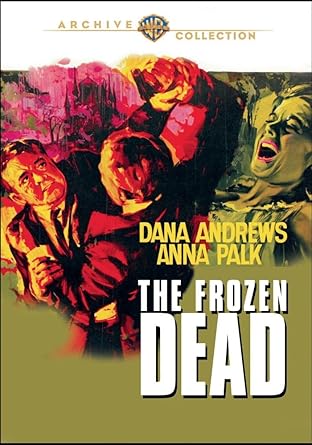

![]() The Frozen Dead directed by Herbert J. Leder

The Frozen Dead directed by Herbert J. Leder

The film career of Mississippi-born Dana Andrews seemed to undergo some kind of metamorphosis as the actor entered his third decade before the cameras. During the 1940s, the characters that Andrews brought to life were in the main sympathetic and likeable, whether they were such all-American Joes as in The Ox-Bow Incident, State Fair and The Best Years of Our Lives, or troubled cops as in Laura and Where the Sidewalk Ends. He managed to maintain that sympathetic demeanor throughout the ’50s (I particularly like him in the exceptionally fine 1957 horror film Night of the Demon), but come the 1960s, and as Andrews entered his 50s and his features coarsened a bit, his roles gradually segued into personages who were alarmingly less sympathetic.

The film career of Mississippi-born Dana Andrews seemed to undergo some kind of metamorphosis as the actor entered his third decade before the cameras. During the 1940s, the characters that Andrews brought to life were in the main sympathetic and likeable, whether they were such all-American Joes as in The Ox-Bow Incident, State Fair and The Best Years of Our Lives, or troubled cops as in Laura and Where the Sidewalk Ends. He managed to maintain that sympathetic demeanor throughout the ’50s (I particularly like him in the exceptionally fine 1957 horror film Night of the Demon), but come the 1960s, and as Andrews entered his 50s and his features coarsened a bit, his roles gradually segued into personages who were alarmingly less sympathetic.

In 1965, in the sci-fi thriller Crack in the World, his Dr. Sorenson character was so pigheaded and mistaken in his experiments that he caused the planet Earth to split in two, and that same year, in Brainstorm, he portrayed a husband so vile that the audience cheers when he is murdered in cold blood by his wife’s lover. But it was in one of his 1966 offerings, the British production The Frozen Dead, that Andrews portrayed a character with even less likeability, if possible, than any other that he had ever attempted. In this film, Dana plays the part of one Dr. Norberg, an ex-Nazi now living in England, who is working on a method of bringing back to life the dozen or so cryogenically stored soldiers of the Third Reich who have been entrusted to his care. Originally released in October of ’66 in the U.K. and over a year later in the U.S., the film is a surprisingly solid one that is immensely bolstered by Andrews’ performance in the lead role; a somewhat daring one for the formerly sympathetic Hollywood leading man.

In the film, we learn that Dr. Norbert has indeed perfected his method of bringing the Nazi corpsicles back to life but that one major problem remains: All the soldiers who have been successfully thawed out after 20 years of deep freeze are mentally unhinged; their bodies function but their minds, after having been prodded by the doctor, remain fixed on the one mania that has been hit upon. Thus, one of the soldiers can do nothing but bounce an imaginary rubber ball; another endlessly combs his hair; another thinks of himself as an old man; one sits and cowers in perpetual fear; and still another counts beads on a rosary. And then there is “Prisoner 3” (played by Edward Fox, in his first credited role), who just happens to be Norberg’s brother and the father of his niece, and who is now homicidally violent in nature.

Norberg’s travails grow even more complicated with the arrival at his country estate of Nazi general Lubeck (Czech actor Karel Stepanek) and Capt. Tirpitz (Basil Henson), who inform him that his experiments must be stepped up and his problems with the corpsicles’ minds overcome posthaste, as 1,500 more Nazi soldiers are awaiting their turn to be unthawed! Norberg declares his desire for a living human brain to study, and his wish soon attains fulfillment with the unexpected arrival of his niece Jean (Anna Palk) and her good friend Elsa (Kathleen Breck). Norberg’s weasly assistant Essen (Alan Tilvern) drugs the lovely Elsa in her sleep and later slays her, blaming the deed on Prisoner 3. Norberg decides that since the poor girl is dead anyway, he might as well use her brain as a means of study.

Thus, we soon see Elsa’s severed head in a wooden box, nourishing tubes attached to her noggin, her brain exposed but covered with some kind of transparent dome for study. And as if matters could not grow any more complex, the distraught Jean immediately starts snooping around in search of her friend; an American scientist named Dr. Roberts (a nod to the Beatles’ just released song “Doctor Robert”?), played by Philip Gilbert, arrives to help Norbert in his work; and poor Elsa begins to evince the ability to communicate telepathically with Jean and send messages into her dreams! It would seem that it is only a matter of time until Jean discovers what her uncle is up to in his basement laboratory, and that her father did NOT in fact die in a Nazi concentration camp decades before…

Those viewers who sit down to watch The Frozen Dead expecting some kind of Grade Z spectacle might be a bit surprised at what they wind up getting instead. The film, despite its outrageous premise, is very much a class production — this is decidedly not a shlock movie — and director/producer/writer Herbert J. Leder, who had previously been responsible for the script for the great sci-fi film Fiend Without a Face and who would go on to write and direct the Roddy McDowall/Jill Haworth film It!, does a fine job in all three departments here. What a double feature this film and It! must have made, when the two first appeared together here in the States in November ’67! The film looks terrific, even sumptuous in parts, and was shot in beautiful Eastmancolour, but strangely enough, when shown here in the U.S., it was screened in B&W; I am very glad that I recently got to see it in its original color, so as to better appreciate its often surprising visuals. Plus, in B&W, the audience never got to see that Elsa’s head, in that wooden box, was the strangest shade of aqua blue – a most disconcerting visual, indeed – or the bizarre tints in that wall of living arms (!) that Norbert has in his basement.

In the lead female role, Anna Palk (who had previously appeared in such horror affairs as The Earth Dies Screaming and The Skull) is both lovely and shapely, and Kathleen Breck is surprisingly effective as that living head, making the most of mere eye movements and grimacing expressions. Her final words as the film closes — “Bury me, bury me” — should linger long in the viewer’s memory. As for Andrews, he is rock solid here, playing his role absolutely straight and even — dare I say it — bringing a note of sympathy to his character. Here is a crazed Nazi scientist who balks at killing — he would never condone murder to obtain his living brain, which is why Essen feels compelled to do the dirty deed himself — and who is shocked to the core when he learns of what Essen has done. (Andrews is such a terrific actor that we can tell his reaction via his eyes alone.)

The Frozen Dead, of course, was just one of many offerings in the curious horror subgenre that might be called “Nazi zombie films.” It is assuredly superior to the legendary camp classic Madmen of Mandoras (1963), which was recast as They Saved Hitler’s Brain in 1968, and more fun than 1977’s Shock Waves. (I still have not gotten around to seeing such Nazi zombie films as 1981’s Zombie Lake, 1982’s Oasis of the Zombies and 2009’s Dead Snow.) As regards the subgenre of films that I suppose might be called “living heads,” The Frozen Dead is not nearly as deliriously crazy as The Brain That Wouldn’t Die (1962) or as startlingly bizarre as the 1959 German film simply entitled The Head, but is still capable of stunning the viewer with any number of outré segments, and indeed, the final fates of Dr. Norberg and Gen. Lubeck must be seen to be believed! I’m not sure that even 1,500 revived Nazi soldiers would have made an effective army in the nuclear era of 1966, but thank goodness that Elsa here was still capable of using her head!

I’ve never seen this but for some reason head-in-a-box Elsa is familiar. I wonder if I’ve seen that image in some horror montage somewhere, or if some Grade C movie stole the idea and I saw that.

And –picky, picky! — A Nazi with a rosary? Really?

I have a feeling that you may have seen “The Brain That Wouldn’t Die,” Marion; it’s a little more well known than this one….