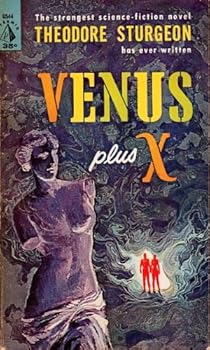

![]() Venus Plus X by Theodore Sturgeon

Venus Plus X by Theodore Sturgeon

Charlie Johns has woken up in a strange place called Ledom (that’s “model” spelled backwards) in what appears to be a future where human beings have evolved. These future humans have some really amazing technology, there’s no night, they don’t require sleep, they’ve cured many diseases, and there’s no pollution, poverty, or war.

But what’s most significant is that they’ve abolished gender — humans are now hermaphrodites. Charlie sees men who are pregnant, taking care of babies, and wearing pink bikini underwear. As he lives among these people who have no differentiated gender roles, he considers where he came from and realizes how the little biological detail of sex has had such a powerful affect on human history, society and culture.

If one purpose of science fiction is to speculate about possible futures by anticipating how advances in technology and culture might affect the human experience, you’d have to say that Theodore Sturgeon succeeds with Venus Plus X. And if another purpose of science fiction is to use future possibilities to shed light on the current condition of the human race, Sturgeon succeeds here, too. For while Venus Plus X speculates about what it would be like to live in a genderless society, it’s main purpose is to show us just how much trouble gender and sex have inflicted on us since the very beginning.

Keep in mind that Venus Plus X was published in 1960, so Sturgeon was far ahead of his time when he used a science fiction novel to contemplate sexism, the human obsession with dichotomies, and the American obsession with sex and guilt. Unfortunately, much of this feels like a lecture, especially when Sturgeon hypothesizes about how women became the “inferior” sex (perhaps men selectively bred them for physical weakness, or perhaps men trample women so they have someone to feel superior to, etc.) and what should be the proper understanding of the New Testament teaching on love.

Interspersed with Charlie’s story are little vignettes of 1950’s suburban America that point out many of our particular neuroses about sex and gender. In one of these, for example, a little boy is jealous because his father kisses and tickles his sister when he tucks her into bed but merely shakes the boy’s hand before saying good night. In another vignette, two men are discussing how otherwise sensible women have “blackout” words which make them suddenly get stupid — words such as “differential,” “transmission” and “frequency.” (Yes, I bristled at this.) Other vignettes show us how sex is associated with guilt and sin. Some show us how gender roles are already starting to blur.

Venus Plus X is definitely a novel of ideas, which is both its strength and weakness. I love Sturgeon’s ideas here (considering that this book was published in 1960), but I wish there had been more to the plot. The story takes a back seat to Sturgeon’s radical thoughts and lectures, especially in the first two-thirds of the book. Finally the plot thickens and there’s a twist at the end that had me eagerly rethinking the whole thing. I don’t think Venus Plus X is going to convince anyone that they want to live in a genderless society, and I’m pretty sure that it doesn’t intend to.

David Pringle has included Venus Plus X in his guide Science Fiction: The 100 Best Novels. I don’t know that I agree with him, but that’s simply because I wanted more entertainment. I can’t deny that the book is a classic that dealt with an important sensitive issue well before it was popular to do so (and nine years before LeGuin’s famous genderless The Left Hand of Darkness). I think it’s also telling that Venus Plus X made me think of a couple of my favorite science fiction novels — Slaughterhouse Five and A Canticle for Leibowitz. It’s also a bit reminiscent of several novels by Philip K. Dick. I listened to Blackstone Audio’s version read by one of my favorite narrators, Stefan Rudnicki.

I always got a lot out of a Sturgeon book, but I always found them to be a bit plot-light, so this doesn’t surprise me. I met him a couple of times; to me, he was an ideal of what the 1960s was supposed to be (and often wasn’t); tolerant, open to learning, questioning and smart. (And yes, I know his personal relationships were messy.)

Yeah, the ideas trump the plot, for sure.

About his messy relationships: Last night I was reading Robert Silverberg’s introduction to one of his story collections and he was talking about how in the 1950s and 60s, the SF community consisted of about 50 men who all knew each other and kept swapping spouses (as in getting divorced, annulments, remarrying someone else’s wife, etc.). I think today we’d think that was really strange.

Sounds like this could be a fascinating read. I’m interesting in looking into more gender issues in SFF fiction, and in no small part I now want to read this to look at the past looking at the possible future. Thanks for the review and for piquing my interest.

Thanks for the warning/recommendation. I can only tolerate the whole plotless-tour-through-an-idea thing very occasionally. Did you ever read William Morris’ News from Nowhere? Same problem.

It sounds like you and I read the same book! Neat ideas, particularly for the time, but it’s mostly screed rather than story. I don’t regret the time spent, but I feel I learned more about Sturgeon than gender relations in 1960.

I reviewed the book here: http://galacticjourney.org/?p=939

I like your blog, Galactic Journey!

Thank you, Kat! I hope you keep coming around!

I’ve also flagged this book as TBR because of its daring theme (at the time) and its selection for David Pringle’s 100 Best SF Novels, but I suspected it might be fairly dated and lecture-heavy, which your review confirmed for me. I suspect Left Hand of Darkness remains the most interesting exploration of gender in SF, although I’d like to read Joanna Russ’ The Female Man (1975) sometime.