![]() When the Birds Fly South by Stanton A. Coblentz

When the Birds Fly South by Stanton A. Coblentz

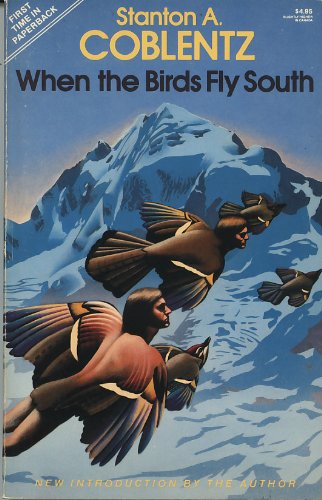

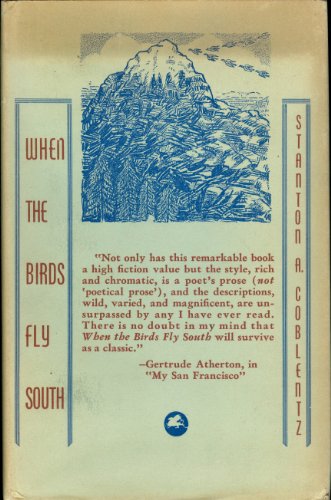

Never let it be said that you can’t learn anything from Facebook! It was on the Vintage Paperback and Pulp Forum there, for example, that this reader recently discovered his newest favorite author. Several of my very knowledgeable fellow members on that page happened to be discussing the merits of a writer who I had previously never even heard of before; a man with the curious name Stanton A. Coblentz. Very much intrigued, I later did a little nosing about, and managed to lay my hands on Coblentz’ highly regarded When the Birds Fly South. And I am so glad that I did. This novel, as the author revealed later, was his very favorite of all his many sci-fi/fantasy works. It was, appropriately enough, originally released in 1945 as a Wings Press hardcover (“wings,” birds, and flight are central images in the book’s story line), and afterward languished in relative obscurity, until the editors of the esteemed Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy Classic series revived it in 1980, and with a pleasing introduction by its author. Thus, after 35 years of neglect, Coblentz’ name, as well as his favorite creation, were made accessible to a new generation of readers. It was the Newcastle edition that this reader was fortunate enough to acquire, although the novel has been republished twice since then.

Very much a lost-race fantasy of the type popularized some 60 years earlier by the great H. Rider Haggard, When the Birds Fly South is narrated, at some remove in time, by its main protagonist, Dan Prescott. Prescott had been a 33-year-old geologist, exploring the summer valleys of Afghanistan with a team of nine other scientists and their native guides, when a very unusual mountain had been discovered. At its top stood what appeared to be an enormous statue of a woman, with her arms uplifted as if in prayer. Prescott and one of his colleagues had attempted to climb to the summit and look over this unexpected wonder, but a sudden fog had separated the two men, and caused Dan to tumble down a slope and break his right arm. Fortunately, he was later rescued by a curious group of people known as the Ibandru, who had taken Dan to their hidden valley, cupped in the mountainous solitudes. There, Dan healed after some time, and soon fell in love with the charming, 17-year-old woman, Yasma, who had nursed him back to health.

But come November, when the birds flew south, the entire tribe had disappeared, one by one, leaving Prescott to fend for himself for the entire winter. And come spring, the Ibandru had just as mysteriously reappeared. Before long, Dan had pressured Yasma into marriage, even though the young maiden protested that Yulada (the above-mentioned statue, which the Ibandru worshipped as a goddess) would never permit it, and that come the following winter, she must once again migrate south without him. But despite the dire warnings of the tribal soothsayer Hamul-Kammesh, the marriage had proceeded. And all had indeed gone well, even after Yasma had mysteriously vanished and left Dan alone again for a second winter. But when Prescott had physically restrained her from leaving during his third winter in the valley of Sobul, that is when tragedy had descended on them all…

Despite having been chosen by the Newcastle people as the 23rd in their well-regarded series of 24 forgotten fantasy gems, When the Birds Fly South only barely squeaks by as a fantasy work, I feel. In the main, it is almost a tale of romance with an admixture of lost-race anthropology. Although the cover of the Newcastle edition depicts (in spoilerish fashion) the pleasing fantasy image of winged humans soaring over mountains alongside their avian companions, the novel itself is far more subtle. And indeed, those readers who are hoping for a scene in which Prescott sees Yasma and the other Ibandru sprout wings and take off might be a tad disappointed at how things play out here. Likewise, it is left ambiguous by the author whether or not Yulada has any godlike abilities or not. Thus, what we are left with is more of an understated, restrained, low-key fantasy, in which things are suggested and implied, rather than blatantly spelled out. But oh my goodness, what a beautiful fantasy it is!

Stanton Coblentz, besides being a writer of pulp sci-fi, was also an accomplished poet, as any reader who ventures a few chapters deep into this, his favorite novel, will most likely begin to suspect fairly quickly. To be succinct, his book is beautifully, almost lyrically written. It is as if one of Haggard’s classic lost-race novels were being done over by an author with the soul of a genuine poet, although nobody has ever topped Haggard at this type of tale. Coblentz writes simply but effectively, and his love scenes and descriptions of nature are to be marveled at. Thus, when the snowbound Prescott awakens one morning after a fierce blizzard, we get this:

It was an altered world that greeted me; the clouds had rolled away, and the sky, barely tinged with the last fading pink and buff of dawn, was of a pale, unruffled blue. But a white sheet covered the ground, and mantled the roofs of the log huts, and wove fantastic patterns over the limbs of leafless bushes and trees. All things seemed new-made and beautiful, yet all were wintry and forlorn — and what a majestic sight were the encircling peaks! Their craggy shoulders, yesterday bare and gray and dotted with only an occasional patch of white, were clothed in immaculate snowy garments, reaching far heavenward from the upper belts of the pines, whose dark green seemed powdered with an indistinguishable spray…

The entirety of When the Birds Fly South is like this, written in a style that is almost like prose poetry and that effortlessly pulls the reader in. Coblentz’ story is a fascinating, highly atmospheric one; the Ibandru natives who we get to know (mainly Yasma’s father and two brothers) are admirable and intelligent men; and Yasma herself — elfin child of nature that she is — is both lovable and sympathetic. She and Prescott are both well-drawn, appealing characters, although, if Dan has our full sympathies as his narrative begins, we do start to lose some of that sympathy for him as his stubbornness and blindness begin to precipitate tragedy. And this lost fantasy really is a sweet, tender and tragic romance, well deserving of a modern-day reappraisal. I couldn’t wait to get home from work to sit down and get back into it — a sure sign of a gripping novel, well told — and the evenings that I spent getting deeper and deeper into Coblentz’ hidden valley of Sobul were very pleasant ones for me, indeed.

Actually, I quite loved this book, and Coblentz’ beautiful writing style. When the Birds Fly South is a memorable, unique novel that I unreservedly commend to all readers’ attention. I find myself wanting to familiarize myself with more of Stanton A. Coblentz; his wonderfully titled novels After 12,000 Years (1950), Into Plutonian Depths (1950), Under the Triple Suns (1955) and The Crimson Capsule (1967) even now seem to be exerting their siren song on me. Stay tuned…

![]() I am indebted to Sandy for reviewing this book, for I would certainly not have heard of it without him. Lured by the promise of something rescued from oblivion I tracked down the version published by Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy. As Sandy says, the language is beautiful, and this is a story that demands re-reading for anyone with a penchant for a lovely sentence.

I am indebted to Sandy for reviewing this book, for I would certainly not have heard of it without him. Lured by the promise of something rescued from oblivion I tracked down the version published by Newcastle Forgotten Fantasy. As Sandy says, the language is beautiful, and this is a story that demands re-reading for anyone with a penchant for a lovely sentence.

In fantasy-terms, When the Birds Fly South is very subtle. For the most part, the Ibandru (the lost tribe discovered by the story’s protagonist, Prescott), are perfectly human. There is no “big reveal”. Instead there are constant hints as to the Ibandru’s nature throughout. The idea that their true form is dictated by a powerful, natural force that cannot be cheated or resisted is powerfully communicated.

It is Yasma, the young woman who Prescott falls for who makes this so plain. As she says:

Could I make my heart stop beating for you? Could I cease breathing and still live because you wish it of me? No, no, no, do not ask me to change my nature!

Through her anguish she perfectly encapsulates the inextricable tie between the Ibandru and the birds that must fly south each Winter, a tie that cannot and must not be broken, not even for love.

I was torn throughout by compassion for Prescott, who is so blinded by his love for Yasma that he cannot let her go, and frustration when he tries to restrain her. At times this frustration did get the better of my enjoyment of the story and I found myself wishing I could shake him and send him home. For the most part, though, I appreciated the creeping tension that comes from Prescott’s internal conflict.

In some ways When the Birds Fly South is a product of its time (I’m thinking of the liberal use of exclamation marks in particular), but that’s certainly not a barrier to enjoyment. When the Birds Fly South is a profoundly moving story that stands the test of time.

~Katie Burton

The excerpt you provided really is lovely! If I happen to see a copy of this anywhere, I’ll definitely give it a chance based on your review.

I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying this beautifully well-done book. Hope you DO run across it one day, Jana….

It certainly has an element of old fairy tales, with the human man trying to compel a supernatural female (by stealing her feathered cloak, etc) and ruining everything as a result.

The language is beautiful and I do hear echoes of some of Haggard’s work in the plot summary.

Oh, it’s a beautiful book, Marion! I think you would surely enjoy it. And BTW…if you think you detect signs of Haggard here, wait till you read my review for Jack Williamson’s 1933 classic “Golden Blood” (coming your way soon), which has SO many “homages” to “She”….

SO glad that you enjoyed this one as much as I did, Katie! Great minds think alike!

Indeed they do! This is definitely one to keep on the bookshelf in pride of place.

Great reviews by both of you, love the cover work and the story sounds enchanting. Can I just have another lifetime to read all these books!