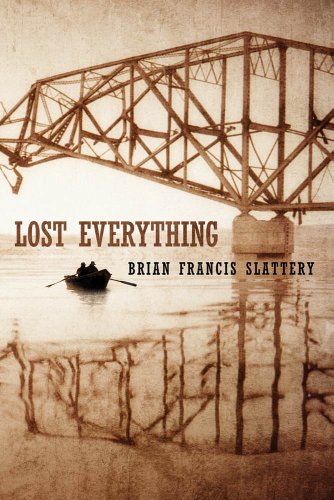

![]() Lost Everything by Brian Francis Slattery

Lost Everything by Brian Francis Slattery

Lost Everything, by Brian Francis Slattery, is a surprisingly small-bore and quiet post-apocalyptic novel. Where many deal with destruction on a country-wide or global scale and follow near-epic quests by some doomed or maybe-doomed survivors, Slattery takes his characters through a just-as-ravaged countryside but it all seems a little more domestic than the usual sort of end-of-the-world tale, a twist that is both the book’s strength and its weakness.

The world has seemingly been in the grips of ecological disaster, prompted one assumes by global warming, so that sea levels have risen and rivers have slipped their human bonds and wreaked havoc. At some point, the United States collapsed as a government and in this region at least — along the Susquehanna River between Three Mile Island/Harrisburg and Binghamton NY — war has broken out between two factions. This is all laid out efficiently, concisely, almost with the sense of elegy, by the unnamed narrator who is seemingly researching this story:

Do you see? How the world is now? Nobody can quite say how it came to be this way. There is too much. There is not enough. It started generations ago, and so much has been lost, and even all that I found does not help… Our great-grandparents told our grandparents that things were different once, when they were children. A little colder. Simpler. Not as many people were dying… There must have been a day, a single day, when it was too late, when we could not go back, but nobody can remember when it was. Do you see? The story I have left to tell is so small, of the people who stayed when everyone else fled. Two men going upriver to get a boy.

The river is our path through the novel, as this is sort of an anti-Huck Finn novel, the connection made clear not simply by the river as the main guide but by the protagonist’s name — Sunny Jim, as well as by their mode of travel — the old Mark Twain kind of riverboat. We don’t know much about what is happening out in the larger world, or even the larger country beside this relatively small region, save for one large exception. That exception is the “Big One,” an unbelievable (literally so for several characters) massive storm that is heading their way from out of the West, a storm that has achieved mythic and spiritual status and one that has choked off all communication with anyone in its wake, if indeed there is anyone left in its wake.

The human equivalent of the storm, for Jim, is the army moving up from the south. His wife had been a major figure in the resistance, while Jim had barely been involved. Somehow, though, he’s been labeled a resistance leader of some importance and so is targeted for removal. While the army moves up slowly behind him, it sends out two more quickly moving hunters: one is a squad trying to beat Sunny Jim to Binghamton and the other is a single woman, Sergeant Foote, trying to chase him down from behind.

Caught between the encroaching army behind him and the oncoming storm before him, Sunny Jim, joined by his friend Reverend Bauxite, races against time to head upriver and reach his son Aaron, whom he sent to his sister Merry in Binghamton to get him out of the war, this after his wife had been killed, a death Sunny Jim has yet to fully accept.

The story shifts amongst these characters — Sunny, Bauxite, Foote, the army squad, and various others Sunny encounters along the way. It also shifts back and forth in time as we follow these characters not only on their present journey but also are offered their backstories, showing how they got to this point in their lives. In many ways, Lost Everything is structured like the waterway at its center, flowing in one major direction but with all sorts of smaller tributaries feeding into it. And, like the river, some of its components are still as a quiet pool or lake while others are as fast and perilous as the floodwaters raging in.

Lost Everything is punctuated here and there by moments of stark violence, gun battles, massacres, atrocities. And also with moments of quiet human beauty and celebration, banjo music in the night, tenderness toward the orphaned or wounded. And behind it all always lies a destroyed world. But Slattery’s apocalyptic landscape isn’t the burned off radioactive wastelands or sprawling ruins that are common to the post-apocalyptic genre. Instead we get the wreckage of suburbia, exurbia, and downtowns. No huge skeletal skyscrapers or broken-off Statues of Liberty or drowned Washington Monuments. Instead we get small-town domestic ruins: the hulks of two-bedroom houses, abandoned cars, sagging basketball hoops, crumbling sidewalks. We get “Garages, open, patrolled by feral cats. Front yards littered with cardboard boxes, sagging suitcases, picture frames, instrument cases.” The ruins are of lives, not institutions.

There is lots of tension built into the story — Foote hunting Sunny Jim aboard the riverboat, the squad racing to be in Binghamton before him, the rain steadily increasing as the Big One nears, rumors of war behind and before them, the question of whether Jim will save his son, can his sister Merry protect him if Jim gets there late. The tension is heightened by the moments of random violence they encounter — fights breaking out aboard ship, attacks by bandits, a running game of Russian roulette.

But Lost Everything aims for much more than simply narrative suspense. With its sharp focus on a handful of characters and the way it examines their past lives, past relationships, past decisions, as well as the way it gives us insight into their hope and/or despair about the future, it is a more character-driven story than a plot-driven one — one that, though it has a basic storyline, meanders at a more leisurely pace. This is what I was referring to when I called its more quiet nature both strength and weakness. Some will find that meandering overly slow, I’m guessing, and will want to just cut through all or most of these backstories and relationship stories and get back to the gunfights and chase scenes. Personally, while I did think there were a few pacing issues, I felt myself thoroughly immersed in the elegiac, introspective nature of the story and was mostly content to let it carry me wherever the story drifted.

Give Lost Everything 70 or so pages. If you find yourself impatient, it’s probably not going to be for you, as the start is more linear and focused than the rest. But if you don’t mind the narrator’s digressions, the more poetic passages and moments of stillness, settle in and enjoy yourself. You’ll be well rewarded.

~Bill Capossere

![]() What will happen to America as the effects of global warming continue to wreak havoc? Brian Francis Slattery imagines a much different country in Lost Everything, which has been nominated for a Philip K. Dick Award for 2012 for the best paperback original novel. Slattery imagines that the country we know as the United States is gone, replaced by smaller, regional countries that are engaged in civil war. The Susquehanna River Valley is in the middle of such a war, about which we are told little save that it is ravaging the land and the people. Sunny Jim has lost his wife Aline to the war — not as a victim, but as a saboteur who died by her own bomb. Down the Susquehanna paddle Sunny Jim and the Reverend Bauxite, for Sunny Jim refuses to fight. They are trying to reach Sunny Jim’s sister and his son. They must do so quickly, before the Big One hits — a storm so severe that it leaves nothing in its wake at all:

What will happen to America as the effects of global warming continue to wreak havoc? Brian Francis Slattery imagines a much different country in Lost Everything, which has been nominated for a Philip K. Dick Award for 2012 for the best paperback original novel. Slattery imagines that the country we know as the United States is gone, replaced by smaller, regional countries that are engaged in civil war. The Susquehanna River Valley is in the middle of such a war, about which we are told little save that it is ravaging the land and the people. Sunny Jim has lost his wife Aline to the war — not as a victim, but as a saboteur who died by her own bomb. Down the Susquehanna paddle Sunny Jim and the Reverend Bauxite, for Sunny Jim refuses to fight. They are trying to reach Sunny Jim’s sister and his son. They must do so quickly, before the Big One hits — a storm so severe that it leaves nothing in its wake at all:

Just a boiling wall of clouds, gray and green and sparked with red lightning, and underneath it, a curtain of flying black rain, rippling with wild wind from one end of the earth to the other… I watched it take a town in the valley, far away below, and it was as though a wave were rolling across the ground, lifting houses, roads, trees, and all — anything that was still there — up into the air, into the mouth of the storm.

Along the banks of the river are communities that have suffered from both flooding and the war. Sandbags are piled to keep the river back, but over them the boaters can see smoke from gasoline fires and hear grieving families wailing over their dead. Some days the river banks instead offer markets, capitalism rising from the ashes. But soldiers swarm over the markets, and Jim and the Reverend are wary of getting on the highway instead of sticking to the river. When they hear about the Carthage, a ferryboat headed up the river, though, they decide to take the risk of going overland long enough to catch the boat.

The Carthage is a traveling menagerie: horses, camels, cows, birds, monkeys all over the deck. It’s full of people, too, with a band playing belowdecks, squeezing out room among the heavy furniture, the fabric, all the belongings of those who have taken to the river. The captain agrees to take Sunny Jim because she knew his wife, long before she met Sunny Jim.

And so this peculiar book hits its stride, telling of the adventures of those on the boat as it heads upriver. The parallels to Mark Twain’s masterpiece, Huckleberry Finn, are unmistakable: both books depict people escaping unbearable conditions (slavery for Twain’s Jim, drafting into the army for Slattery’s Sunny Jim) and using a river for their travel. But there are also differences: Sunny Jim and Reverend Bauxite travel north, not south; they ride against the current instead of with it; and they are passengers on a riverboat with the company of others, not a raft by themselves. Despite the violence both behind and before the travelers, the book is oddly quiet and elegiacal, a mourning for the loss of a better world and an inability to see any future. Indeed, the only future possible seems to be one of the world starting over once the Big One has scrubbed the face of the earth clean.

It’s easy to see why the Philip K. Dick Award judges’ panel chose Lost Everything. The book has a lot of strangeness to it, even in the manner in which it is told (there is a first person narrator who appears every now and then to address the readers directly for a few paragraphs, without us ever finding out much about this individual or how he or she fits into the story). And it is beautifully written, with vivid descriptions of people, places, weather, and horrific violence. But while I appreciate this book, I do not like it. The characters are not very likeable or particularly interesting. Despite the war, the river, the weather, little happens, and nothing is resolved. Perhaps Slattery was seeking to write a meditation on T.S. Eliot’s famous concluding line to “The Hollow Men,” in which the world ends “not with a bang, but a whimper.” In the end, what I’m left with is an appreciation of Slattery’s talent, and a hope that his next book will be more to my liking.

~Terry Weyna

It's hardly a private conversation, Becky. You're welcome to add your 2 cents anytime!

If the state of the arts puzzles you, and you wonder why so many novels are "retellings" and formulaic rework,…

I picked my copy up last week and I can't wait to finish my current book and get started! I…

Gentlemen, I concur! (Forgive me for jumping into your convo)

The cover is amazing. I love how the graphic novel (and the review!) hewed close to the theme of "good…