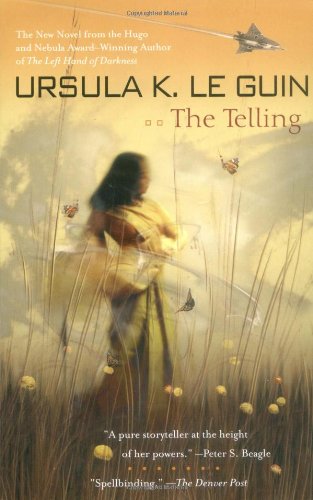

![]() The Telling by Ursula K. Le Guin

The Telling by Ursula K. Le Guin

Ursula K. Le Guinis an iconic voice whose books, like Left Hand of Darkness and The Word for World is Forest, made people rethink their assumptions of the society they lived in. She is intimidatingly intellectual but writes characters who are real and full of heart. She is a personal role model of mine, so it’s difficult to write a less-than-glowing review about The Telling, a late entry into Le Guin’s HAINISH CYCLE stories.

This slim novel is more of a philosophical study of the nature of fundamentalism than a complete story. Sutty is an Indo-Canadian language scholar who comes to the planet Aka to study its languages and literature. Space travel takes decades in planetary time; by the time Sutty arrives, sixty years after she left, she discovers a planet that has experienced a cultural revolution. Enamored of Terran high-technology, Aka has embraced a corporate, tech-loving, mechanistic belief system, and is deliberately destroying every vestige of the society’s previous culture: changing the language, replacing the traditional calligraphy with a standardized alphabet, pulping books and criminalizing traditional practices. Art and literature are sponsored and controlled by the state and have a high propaganda content; mechanical aids are plentiful but unreliable. Off-world visitors such as Sutty and her handler Tong Ov are carefully monitored and sheltered. Sutty is emotionally devastated by repeated images of books bulldozed into pits or fires, in part because they bring back the recent brush with monotheistic fundamentalist terrorism on Terra, where splinter groups have bombed libraries, colleges and schools.

To her surprise, however, Sutty is allowed to leave the large capital city and go “into the country.” Both she and Tong Ov speculate about what the reason for this might be, but Sutty still goes. In a small mountain city, Sutty discovers that the old ways are alive and thriving, and in this remote place many people still practice the Telling.

On her journey to the mountain town, Sutty encounters a government bureaucrat, a Monitor. Despite his presence, Sutty is quickly accepted by the townspeople and has no difficulty studying the hidden books and texts. Then the maz, the wise people or teachers of the Aka, invite her to the top of the mountain, where the library of Silong is housed. This may be the last library on the planet.

The middle third of this book is a lovely exploration of the nature of cultural anthropology, as Sutty learns that the old beliefs are rich, layered, convoluted and sometimes contradictory; and as she studies how to prepare food the traditional way, a way that borrows heavily from the concepts of Chinese medicine. In fact, much of the traditional culture and the new corporate overlay reminded me of China. Along the way, Sutty tries to puzzle out what caused the dramatic cultural shift fifty years earlier. She develops a theory which later the Monitor confirms for her.

This part of the book is very thoughtful, and Le Guin’s writing is beautiful as always, so it took me a while after I closed the book to realize that there is only a perfunctory attempt at a plot here, and no character growth from Sutty. She solves a mystery and brings back a powerful bargaining chip, but there is no inward growth that I can see.

Sutty’s trip up the mountain is beautiful and concretely written, and the library of Silong is original and wonderful, but the reader knows that Sutty is being followed the whole way and it seems strange that she doesn’t. The Monitor has trailed her, but her party manages to capture him before they reach the library. Now the maz have a quandary, because they cannot release him, but they do not want to hold him prisoner. Sutty engages in a series of discussions with him, explaining the recent history of Terra, pleading with the Monitor to avoid making the same mistakes Terrans did — or rather, to stop going down the road of error.

The Monitor, whose name, he tells her, is Yara, makes a devastating choice at the end of the book. His choice seems to grow less out of his internal conflict and more out of Le Guin’s need to move the story forward. The Monitor character appears as an adversary for the first third of the book, then nearly vanishes while Sutty is conveniently doing anthropology, only to conveniently reappear at the end.

Much of the book is a discussion of the nature of terrorism and fundamentalism, whether it’s religious or atheistic in nature: the Taliban dynamiting 2000-year-old statues or the Chinese Cultural Revolution destroying everything that was not Chinese, or lone lunatics in America who want to make an event out of burning other people’s sacred books. This is a powerful discussion topic but it is not new and while The Telling is sweet, Le Guin does not bring anything new to the discussion. A line from one of the maz’s stories addresses this: “Belief is the wound that knowledge heals.” Fundamentalism is evil, Le Guin tells us, but she doesn’t discuss what gives it its power, or how it can take hold so quickly.

My dilemma is that The Telling is still an interesting read and a better depiction of a foreign society than many fantasies and science fiction novels I’ve read. I just expect more from this author, so I’m rating it low because Le Guin did not write up to her full, proven potential. If you are looking for a book by this fine writer, I recommend instead some of her classic works.

~Marion Deeds

![]() I’ve got to agree with Marion on this one. As always, Le Guin’s language is beautiful, but The Telling is heavy-handed and plotless. If this had been written decades ago, it might have had more meaning, but for a book written in 2000, it’s disappointingly dull.

I’ve got to agree with Marion on this one. As always, Le Guin’s language is beautiful, but The Telling is heavy-handed and plotless. If this had been written decades ago, it might have had more meaning, but for a book written in 2000, it’s disappointingly dull.

~Kat Hooper

The Hainish Cycle — (1966-2000) From Wikipedia: The Hainish Cycle consists of a number of science fiction novels and stories by Ursula K. Le Guin. It is set in an alternate history/future history in which civilizations of human beings on a number of nearby stars, including Terra (Earth), are contacting each other for the first time and establishing diplomatic relations, setting up a confederacy under the guidance of the oldest of the human worlds, peaceful Hain. In this history, human beings did not evolve on Earth but were the result of interstellar colonies planted by Hain long ago, which was followed by a long period when interstellar travel ceased. Some of the races have new genetic traits, a result of ancient Hainish experiments in genetic engineering, including a people who can dream while awake, and a world of androgynous people who only come into active sexuality once a month, and can choose their gender. In keeping with Le Guin’s soft science fiction style, the setting is used primarily to explore anthropological and sociological ideas. The Hainish novels The Left Hand of Darkness and The Dispossessed have won literary awards, as have the novella The Word for World Is Forest and the short story The Day Before the Revolution. Le Guin herself has discounted the idea of a “Hainish Cycle”, writing on her website that “The thing is, they aren’t a cycle or a saga. They do not form a coherent history. There are some clear connections among them, yes, but also some extremely murky ones.”

It would give me very great pleasure to personally destroy every single copy of those first two J. J. Abrams…

Agree! And a perfect ending, too.

I may be embarrassing myself by repeating something I already posted here, but Thomas Pynchon has a new novel scheduled…

[…] Tales (Fantasy Literature): John Martin Leahy was born in Washington State in 1886 and, during his five-year career as…

so you're saying I should read it? :)