Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland & Through the Looking Glass by Lewis Carroll

When Charles Ludwig Dodgson first began to tell the story of Alice’s adventures underground to the three Liddell sisters, he had no idea whatsoever the impact that his work would one day have in the cultural history of humanity. Is there a person alive in Western civilization that doesn’t know of Alice, the Mad Hatter, the Queen of Hearts, the White Rabbit and the Cheshire Cat? I seriously doubt it. Writing under the pen name of Lewis Carroll, Dodgson’s quirky fairytale soon became a publishing sensation in Victorian England, quite an unusual feat for a dour mathematician who had no interest whatsoever in boys, women or most other human beings, and instead lavishing his attention on little girls — particularly one Alice Liddell, to whom he presented the original manuscript to. The story of Lewis Carroll is just as fascinating as his fictional Alice, so I would suggest following up the Alice books with a good Carroll biography.

In a story that is so random (basically made up of one little girl wandering about in a dream) there is plenty of room for all sorts of crazy theories as to exactly what everything means. Does Alice have a deep subtext, filled with hidden meaning and messages? Is it Freudian? Elaborate satire? Does it reflect the deep internal frustrations, anxieties and wish-fulfillment of a slightly-disturbed mathematician obsessed with little girls? Or is it simply a series of weird and wonderful events dreamed up for the enjoyment of children? The fact that nobody is really sure what to make of this story is probably the reason why it’s still published, read and discussed today.

The other reason is its historical value. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was the first book designed for children that was entirely void of any sort of moral, and instead written solely for pure entertainment purposes. Before Alice, children were stuck with stories that preached goodliness and virtue, something that Carroll himself pokes fun at during the course of the story, when he refers to “several nice little stories about children who had got burnt, and eaten up by wild beasts, and other unpleasant things, all because they would not remember the simple rules their friends had told them.” His stories came like an unexpected breath of fresh air amongst Victorian society, and it was little wonder that adults as well as children helped to make Alice a bestseller during its day.

Another crucial feature to the tale is Alice herself, often considered the first realistic representation of a child in literature. She’s curious, but sometimes a little shy. She’s polite, but manners often give way to frustration and temper tantrums. She’s intelligent, but not as intelligent as she would like to think she is (relying heavily on an education that often fails her). She often holds her own against the contradictory natures of the people she meets, but more often than not is baffled and belittled by them. She possesses some degree of common sense, but often does some remarkably stupid things. She’s likeable, but she’s also a bit of a show-off and a snob. In other words, she’s the first (and perhaps the best) example of a three-dimensional child character in literature geared toward either children or adults.

Alice in Wonderland begins with the infamous sight of a white rabbit with a waistcoat and pocket-watch muttering to himself: “I’m late! I’m late!” Abandoning her sister and the dull book that she’s reading, Alice follows the rabbit down a rabbit hole and unexpectedly finds herself drifting deep down underground. What follows is a series of weird and wonderful meetings with the likes of the Queen of Hearts, the Mad Hatter and the March Hare, the Cheshire Cat and the Gryphon and the Mock Turtle, as poor Alice — the only sane person in the madhouse — struggles to make herself heard against this twisted parody of the adult world.

Nearly every page contains a clever pun, nonsensical poem or mathematical puzzle, and there’s plenty here to keep you fascinated, whether it be Alice’s abrupt shrinking and growing (brought on by eating Wonderland food, and perhaps reflecting Carroll’s desire to control the growth of his young protagonist), the beautiful garden that Alice cannot seem to reach (and when she does, she finds it not quite to her liking, perhaps suggesting a reverse-Eden, in which children desiring adulthood soon realize that it’s not quite what they expected it to be) or Alice’s internal crisis in which she debates whether the surreal circumstances she’s found herself in have resulted in her loosing her own identity (I won’t even try to open the jar on that one!) No wonder scholars can go mad trying to untangle this tale! Even the fact that the story succumbs to the ultimate cliché in fantasy-fiction, the ending that will reward you with an F if you use it in a creative-writing exercise at school (I am of course, referring to the fact that Alice wakes up at the conclusion of the story to find that it was just a dream), doesn’t damage the power of Carroll’s imaginative force.

Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There is a little more structured in terms of its storyline, perhaps because Carroll was not simply making most of it up on the spot, as he had done with its predecessor. This time, when Alice falls asleep, she crawls through the mirror on the top of the mantelpiece and into the room on the other side. There she finds a land organized into the shape of a giant chessboard, in which Alice herself is a little pawn that must journey to the end of the board if she wishes to become a Queen. On the way she meets several chess pieces, including the Red and White Queen, and the White Knight (widely believed to represent Carroll himself), as well as Tweedledum and Tweedledee, Humpty Dumpty, a garden of living flowers, and the Lion and the Unicorn, the latter of whom famously tells Alice: “If you’ll believe in me, I’ll believe in you.” My favourite chapter would have to be the one that involves the ludicrously pompous Humpty Dumpty (who is really the one who coined the term “un-birthday”, not the Mad Hatter and the March Hare as the Disney version would have you believe), though equally memorable is the intriguing episode when Alice happens upon the sleeping Red King, and is told that he’s dreaming of her. Is Alice in the Red King’s dream, or is the Red King in Alice’s dream? What should happen if one of them should wake up before the other? It’s a disturbing metaphysical conundrum, and hints at the depths with which a scholar (or deep-thinking child) could delve into these stories.

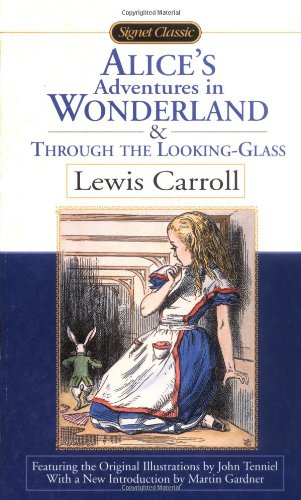

Of course, not every child will enjoy the “Alice” stories. What was once vividly imaginative and innovative for a stifled Victorian audience has long since become commonplace in children’s fiction, and the randomness with which the adventures take place can often unsettle young listeners (as they certainly did me, as I always felt that Alice was caught inside a nightmare). However, others will delight in the madness that abounds throughout the story, and others still will learn to appreciate the work as they get older. There are hundreds of editions out there, most probably quite as good as the next, but I would encourage buyers to track down an edition with John Tenniel’s famous illustrations — you simply cannot read the Alice books when they are not accompanied by Tenniel’s portrayal of his demure little Alice, with her hooded eyes and large forehead. It would be like reading C.S. Lewis without Pauline Baynes, or Roald Dahl without Quentin Blake. Unthinkable!

~Rebecca Fisher

I love Lewis Carroll’s imagination and sense of humor.

I love Lewis Carroll’s imagination and sense of humor.

The audio version read by Jim Dale (Listening Library) is superb.

~Kat Hooper

Don't know how to answer that, Andrew; I've only read the long. But when it comes to REH, more is…

Would you recommend the long or the short version of Three Bladed Doom?

"A Gent From Bear Creek," originally a collection of short stories later cobbled together to make a novel, and "Three-Bladed…

What were the 4 novels we wrote? Two were Almuric and Hour of the Dragon, what's the other 2?

He has a new one just out (or being released soon) called DRILL. I'm interested, but I may need to…