This week K.M. McKinley, author of The Iron Ship, stops by to answer some questions about her fascinating debut novel set in a quasi-industrial world and centered on a quintet of siblings. It’s a book you’ll want to pick up, so read on to learn how it came about. We’ll be giving away a copy of The Iron Ship to one random commenter with a U.S. address.

Bill Capossere: One of the aspects I liked quite a bit about The Iron Ship was that we were presented with a world with a clear sense of a future via industrial/technological momentum but also with a sense of deep history thanks to the references to the two fallen civilizations and the loss of the gods. Can you speak a bit to your construction of that time setting — what you were going for and why, how much of the history is in the book versus how much you sketched out (or more fully detailed) for your own purposes, etc.?

K.M. McKinley: I love fantasy; it was the first literary genre I fell for. But I find a lot of it overly formulaic. This isn’t a criticism necessarily; fantasy is escapism, there’s a knack to creating a streamlined, almost fairy-tale for adults, but that’s not the kind of world I like. I read on the net an article called “You know you are in epic fantasy when…” and one of the signifiers was “you live in a kingdom with no major exports, or economy of any kind”, or something like that. That’s a problem I have with a lot of it.

I like what I call “whole cloth” worlds, worlds that seem to be real, with loads going on in them. Pretty much like our world. I won’t say I sketched everything out, because I didn’t, and I won’t say there’s a ton of notes (although there is plenty that will make it into the next volume). But I think I’ve constructed it in such a way that, if you asked me what Macer Lesser was like, I could invent it and it would look like I always knew. A lot of setting a world up like the one in The Iron Ship is leaving many threads dangling, and having an idea where they lead even if you aren’t entirely sure. It’s all a big confidence trick!

The reader has a lot thrown at them — different types of magic apparently (witches, mages, magisters, Tyn magic, death magic), different races, different species, sub-categories, fallen gods, etc. A lot of these elements come without much immediate explanation. It sounds like this was conscious choice on your part. Did you have any concerns about readers feeling a bit, um, “at sea”? Will we gradually learn more specifics about events or how things work in this world (for instance, that intriguing story about the gods being driven out) or will some things just remain a mystery?

The reader has a lot thrown at them — different types of magic apparently (witches, mages, magisters, Tyn magic, death magic), different races, different species, sub-categories, fallen gods, etc. A lot of these elements come without much immediate explanation. It sounds like this was conscious choice on your part. Did you have any concerns about readers feeling a bit, um, “at sea”? Will we gradually learn more specifics about events or how things work in this world (for instance, that intriguing story about the gods being driven out) or will some things just remain a mystery?

I’m not a fan of didactic fiction where the author sets out his entire world from beginning to end, explaining everything, or worlds where one element alone is painstakingly described. I’m thinking of fantasy with intricate magic systems but no real social reality to them. Again, it can work; it’s just not my preference.

But this is the danger of a whole cloth world — in trying for verisimilitude, you can put readers off, because some readers do want every detail laid out. That’s fine, The Iron Ship won’t be for everybody.

As I’ve tried to make the characters feel real, their world needs to feel real. We are ignorant of much about our own lives. Most people in the West don’t know the basic industrial processes that underpin our culture, or even where our food comes from. For example, I don’t know the provenance of the coffee I drink every day beyond the very broadest terms. If I were to follow it from plant to pot the story would be full of surprises, but I don’t need to know that to live my life. Or to drink coffee. Most contemporary tales don’t go into that kind of detail. The level of detail in The Iron Ship is the same. It’s what the characters do that matters.

On saying that several of the things you mention in fact, will prove to be very important parts of the plot, and most will be at least touched on. On the whole I prefer to explain things in places where it is natural to do so, otherwise a world like this could engender a book that was wall-to-wall infodump, and that’s no good!

It’s a difficult balancing act, I admit. I probably don’t get it right all the time.

Some of the material reminded me of actual history — the title vessel, for instance, called to mind the Great Eastern and its construction, the early industries/crafts felt fully realized in terms of their actual workings and methods, and one character had a sort of Tycho Brahe/Kepler mash-up feel to her. Are there direct historical analogues to events and characters in The Iron Ship? Inspirations? What sort of research did you do in preparation for the novel?

There are a lot of historical elements in The Iron Ship. I did draw on the construction of the Great Eastern (the accident is inspired by a real event there). The industries and the social upheaval are rooted in reality, while the countess is inspired by every woman in history who decided not to toe the line — from Anna Comnena to Emiline Pankhurst.

I did not do a great deal of research specifically for the book. I’ve always been interested in history — I had little choice, my parents are very big on it. They dragged me around every historical site, and in the UK we have a great many. I have a history degree, and a lot of it I’ve absorbed over the years. But I did read a fair bit about specifics, like nautical steam engines, and industrial processes. Ironically, I used to find early modern and early industrial history stultifying, but it’s come to fascinate me, and I use it extensively in this book.

I used the word “sprawling” to describe The Iron Ship in my review, and it certainly covers a lot of ground in terms of plot and characters. With such a large family at the core, and each getting their own story to some extent, this was almost unavoidably going to be the case. Did you have any difficulty juggling storylines or characters or worry some might be lost in the shuffle? Any particular methods for keeping track of them? And will those who may have gotten a bit less page time here (Garten for instance) get more in the future?

I use Scrivener. That’s great for moving chunks of story around. To begin with, I created dozens of sub documents in folders named for the characters, just titles of scenes, and moved them about until the character’s chronology was sorted. Then I wrote great tracts of some of the character’s plots as if they were each discrete stories. I then broke them up and interleaved them, altering their position for pacing.

Most of the characters you meet in the first book you’ll see again, even ones who have only fleeting appearances. I’m inspired by A SONG OF ICE AND FIRE in this — in our world there are a lot of people, and all our lives intersect. We don’t exist in a vacuum, so neither do these characters. But I don’t intend to introduce vast numbers of characters in every book.

Some did suffer a bit, Garten being the prime example. But he does have one of the biggest roles in book two, if that helps!

Staying on characters for a bit. One of the aspects of the fantasy genre that I find so powerful is the way metaphor can become reality. One of your characters struggles apparently with depression and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (are those fair characterizations?) and while in our world we might say metaphorically he is struggling “with his demons,” in fantasy those “demons” can become frighteningly real. On the one hand, story-wise this simply adds a nice bit of tension to your story. But it could also, it seems to me, be a way to explore this issue in some substantive, if somewhat removed, fashion. Can you talk about your decision to have a character facing these problems?

I suffered from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder from the age of 14 until only a few years ago, when I was around 35. For twenty years, I was living a double life. On the surface, I was normal (ish) and happy and perhaps even carefree, but underneath I was in constant, irrational fear that ramped up to terror.

What you say is exactly so — Guis is struggling with his demons, literally. One thing I wanted to do with this book was to draw on and explore my own experiences. I’m from a large family, I used to be genuinely crazy. They’re both in there.

I did get better, which is somewhat unusual, to the point where I think I can safely say I’m completely cured. The human brain is amazingly plastic. I’m fortunate.

Meanwhile, several of the female characters have an outer rather than an inner struggle, dealing with the frustration of being smart, competent women in a society that sees little worth in women. What I particularly liked is that rather than toss them all in the same boat, treating them as interchangeable “Women Oppressed By Society” character types, each of them has her own sort of expertise (rather than being the abstract Competent Woman Type) and despite having the same problem, deals with it in her own unique fashion. Was this sort of thread/theme important to you as a writer going into the novel — did you decide early on to highlight this idea of women taking charge of their own lives, or is it just the natural outgrowth of a setting with a society on the cusp of major change, including the changing role of women?

I very much intended to address the role of women in genre fiction. Too often they’re there for fridging, to motivate male characters. ‘Strong female characters’ frequently means women who are basically men — swearing and fighting, dragging a hopeless boyfriend along behind them. These characters can be cool, even subversive, although too many are male wish fulfilment.

The issue is that there’s not much range to female characters. I know plenty of competent women with all manner of skills — lawyers, teachers, engineers, scientists, surgeons. I don’t know many foul-mouthed intergalactic she-devils. By the same token, you could say I don’t know any men like Wolverine either. And I don’t, but clichéd male characters are afforded a broader scope than clichéd female ones.

Another irritation, in fantasy in particular, are women doing as they please with no hindrance, in worlds that the author has set up as stringent patriarchies. That’s lazy. How people beat the cultural odds is the interesting part of the story we rarely get to see.

I wanted to depict women in such a situation, who are restricted by it but who still manage to exercise their will. Most women can give you an example of day-to-day sexism right now. That’s shitty, but they still succeed in spite of it. We’re massively sensitised to this issue, and to the good because it means it’ll eventually get dealt with. But at the same time our outrage perversely robs women of power — we assume that women in oppressive situations have no agency at all, we cast them invariably as victims. They are not. Women are strong.

I hope all my characters are equally real, though. This isn’t a feminist polemic. I want real people, in a real world. That was my driving aim.

Speaking of societal changes, it seemed to me that for the longest time, fantasy stories dealt far more with a maintenance of the status quo or a return to a past than with change and looking ahead to the future. Kingdoms, for instance, are always being restored; nobody ever raises a hand and wonders aloud about maybe just not having kings. There seems to be a shift recently toward a more change-focused plot. Certainly The Iron Ship gives us a society that is changing in some traditional fantasy ways (bad creatures held back in a sealed off area are coming), but also in ways that fantasy has often shied away from. Technology hasn’t been replaced or stifled by magic; it marches forward side by side (or possibly eclipsing it). And it isn’t just technology; all sorts of issues are roiling this society — environmental issues, class issues, working conditions, and so forth. Was this just the story you wanted to tell or do you see yourself in any fashion writing against a tradition in fantasy?

You can’t have a fantasy without an external threat! That tradition I am keeping. But yeah, I suppose I am consciously writing against that. I didn’t set out to write some sort of haughty “anti-fantasy” — I want this book to be an entertaining adventure, it is first and foremost a fantasy. But you write what you want to read, and I like books like this.

Fantasy is traditionally a backward looking genre. It often deals in simplicity and comfort, it has the fairy-tale logic of potboy to king. I read an article ages ago that suggested fantasy looks back to a simplified, halcyon era that preceded it, a time when the world was more “understandable.” Victorian fantasy was all virtuous Arthurian knights. Modern steampunk — which is fantasy, not SF — hearkens back to an era of machines that you could take to pieces and fix yourself.

Of course, never generalise on the internet! Fantasy has tons of worlds and books that do not do this, or don’t fit. But in a very real sense, The Iron Ship is my reaction against “traditional fantasy,” specifically I think, American High Fantasy.

Let’s talk about pacing. I said in my review that The Iron Ship is slow paced, has a “slow burn” to it in a good way, and that it rewards a patient reader in the way it takes its time to build up character. In many ways, despite its sprawling nature and all that happens within its pages, it felt almost like a prologue to the main events. Would you take issues with that characterization?

No, and yes. Is life a prologue to the main event of dying (I say pompously!)? The story is more about the characters’ lives than the threat hanging over the world — which 99% of them are entirely ignorant of. So yes and no.

Did you have any concerns about pace at all?

Maybe, I got into the characters, and became absorbed by them. I will admit that one of my big issues with fantasies that feature a ship voyage is that usually the ship doesn’t launch until page 499 of 500. I really did mean to avoid this. I singularly failed.

…or about withholding big moments or “action” scenes until near the very end?

It wasn’t my intention. But as you say, a lot does happen in this book. There’s an animated iron statue on page 10! Necromancy right after! A thousand elephants! Maybe it just feels like a prologue because the main threat doesn’t kick off. Maybe the main threat is a huge red herring. Maybe I’m making that last bit up to cover myself.

Can you give us a sense of how far into the story entire we are at this point — how many books do you envision this turning into?

It was planned as three. Book two has a lot happening in it, half of which was supposed to be in book one, so if I can I would ideally like the cycle to be four of five. But that’s a commercial as much as a creative consideration — will people stick with it for five? Who knows. I reckon if I really let myself go, it could be seven, or more. But let’s say three. Three is what it is supposed to be.

Finally, I’d like to close with two general questions. The first is one I always end my interviews with. Can you recall for us one or two of those magical moments of response to a particular scene in a book or two — those sort of “shiver moments” that make one fall in love with the magic of reading all over again or that we carry with us for years afterward.

Tough, tough, tough. There are a lot of moments like that in THE LORD OF THE RINGS. I recently experienced it (well, about seven years ago) reading part of The Dragons of Babel by Michael Swanwick, when it was published as a short story, where a boy kills a metal dragon fighter jet with elf shot. That blew me away. Robert Silverberg gets me, so does Le Guin, and Ray Bradbury fills me up with melancholy and wrings it out all over the floor.

And secondly is something we just started asking our authors for: a cocktail or food recipe, either related to something you’ve written (say, something the Countess might drink or eat), or related to your writing process (“I always find I work better after one or two…”), or just a favorite.

Ha! The countess would drink anything, and drink you under the table drinking it! I don’t drink cocktails, too sweet. Modern life’s crammed with sugar. I prefer whisky and good British ales, which I sometimes drink while writing. But only rarely, and only when I’m writing at night, else I’d be pissed (in the British sense of the word) the whole time.

Thank you for spending time with me. Readers, comment below for a chance to win a copy of The Iron Ship. I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

Everyone has been talking about this and how great it is i hope i get the copy!

Sounds like a great book! Would love to read and review!

Looks intriguing – as an aspiring fantasy author and avid reader, I would love to have a copy to treasure, read and review! :-)

This one was already on my radar but Bill’s review (and this interview) has helped it become more attractive, which means it will move up the list.

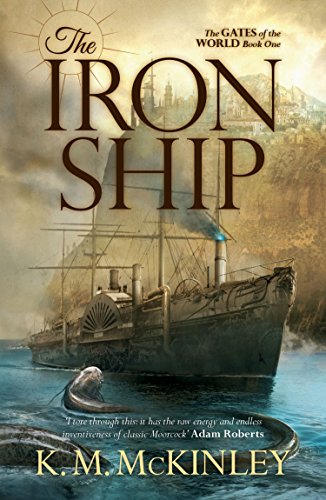

Been hearing a lot of good things about this. And I really like the cover!

That cover drew me in – as soon as I saw it I had to know more about the book. It’s been on my wish list since I first saw it. :D

This was already on my To-Read list, but this interview has really ramped up my interest.

Hadn’t heard about it before this interview. Sounds like a great book and I love the cover as well.

I’d heard about this book, but this has made me want to read it. I’ll be picking up a copy if I don’t win one. Thanks for taking the time to do the interview.

I just finished “The Iron Ship” and am ecstatic about the experience. It was incredible, it was magical, with wonderful (and wonder full) plotting, character development, writing style, and world-building — and this world-building in particular was equal to any I’ve seen in the first book of a fantasy (or science fiction) series. I loved “The Iron Ship.” The slow burn alluded to was like exquisite foreplay to the novel’s fulfilling climax. I hope Ms. McKinley can find a way to turn “The Gates of the World” into more than a trilogy, since this felt like a world I would like to spend a very long time in, and its epic scale — both that shown and that hinted at — seems like it can and should be given a lot of breathing room for more breathtaking storytelling. Superb work Ms. McKinley! Take a long bow…

On my radar!

And I love the cover.

Cat, if you live in the USA, you win a copy of The Iron Ship!

Please contact me (Marion) with your US address and I’ll have the book sent right away. Happy reading!

hi, is it possible to contact K.M. McKinley? is there a blog or website or something?

As someone who’s enjoyed this book and the two succeeding novels, I was wondering if you might do a follow up to this interview sometime and see if the author plans for a book four?