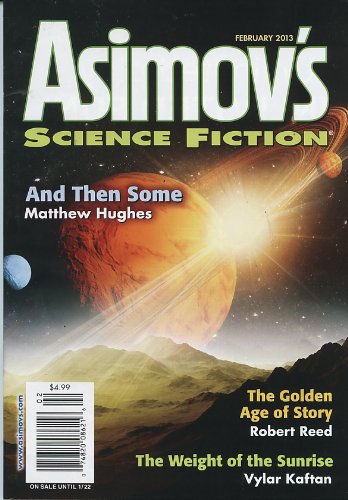

The February 2013 issue of Asimov’s is a delight from cover to cover. This time around, it’s the longer pieces that really given it is heft.

The February 2013 issue of Asimov’s is a delight from cover to cover. This time around, it’s the longer pieces that really given it is heft.

“The Weight of the Sunrise” by Vylar Kaftan is a fascinating alternate history novella that offers a pointed perspective on American history, serving as a sort of bookend to the recent film, “Lincoln.” Slavery was an evil obvious even to those who practiced human sacrifice and saw nothing wrong with incestuous marriages of royalty, as did the Incas, as Kaftan makes clear. Kaftan envisions an Incan civilization that has escaped the ravages of Spanish conquistadors with military cunning. Smallpox still troubles the Incas, though they have learned in this tale, unlike in life, to manage it through quarantine, thanks to the insight of a great physician. This makes it a strong and wealthy civilization in the 18th century when the Americans are planning for revolution. The Americans send an ambassador to the Incas to trade smallpox vaccine for an enormous amount of gold sufficient to fund their war against England. The ambassador speaks of the glorious country for which he and his countrymen struggle, one in which a man can make his own fortune based not on hereditary titles but on his own wits, free to do as he pleases. But he does not appear to hear the irony in his own words, spoken as his slave — clearly his half-brother — waits on him hand and foot. It’s a complex story narrated by an Inca who is lower caste royalty by virtue of having survived a smallpox outbreak, the translator for the Inca court. I’ve enjoyed some of Kaftan’s earlier fiction, including the Nebula-nominated “I’m Alive, I Love You, I’ll See You in Reno,” and she gets stronger with each new publication. She’s definitely a writer to watch.

Matthew Hughes has a new novelette set in his Ten Thousand Worlds milieu, in a time when Earth is dying because the sun has grown old — it’s reminiscent of Jack Vance’s Dying Earth. Hughes’s conceit is that, as the Earth dies, so does science, and magic will replace it. In “And Then Some,” Erm Kaslo is a man who solves problems — for a price. He arrives at a small community in an out-of-the-way solar system to serve a warrant. But the law enforcement officers there are corrupt, as Kaslo finds out the hard way when he wakes up a slave condemned to working a mine for an ore that he doesn’t recognize. It isn’t surprising that Kaslo finds his way out of this predicament, but the story doesn’t end there. Indeed, it gets much more interesting as we find out what can be done with that ore. Hughes has been constructing a fascinating universe for years now, and each new entry gets slotted into a future history as complex as anything invented by Heinlein or Asimov, with the same sort of straightforward, no frills writing.

“The New Guys Always Work Overtime” is a sort of time travel story by David Erik Nelson. A factory brings in workers each week through a portal, where the narrator meets them to give them their human resources orientation. The workers usually come from a time and place where the pay is low and the work especially onerous, and they find the minimum wage the factory is willing to pay them to be a generous bonus. These workers aren’t just snatched up without a by-your-leave; they are recruited from their own time. Whether they’re miners who get a break from the black-lung-inducing methods of the early 20th century or cowboys from the Wild West, they’re generally good workers and demand a lot less than do present day employees. But one day, the portal spits out a group of workers who are unusually scrawny with hollow eyes, and it’s immediately plain where they come from even if the narrator doesn’t see their tattoos and they don’t wear yellow Stars of David. A moral dilemma now confronts the narrator; can he really send the woman who has asked for “gift” for her return back to Auschwitz II-Birkenau, from which she hales? (“Gift” means “poison” in German.) The story that starts out as an amusing play on today’s multinational corporations gets very serious very fast.

Another strong story comes from M. Bennardo: “Outbound from Put-in-Bay.” It’s about a world in which global climate change has had its way with us, and all but drained the Great Lakes. Civilization has taken a hard hit, and the United States has broken apart into multiple countries. Canada has become the primary source for crude oil, and a group of smugglers on what remains of Lake Erie in the Republic of Erie make their livings picking up barrels of the stuff dropped by their Canadian counterparts. It’s dangerous work, but the narrator, a woman with almost no money to her name but a crack shot with a rifle, scratches out a living serving as security for one particular smuggler. Her epiphany comes after a particularly tough winter run. I’m curious about what she does next in this world, which seems far too complex to warrant just a single short story. I hope Bennardo gives us more.

Robert Reed is a reliable writer of good stories, and “The Golden Age of Story” is no exception. It’s a tale of a new pharmaceutical combination that adds 20 percentage points to one’s IQ and also increases one’s creativity and emotional stability. But there’s a dangerous side effect: an ability, indeed, a compulsion, to sling “[c]ompulsive, highly imaginative bullshit,” as one customer in the sales business explains it. The drug is illegal, but it spreads quickly. Reed plays out the effects of this ability to lie well and creatively, demonstrating ably how much we depend on the fundamental honesty of most people in order to have a functioning society.

John Chu’s “Best of All Possible Worlds” features an alien who can make complete scores of the narrator’s favorite musicals play in his head in all their glory. This is a fine quality for a friend to have, but everything goes awry when the alien comes under attack and must protect the narrator. This “protection” projects the narrator into the world of the musical he’s been experiencing — “Candide” — and puts him in mortal danger, as the musical is now his reality, not a stage production. It’s a short, funny piece.

The poetry rewards rereading. Ruth Berman’s “How Many” didn’t make sense the first time I read it, but when I went back to it, now knowing its theme, it danced. Bruce Boston’s “Curse of the Procrustean’s Wife” uses mythology to tell a story about an abusive marriage. Robert Frazier’s “7:17 AM, June 30, 1908, Central Siberia” seems like a bit of found poetry cobbled together from the observations of those who saw the Tunguska Comet hit the earth.

Rounding out the issue are Paul Di Filippo’s book reviews of some of the more out-of-the-way offerings in the field, Sheila Williams’s editorial about time travel, James Patrick Kelly’s nostalgia about the early days of personal computers, and Robert Silverberg’s musings on Atlantis round out the issue.

Don't know how to answer that, Andrew; I've only read the long. But when it comes to REH, more is…

Would you recommend the long or the short version of Three Bladed Doom?

"A Gent From Bear Creek," originally a collection of short stories later cobbled together to make a novel, and "Three-Bladed…

What were the 4 novels we wrote? Two were Almuric and Hour of the Dragon, what's the other 2?

He has a new one just out (or being released soon) called DRILL. I'm interested, but I may need to…