![]() The Sunken World by Stanton A. Coblentz

The Sunken World by Stanton A. Coblentz

Ever since reading the truly beautiful and unforgettable fantasy When the Birds Fly South (1945) around 3 ½ years back, I have wanted to experience another book from the San Francisco-born novelist and poet Stanton A. Coblentz. Unfortunately, just as “Coblentz” is not exactly a household name these days, his books are hardly to be found at your local modern-day bookstores. Coming to my rescue once again, however, were the fine folks at Armchair Fiction, who currently have no fewer than five of the author’s titles in their very impressive catalog. Choosing at random, I opted for Coblentz’s very first piece of fiction, The Sunken World … and a very fortuitous choice it has turned out to be!

The Sunken World was Coblentz’s 4th book, actually, following two nonfiction works and a volume of poetry. It first saw the light of day in the Summer 1928 issue of Amazing Stories Quarterly, when its author was 32 years old, and was later reprinted in that same magazine’s Fall 1934 issue. In 1948, it appeared in book form as a Fantasy Publishing Co. hardcover, its contents updated to include a WW2 backdrop. Happily, the book has been reprinted a good half dozen times since then, and my 2012 edition from Armchair is not even the novel’s most recent incarnation. Thus, this relatively unknown work has yet managed to enjoy a successful publication history … and for good reason, as it turns out. Like Coblentz’s 1945 masterpiece, this is a beautifully written lost-world fantasy, but rather than being set at the top of the world, among the towering peaks of Afghanistan, this first novel transpires in the bottommost depths of the Atlantic.

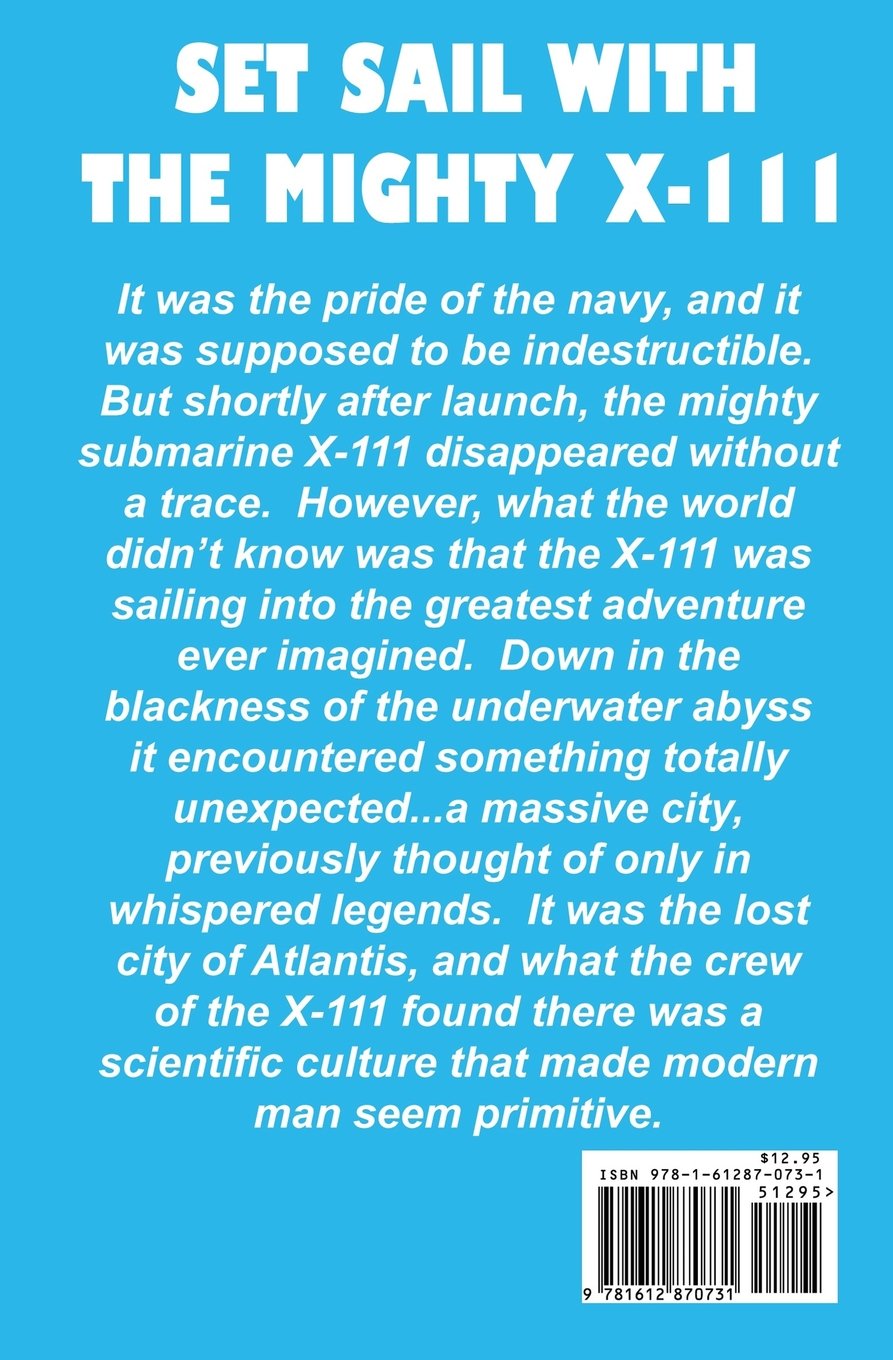

The book is narrated to us by Anson Harkness, who, along with 38 others, had been lost at sea five years earlier when their supposedly unsinkable submarine, the X-111, had gone missing. Ensign Harkness thus tells his tale of what had actually happened to that submarine and its crew five years before. It seems that, like the Titanic some years previous, the supposedly unsinkable craft had proved all-too vulnerable, after colliding with a partially submerged derelict and then engaging in inconclusive battle with a German U-boat. The X-111 had sunk steadily, well past the 4,000-foot level, and was on the brink of being crushed like a tin can, when it had sighted a fantastical city on the ocean floor. Surrounded and encased by a protective glass hemisphere, the city had seemed to feature vast temples, colonnades and statuary. But before any more could be seen, the sub had been sucked into a maelstrom of sorts, tossing the 39 men about and causing them all to lose consciousness. When they had come to, they’d realized that the X-111 had been drawn inside the dome (via a main intake valve, as is later learned). Search teams had been sent out, and when they’d failed to return, Harkness and young crewman Rawson were ordered to make a reconnaissance. And to the pair’s astonishment, it was soon learned that they had discovered the actual remnants of fabled Atlantis, whose half million or so inhabitants had happily dwelt beneath their 500-foot-high dome — a dome of 200 miles in diameter — ever since their ancestors had deliberately caused the island continent to sink 3,035 years before!

The book is narrated to us by Anson Harkness, who, along with 38 others, had been lost at sea five years earlier when their supposedly unsinkable submarine, the X-111, had gone missing. Ensign Harkness thus tells his tale of what had actually happened to that submarine and its crew five years before. It seems that, like the Titanic some years previous, the supposedly unsinkable craft had proved all-too vulnerable, after colliding with a partially submerged derelict and then engaging in inconclusive battle with a German U-boat. The X-111 had sunk steadily, well past the 4,000-foot level, and was on the brink of being crushed like a tin can, when it had sighted a fantastical city on the ocean floor. Surrounded and encased by a protective glass hemisphere, the city had seemed to feature vast temples, colonnades and statuary. But before any more could be seen, the sub had been sucked into a maelstrom of sorts, tossing the 39 men about and causing them all to lose consciousness. When they had come to, they’d realized that the X-111 had been drawn inside the dome (via a main intake valve, as is later learned). Search teams had been sent out, and when they’d failed to return, Harkness and young crewman Rawson were ordered to make a reconnaissance. And to the pair’s astonishment, it was soon learned that they had discovered the actual remnants of fabled Atlantis, whose half million or so inhabitants had happily dwelt beneath their 500-foot-high dome — a dome of 200 miles in diameter — ever since their ancestors had deliberately caused the island continent to sink 3,035 years before!

Eventually, all 39 crewmen had been gathered in the Atlantean capital city of Archeon, where they were taught to speak the language of their hosts. And so, over the course of the next five years, the men of the X-111 had been kindly treated and were allowed every freedom … except the freedom of returning to their home, the Atlanteans wishing to preserve the secret of their existence from the savage world that they had willingly renounced three millennia earlier. Of all the men, Harkness had adapted most easily, an earlier knowledge of the Greek language enabling him to quickly master the new tongue. He was made a citizen, thus, and had been given a monthlong tour of all the surrounding cities and various works. And, as had Dan Prescott in the 1945 novel, he had fallen in love with one of the local women, a beautiful blonde tutor and dancer named Aelios. (Whereas Prescott’s Yasma had been described in terms suggesting a bird, Aelios is at first compared to a butterfly.) Harkness and Aelios had eventually married and all seemed to be going well for the resigned ensign … until, that is, a leaking crack in the centuries-old dome had been detected, spelling possible disaster for the ancient civilization…

Now, of course, Coblentz’s The Sunken World hardly marked the first time that Atlantis and its inhabitants had been used as the linchpin of a fantasy tale, and indeed, the subject of the legendary continent itself can be seen as a distinct subgenre of the lost-race novel. I have already written here of such books as C. J. Cutcliffe-Hyne’s The Lost Continent (1899), which detailed the events leading up to the empire’s destruction; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Maracot Deep (1929), which was set in the present day and revealed how the remnants of Atlantis were surviving beneath the ocean floor; and S. P. Meek’s The Drums of Tapajos (1930) and its sequel Troyana (1932), which depicted the Atlanteans as barbarous slaves in a modern-day lost world in the wilds of Brazil. Patiently sitting on my bookshelf and waiting to be read is Pierre Benoit’s 1919 classic L’Atlantide (aka Queen of Atlantis), in which the lost continent’s remnants are (from what I hear) discovered in the midst of the Sahara Desert! In addition, there is a novel out there from one David M. Parry, 1906’s The Scarlet Empire, which also depicts Atlantis surviving on the ocean floor in the modern-day world and beneath a protective glass shield. So Coblentz cannot be said to have gotten to the subject first, but at least his conception of the Atlanteans deliberately and purposefully submerging their civilization — and employing some 30,000 men over a 34-year period to construct the dome before the inundating cataclysm was touched off — is a novel one.

Now, of course, Coblentz’s The Sunken World hardly marked the first time that Atlantis and its inhabitants had been used as the linchpin of a fantasy tale, and indeed, the subject of the legendary continent itself can be seen as a distinct subgenre of the lost-race novel. I have already written here of such books as C. J. Cutcliffe-Hyne’s The Lost Continent (1899), which detailed the events leading up to the empire’s destruction; Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Maracot Deep (1929), which was set in the present day and revealed how the remnants of Atlantis were surviving beneath the ocean floor; and S. P. Meek’s The Drums of Tapajos (1930) and its sequel Troyana (1932), which depicted the Atlanteans as barbarous slaves in a modern-day lost world in the wilds of Brazil. Patiently sitting on my bookshelf and waiting to be read is Pierre Benoit’s 1919 classic L’Atlantide (aka Queen of Atlantis), in which the lost continent’s remnants are (from what I hear) discovered in the midst of the Sahara Desert! In addition, there is a novel out there from one David M. Parry, 1906’s The Scarlet Empire, which also depicts Atlantis surviving on the ocean floor in the modern-day world and beneath a protective glass shield. So Coblentz cannot be said to have gotten to the subject first, but at least his conception of the Atlanteans deliberately and purposefully submerging their civilization — and employing some 30,000 men over a 34-year period to construct the dome before the inundating cataclysm was touched off — is a novel one.

Coblentz’s novel is pleasingly detailed, and his feat of underwater world building is an impressive one. Thus, the reader learns all about the various Atlantean cities, and how the people therein manage to procure their fresh water, electricity, breathable air, and foodstuffs. We become privy to the political situation in the land, and get to hear the debates between the most popular faction, the Submergence Party (which espouses the cause of Agripides, the Atlantean of 3,100 years ago who had first proposed the deliberate inundation), and the much-reviled Emergence Party, which argues in favor of living on the land once again. (The fact that Harkness befriends Xanocles, one of the heads of the Emergence Party, and later joins that party himself, does not put him in a good light with either his adopted people or with Aelios, the woman he spends most of the book trying to woo.) We also see the various Atlantean entertainments, learn about the libraries and planetarium, witness an Atlantean marriage ceremony (that between Harkness and Aelios, after he finally wins her favor), take a tour through the Archeon City Museum, and hear something of the people’s unusual religious beliefs.

Throughout, Coblentz uses the idyllic, utopian paradise that is Atlantis to point out its many superiorities over our own modern-day existence. A theatrical performance depicting the horrors that prevailed in the pre-enlightened Atlantis before the Submergence reveals a mechanical, polluted civilization that is very nearly a twin of our own. And after Harkness is told to write a history of the Upper World of the past 3,000 years, for the Atlanteans’ enlightenment, the populace is shocked by his narrative, replete as it is with violence, wars and injustice. As Xanocles puts it:

“…It grieves me deeply to hear of the deplorable state of the Upper World. No doubt our friend has unconsciously exaggerated, for it is incredible that, after all these thousands of years, the unsubmerged races should still be in a primitive stage. Yet we must accept the picture as he paints it; we must reluctantly admit that our earth fellows are groping in the semi-savagery of the Age of Smoke and Iron, from which we Atlanteans escaped three thousand years ago…”

And when Aelios hears of the American custom of charging money for theatrical entertainments, she is shocked to her core, declaring:

“…Fancy being charged for beauty or ecstasy or dreams… Why, you would as soon think of paying for the air you breathe, or the light that shines upon you. The State recognizes the theatre as the birthright of every citizen, just as it recognizes poetry, music and education. We all take part in giving the performances, and everyone is invited…”

So yes, Coblentz’s first novel, besides telling a wonderfully imaginative story, also has some real points to make, and the lesson is not an easy one to hear. While perusing The Sunken World, the reader will inevitably be impressed by the fact that this was its author’s very first go at a fictional piece, even taking into consideration the updated bits that the more seasoned Coblentz added in some two decades later. It is a hugely successful novel, its prose evincing its poet author’s love affair with the English language, and it is ultimately a very moving one. Alternating as it does scenes of travelogue, romance and historical exposition, and culminating with a nail-biting race against time and tragedy, the book is well-nigh unputdownable; at least, this reader found it to be so. Coblentz very obviously felt the subject of Atlantis to be a compelling one (indeed, in 1960 he would come out with a volume entitled Atlantis and Other Poems), and his enthusiasm is really quite contagious. In his introduction, he remarks, regarding Harkness’ narrative, that “his pages should prove of interest,” in an instance of classic understatement. To be more accurate, Ensign Harkness’ pages comprise a truly fascinating book.

As for me, up next will be another novel from Stanton A. Coblentz, also available from the catalog of Armchair Fiction: 1931’s Into Plutonian Depths. And this one looks to be still another Radium Age doozy! Stay tuned…

Trackbacks/Pingbacks