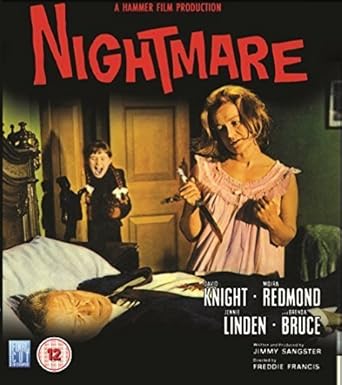

![]() Nightmare directed by Freddie Francis

Nightmare directed by Freddie Francis

1964 was a very good year for Hammer Studios in the UK. On April 19th of that year, remarkably, the studio released two films, The Evil of Frankenstein (the third entry in an ongoing series) and the psychological horror thriller called Nightmare. The following month, the little-seen entry known as The Devil-Ship Pirates was released, and on October 18th, the cinema juggernaut would do it again, by releasing two films on the very same day: The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (the second Mummy movie in that series) and a picture that would go on to become a fan favorite, The Gorgon. But it is of Nightmare that I would like to speak here, a film that this viewer had never seen before until recently, but one that has just made a hugely favorable impression on me. Clocking in at 82 very efficient minutes and impressively shot in ubercreepy B&W, the film is surely one that is ripe for rediscovery today, dishing out as it does scares and shocks, as well as a story line guaranteed to keep the viewer guessing all the way till the very end. Simply stated, I just loved this one!

1964 was a very good year for Hammer Studios in the UK. On April 19th of that year, remarkably, the studio released two films, The Evil of Frankenstein (the third entry in an ongoing series) and the psychological horror thriller called Nightmare. The following month, the little-seen entry known as The Devil-Ship Pirates was released, and on October 18th, the cinema juggernaut would do it again, by releasing two films on the very same day: The Curse of the Mummy’s Tomb (the second Mummy movie in that series) and a picture that would go on to become a fan favorite, The Gorgon. But it is of Nightmare that I would like to speak here, a film that this viewer had never seen before until recently, but one that has just made a hugely favorable impression on me. Clocking in at 82 very efficient minutes and impressively shot in ubercreepy B&W, the film is surely one that is ripe for rediscovery today, dishing out as it does scares and shocks, as well as a story line guaranteed to keep the viewer guessing all the way till the very end. Simply stated, I just loved this one!

The film introduces the viewer to pretty, 17-year-old Janet Freeman (Jennie Linden, an actress very much in the Jill Ireland mold, and a last-minute replacement for Julie Christie, supposedly; Linden would go on to appear in 1965’s Dr. Who and the Daleks and 1969’s Women In Love), who is something of a psychological wreck, having witnessed her mother killing her father with a knife when she was only 11. Poor Janet had suffered a breakdown and has had horrible dreams ever since, and when we first meet her, she is having another doozy; a nightmare in which she walks down the nighttime corridors of the lunatic asylum where her mother is currently incarcerated. Her hysterical screams upon awakening result in her getting kicked out of the Hatcher’s School for Young Ladies where she is a student, and a forced return to her ancestral home, the gloomy pile known as High Towers. Her return is at first a happy one, accompanied as she is by her favorite teacher, Miss Lewis (Brenda Bruce, whose filmography extends all the way back to 1938, and who had appeared in the great horror film Peeping Tom four years earlier), and reuniting with the mansion’s maid Mrs. Gibbs (Welsh actress Irene Richmond, who many will recall from the following year’s Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors) and chauffeur John (George A. Cooper, who had just appeared the previous year in the classic film Tom Jones). New on the scene, however, is a nurse companion named Grace Maddox (Moira Redmond, who would go on to appear that year in A Shot in the Dark), who has been provided by the lawyer who is also Janet’s guardian, Henry Baxter (handsome but weaselly David Knight, the only American actor in the cast, who would go on to do mainly TV work).

But after a nice homecoming, things rapidly deteriorate for Janet. Her dreams begin again, centered now upon a lank-haired, scar-faced woman dressed in a long, flowing white gown (and played by Australian actress Clytie Jessop, who only appeared in two other films, 1961’s The Innocents and 1967’s Torture Garden), who beckons to her and leads her through the house to her parents’ old bedroom, where she finds … the Woman In White lying on a bed, a knife sticking through her bloodied chest! The dream (or is it a dream?) is repeated on several occasions, and matters grow even worse when Janet sees the WIW appear to her in the hallway in broad daylight! After a shocking suicide attempt, Janet admits to herself that she, like her mother, is very probably on the brink of madness. And then her birthday rolls around, the anniversary of her mother’s shocking act. All Janet’s adult friends gather for a small party in her honor, and Henry Baxter even brings his wife along … a woman who Janet is appalled to find is the same scar-faced woman of her dreams! What follows is a sequence that is so jaw-dropping that most viewers will be simply flabbergasted by what they are looking at. And then … the film veers off into very strange waters indeed. That birthday party scene, you see, only occurs at the film’s halfway point, but to reveal any more would surely constitute a major spoiler of sorts, and ruin the fun for any potential viewers of this consistently twisty thrill ride.

Nightmare, indeed, is a very difficult film to write about, simply because there are so many unexpected surprises in it, and because the entire second half of the film is one that cannot be discussed without giving away so much of the fun. Take it from me, though: If you think you know where this film is going, having seen such previous exercises in fear such as George Cukor’s Gaslight (’44), William Castle’s House on Haunted Hill (’58) and, especially, Henry-Georges Clouzot’s 1955 masterpiece Diaboliques, you are wrong. This film cleaves almost perfectly evenly into two discrete sections, and each one of them is an exercise in tension and fear done to a turn, with that second section coming as a completely unexpected curveball. The film has any number of stunning scenes, and every one of Janet’s dreams, and every appearance of the WIW, is a chilling one. And oh, how I wish I could tell you of the escalating tension and surprises that are to be found in the film’s second section!

Nightmare, indeed, is a very difficult film to write about, simply because there are so many unexpected surprises in it, and because the entire second half of the film is one that cannot be discussed without giving away so much of the fun. Take it from me, though: If you think you know where this film is going, having seen such previous exercises in fear such as George Cukor’s Gaslight (’44), William Castle’s House on Haunted Hill (’58) and, especially, Henry-Georges Clouzot’s 1955 masterpiece Diaboliques, you are wrong. This film cleaves almost perfectly evenly into two discrete sections, and each one of them is an exercise in tension and fear done to a turn, with that second section coming as a completely unexpected curveball. The film has any number of stunning scenes, and every one of Janet’s dreams, and every appearance of the WIW, is a chilling one. And oh, how I wish I could tell you of the escalating tension and surprises that are to be found in the film’s second section!

Nightmare features another improbable but oh-so-clever script by Jimmy Sangster, a terrific screenwriter who was an old hand at both sci-fi and horror; his credits include X the Unknown (’56), The Curse of Frankenstein (’57), Horror of Dracula (’58), The Revenge of Frankenstein (’58), The Snorkel (’58), The Mummy (’59), The Brides of Dracula (’60), Scream of Fear (’61, and the film that really got Hammer going in the psychological horror field), The Nanny (’65), Fear in the Night (’72) and Whoever Slew Auntie Roo? (’72). His script is a marvel of economical characterization and even features some wonderful instances of acidic humor; I love, for example, when Baxter says to the, uh, reclusive nurse Maddox, “You’ve emerged, I see.” And Sangster’s script is more than abetted by the typically fine direction of Freddie Francis, another old hand at these types of affairs, whose list of horror credits, for not only Hammer but also rival British studios Amicus and Tigon, would ultimately include Paranoiac (’63), The Evil of Frankenstein, Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, The Skull (’66), Torture Garden, Dracula Has Risen From the Grave (’68), Trog (’70), Tales From the Crypt (’72) and The Creeping Flesh (’73). Francis incorporates any number of unique and interesting touches into his film, including overhead shots and off-kilter camera angles, and brings his film home while ratcheting up the tension level to a remarkable degree. Master cinematographer John Wilcox (who had also worked on The Evil of Frankenstein, The Skull and 1966’s The Psychopath) gives the B&W film a haunting feel in any number of finely shot scenes, while composer Don Banks (whose horror credits would include the 1966 Hammer classic The Reptile, 1966’s The Frozen Dead, and Torture Garden) provides some wonderfully dreary background music, especially to those nighttime dream sequences.

The film, I should also add, makes good use of absolute silence in other suspenseful scenes, to add even more tension to the affair. And finally, the film’s performers all do wonderfully convincing work here, every single last one of them, down to the smallest bit players. Jennie Linden makes for an appealing and sympathetic lead in the picture — it is a pity that her career did not go further — while David Knight and Moira Redmond, whose characters are more prominently displayed in the film’s second section, are both extraordinarily incisive and memorable. So yes, some wonderful talent both in front of and behind the cameras in this terrific horror wringer.

As much fun as Nightmare is to watch the first time, while we try to figure out just what the heck is going on, all the while sitting on the edge of our seats, a second viewing might prove just as engaging for viewers. During that repeat viewing, we can examine the characters more closely, with a knowledge of what they are really thinking as we study their facial expressions. And yes, the actors do play it fair in this regard. It is a film that I do look forward to watching for a third time somewhere down the line. The promotional poster for Nightmare, I should add, is somewhat misleading, when it proclaims “Three Shocking Murders … did she DREAM them, or DO them?” Well, yes, there are indeed three shocking murders featured in the film, but that hyperbolic blurb does not give a true impression as to what the viewer might expect here. Again, I find myself effectively stymied at revealing more. I would love to sing the film’s praises on and on, but really should not. See it for yourself, and I think you will find that the film really is something of a minor masterpiece, and yet another winner from the House of Hammer…

Way to sell the movie! Now I want to see it.

I love Hammer films.

A beautiful-looking print of the film is on YouTube for free viewing: https://youtu.be/EJizyBez6A0

Thank you!

👍