cassandra Campbell, Lorna Raver, Marc Bramhall, and others.

The first story, “The Faery Handbag,” was my favorite. It was the most straightforward, which probably indicates that I’m a lazy reader and not worthy of Kelly Link’s beautiful stories. But this story was just fun. The main character’s grandmother, Zofia, claims to be hundreds of years old, to come from a country no one’s ever heard of, and to have a handbag that contains an entire world. She cheats at scrabble and goes on dates with her ageless husband every 20 years and teaches her granddaughter phrases in Baldeziwurlekistanian (Link likes languages, especially made-up ones). When Zofia dies, the main character is charged with protecting the handbag — but it has disappeared. The reader, Rebecca Lowman, sounded just like what I imagined the protagonist would sound like — young, intelligent, earnest, and a bit sarcastic.

The third story, “The Cannon,” didn’t make any sense at all and I loved it. Written as a Q&A between two un-named characters, Link proceeds to tell us a lot about cannons, and one particular cannon in general, while using cannons as a metaphor for sex, marriage, and transcendence. Listening to this story was especially fun; two readers, Arthur Morey and Meera Simhan, took the parts of the questioner and the answer-er, and their delivery was so sly, funny, and naturalistic that, at times, I forgot I was listening to a discussion about a magical cannon. This passage, in particular, startled me into laughing out loud while I was listening at the gym: “Q: Who was the first person to be fired from a cannon? Was it a man or a woman? A: The first person to be fired from a cannon was a young man dressed as a woman.” I think this is a prime example of how, even when I have no idea what she’s talking about, Link can still tickle my funny-bone with her combination of surprising images and precise word choice. (And isn’t that, partly, the point?)

The fourth, “Stone Animals,” was less enjoyable for me, although it was impressive enough to win a place in 2005’s Best American Short Stories. It follows a family who has just moved into a house in the suburbs that is haunted by rabbits. Rabbits plague their yard, and their front walkway is flanged by two stone rabbit sculptures. (Link has confessed to watching Buffy compulsively and I have to wonder if the rabbit-haunting was inspired, in part, by Anya’s fear of bunnies.) As the story progresses, the family’s possessions appear strange, twisted, and wrong to them; they stop using toothbrushes, alarm clocks, washing machines, and even entire rooms as they succumb to the odd haunting. At the same time, it’s a rather mundane story about the slow breakdown of a marriage. But I found it too long and was thrown off at the beginning. It opens with an answer to a question that you don’t get to hear. “Henry asked a question. He was joking. ‘As a matter of fact,’ the real estate agent snapped, ‘it is.'” This was particularly confusing for me as a listener because Link doesn’t state the question. It wasn’t until I read a review of this story that I realized what the question was: “Is the house haunted?” In retrospect, I should have figured this out, but in the moment, I just didn’t get it — I kept rewinding, wondering what I had missed.

“Catskin,” the next story, tells the story of a witch, her children, and her cats. In this world, humans wear the skins of cats and witches cannot have children via biological means, but instead build their children out of twigs and leaves, etc. The protagonist, Small, is the witch’s youngest child and the heir to her “revenge.” I liked the fairy-tale atmosphere that Link creates; the story progresses through dream logic that, even when awake, makes a bent sort of sense. It reminded me a lot of Italo Calvino — Link even uses direct address from time to time. But I felt like the story went on too long, like mythological works such as The Mabinogion, which are episodic rather than having a concrete beginning, middle, and end. This was read by Marc Bramhall, who delivered both the humor and the otherworldliness well.

The volume’s sixth story, “Some Zombie Contingency Plans,” was a fun read, following an ex-con who crashes parties to meet women and carries around a stolen painting everywhere he goes. This story was a great example of Link’s ambiguous genre status. I listened to it with my fiancé, Wil, who does not enjoy reading speculative fiction as a rule. At the end, we both loved the story but had opposing interpretations of it based on our expectations. He listened to it as a realist piece, and concluded that it was told by an unreliable narrator, whereas I heard a spooky magical realist work. The fact that we could both love this story so much but have different interpretations of “what happened” is fascinating to me and speaks to Link’s skill and subtlety.

Finally, “Magic for Beginners” was another interesting, fun read that didn’t follow typical narrative structures. It tells the story of Jeremy, a high-schooler who watches a television show, “The Library,” with his group of friends. They enjoy debating its meaning and the identity of its main character, the ever-changing Fox. Link’s depiction of fandom is part of the fun of this story. But other things, seemingly unconnected to the TV show, are happening, too. Jeremy’s father has written a novel starring his son in which he dies from a brain tumor, while his mother has unexpectedly inherited an isolated phone booth and a Las Vegas wedding chapel. Link complicates the story further by insisting that Jeremy and his friends — indeed, the story we’ve just been reading — are also part of the TV show “The Library.” On the whole, I was captivated by the story, and especially loved the end when Jeremy and his mother visit the wedding chapel, which (hilariously) turns out to be cheesily horror-themed, like Disney’s Haunted Mansion. But I also felt like she was trying to do too much. The TV show, the wedding chapel, the blurring of reality and fiction — each would have made a great short story on its own, but together, it felt like too many elements.

Three other stories in Magic for Beginners — “Lull,” “The Great Divorce,” and “The Hortlak,” — were mostly boring to me. They each contained some interesting ideas, like prophetic pajamas and mediums as marriage counselors, but ultimately I didn’t really get them or just wanted to move to the next story.

Reading this volume challenged me in several ways. Yes, it was a difficult read, but it also challenged my ideas of what writing, and stories, should be. In a lot of ways, Link violates all the rules of writing as I’ve understood them. Her stories don’t have a beginning, middle, and an end. The events of the plot don’t always have a direct cause-and-effect relationship. It also made me question my taste. Why do I like Link, and not Paul Park? Even when I don’t get it, I have only undying admiration for her and her craft; but what is materially different, craft-wise, between what she’s doing and what Park tried to do with All Those Vanished Engines?

This conflict came into focus when I picked up the new paperback edition of Magic for Beginners, which includes a conversation between Joe Hill and Link. In it, the authors talk about the relative usefulness of interpretation, especially for stories that, like Link’s, are highly metaphorical and work to obscure their own meaning. Hill asks Link if art owes us explanations — and certainly, as a reader, I want them. As a reader, I generally want the story to be, in Link’s words, a “well-thought-out puzzle” that I can figure out. But maybe that’s the wrong thing to expect (all the time) from art. I also just like Link’s language. She makes me laugh. She puts images in my head that are beautiful, strange, and memorable. And she keeps me coming back for more, precisely because I don’t “get it” on the first… or second, or third… read.

My favorite was “The Faery Handbag” too, and my second favorite was the kids with the television show.

I didn’t really *get* “Stone Animals” but I thoroughly admired how she did it. That idea of the concrete world around you changing the second you look away, of things just not being *right,* is perfectly creepy.

I had heard about Link for years but only read her recently. I feel like I stumbled over a rock on the beach and it turned out to be a diamond.

I love the whimsy in her stories.