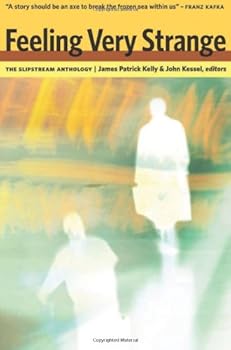

![]() Feeling Very Strange: The Slipstream Anthology edited by James Patrick Kelly & John Kessel

Feeling Very Strange: The Slipstream Anthology edited by James Patrick Kelly & John Kessel

Is there really any difference between post-modernism, interstitial fiction, slipstream and New Weird? Does anyone know? James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel try to outline the boundaries of slipstream with their anthology, Feeling Very Strange: The Slipstream Anthology, particularly by including a learned introduction and excerpts from a discussion that took place on the subject on a blog a few years ago. Ultimately, like so many things literary, from science fiction to erotica, it comes down to this: slipstream is what I’m pointing to when I say “slipstream.” Yes, there are a few defining features. It’s fantastic rather than science fictional. It is often surreal, and almost always postmodern in its sensibility. Bruce Sterling, who coined the term “slipstream” in an essay in a remarkable but short-lived journal called SF Eye in 1989, probably gave it the best definition anyone has come up with yet when he said that it is fiction “which simply makes you feel very strange.” And hence the title of this anthology, full of stories that will make you feel very strange indeed.

The story that scares and fascinates me the most in this collection is Ted Chiang’s “Hell is the Absence of God.” Chiang won both the Hugo and the Nebula in 2002 for this novelette, which is “the story of a man named Neil Fisk, and how he came to love God.” Fisk’s universe is one in which visitations by angels occur with the frequency of other sorts of acts of God, wreaking both havoc and death and the occasional miracle or miraculous cure. If one is caught in a shaft of Heaven’s light when the angel departs, one automatically becomes a pure devotee of God, and is ensured of salvation. In this universe, one can also see Hell on occasion; the ground becomes transparent, and those on earth can see the souls interacting just as they did on earth, except that they are forever separated from God.

Fisk loses his wife in an angelic visitation, and his life is thrown into chaos. He cannot love God, even though he knows that he will forever be separated from his wife if he cannot find a way to get to heaven. Indeed, he resents God for taking his Sarah away from him. What is he to do? How does faith work in this universe? How does he force himself not to believe — belief is a no-brainer in this universe, where God is manifest every day – but to love? He can’t love God merely as a means to an end, because that doesn’t work. He has to actually be devoted to God. How can Fisk develop true faith when he has none?

Chiang is one of the most gifted writers working today, regardless of how you categorize his fiction. “Hell is the Absence of God” should have the widest possible audience. This story alone is worth the price of the book.

Another worthy contribution to the book is Jeffrey Ford’s “Bright Morning,” a surreal piece based on a lost Kafka story that the narrator read in high school and could never find again. Kafka scholars swore it didn’t exist. The narrator — who sounds very much like Jeffrey Ford himself, particularly when he becomes a fantasy writer whose writing is frequently compared to Kafka’s — spends years searching for the lost story. The question is: when it comes right down to it, does he really want it? Ford is one of my favorite writers, and this tale didn’t disappoint my high expectations.

Theodora Goss contributes “The Rose in Twelve Petals,” the story most easily defined as post-modern. This retelling of Sleeping Beauty in numerous parts, in numerous times, from numerous points of view, is deliciously ironic.

Jonathan Lethem’s “Light and the Sufferer” is one of those stories that throws you into an odd situation and explains things only very gradually, so that you are bewildered as you rollick along with events — and the events here come at you very fast. The alien species that follows the protagonist and his brother is there to protect them, isn’t he? Or is he there for the drugs? Or is there another reason for his presence? Who can understand what the aliens are after? In fact, who can understand what one’s own brother is up to? Can we ever understand one another?

“Sea Oak” by George Saunders is about an extended family just trying to get along, even after the matriarch, Aunt Bernie, dies. Aunt Bernie doesn’t go peacefully, though; after having been the peacemaker all her life, she decides to get some of her own back after her death. And yes, panic ensues. This is one of the funniest and weirdest stories you’ll ever read.

The collection also includes the much-lauded story “The Specialist’s Hat” by Kelly Link. However, even though I’ve read it three times, I still don’t understand its appeal. There must be some symbolism here that I’m not getting. I understand that it’s about children in jeopardy from a very odd babysitter, that it’s about death, and so on, but the whole thing with the two children and the babysitter riding a bicycle in the attic and wearing what the babysitter calls “the specialist’s hat” just does nothing for me, even if they have to climb up the chimney to get to the attic. Feel free to tell me what I’m missing in the comments section.

There are many other wonderful stories in this collection, including a beautifully odd little number by Jeff VanderMeer, “Exhibit H: Torn Pages Discovered in the Vest Pocket of an Unidentified Tourist”; “The God of Dark Laughter” by Michael Chabon; and a story by M. Rickert entitled “You Have Never Been Here.” There are also good stories by Bruce Sterling, Aimee Bender, Karen Joy Fowler, Benjamin Rosenbaum and Howard Waldrop.

My only complaint with the anthology is the editors’ choice to reproduce excerpts from the comments section of David Moles’s blog, Chrononautic Log. Transcripts of blog discussions are about as interesting as transcripts of conversations; while they are often fascinating while they are going on, they lose something when they are reproduced years later. The ideas may remain fascinating, but they are usually undeveloped in blog format and not as useful or interesting as later essays or blog posts by the participants when they have contributed greater thought to the subject. A series of posts on whether slipstream would better be called infernocrusher fiction, for instance, is just silly. Perhaps this is more fun for industry insiders than for those of us for whom this was our first exposure to the Chrononautic Log.

I spent many strange hours reading this book. I feel strange writing about it. I expect to wake up as a giant cockroach tomorrow morning. Can anything really be better than that?

Great review–thanks for the direction.