![]() White Zombie directed by Victor Halperin

White Zombie directed by Victor Halperin

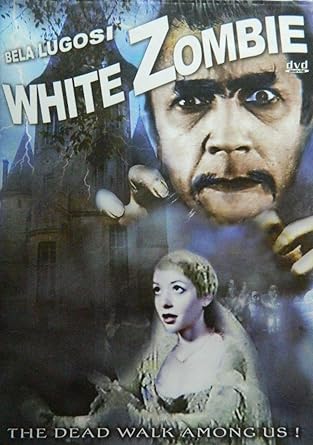

As I mentioned in my recent review of the 1936 nonthriller Revolt of the Zombies, this film was a belated follow-up of sorts (it is hardly a sequel, as many claim) to 1932’s White Zombie, the original zombie picture, but whereas that original had been an artfully constructed wonder, the latter film was something of a labor to sit through; a movie about the revivified living dead featuring terrible editing, laughable thesping, risible special effects and, worst of all, not a single scary moment to be had. The contrast between the two films, despite the fact that both were products of the Halperin brothers (Arkansas-born director Victor and producer Edward), is a striking one; a contrast that was only strengthened for this viewer yesterday, after watching the 1932 film once again. Released in July of that year, White Zombie showcases the talents of the great Bela Lugosi in one of his finest performances. Lugosi, after years of bit parts on stage at the National Theatre of Hungary, was surely on a roll at this point in his career; in February ’31, Dracula had been released to great popular and critical acclaim, and in February ’32, Murders in the Rue Morgue had solidified his position as one of the preeminent horror actors of his day. And so, what more appropriate role for Lugosi to essay next, other than the one he had here, as Murder Legendre, the zombie master of a Haitian sugar mill? But I am getting ahead of myself.

As I mentioned in my recent review of the 1936 nonthriller Revolt of the Zombies, this film was a belated follow-up of sorts (it is hardly a sequel, as many claim) to 1932’s White Zombie, the original zombie picture, but whereas that original had been an artfully constructed wonder, the latter film was something of a labor to sit through; a movie about the revivified living dead featuring terrible editing, laughable thesping, risible special effects and, worst of all, not a single scary moment to be had. The contrast between the two films, despite the fact that both were products of the Halperin brothers (Arkansas-born director Victor and producer Edward), is a striking one; a contrast that was only strengthened for this viewer yesterday, after watching the 1932 film once again. Released in July of that year, White Zombie showcases the talents of the great Bela Lugosi in one of his finest performances. Lugosi, after years of bit parts on stage at the National Theatre of Hungary, was surely on a roll at this point in his career; in February ’31, Dracula had been released to great popular and critical acclaim, and in February ’32, Murders in the Rue Morgue had solidified his position as one of the preeminent horror actors of his day. And so, what more appropriate role for Lugosi to essay next, other than the one he had here, as Murder Legendre, the zombie master of a Haitian sugar mill? But I am getting ahead of myself.

White Zombie opens most effectively indeed, as we encounter pretty Madeleine Short (Madge Bellamy, who had previously appeared in roughly 50 silent films) and her fiancé, Neil Parker (John Harron), being driven by coach through the nighttime countryside of Haiti. After stopping to witness a funeral taking place in the middle of the road (corpses, it seems, are buried under the main thoroughfare so as to prevent grave robbing!), the two encounter Legendre himself, accompanied by a passel of his walking-dead sugar mill workers. Their coach driver bolts in fright and brings them to their destination, the palatial home of plantation owner Charles Beaumont (Robert W. Frazer), who had met Madeleine on board a ship during her sea voyage to the island, and had immediately fallen in love with her. Distraught at the prospect of Madeleine being engaged to another man, Beaumont pays a visit to Legendre’s sugar mill and asks him for assistance. Murder is more than willing to oblige, giving the lovesick wretch a potion of sorts to put into the bride’s marriage bouquet.

And so, after the ceremony is complete and the marriage feast begins, Madeleine falls into a swoon and then appears to cease breathing. She is entombed in an underground crypt, and later brought back to life at the castle home of Legendre. She is now a blank-eyed zombie who can only tinkle on the piano with vacant eyes, while Beaumont thinks twice about his decision to have a rather soulless girlfriend, and Parker drinks himself into depressed oblivion … until, that is, a visit to Madeleine’s crypt reveals her body to be missing. It is only then that the sodden fiancé rallies, seeks the assistance of kindly local missionary Dr. Bruner (Joseph Cawthorn; I might add here that Cawthorn and Lugosi are pretty much the only cast members here whose careers did not peter out after the advent of the talkies), and goes to rescue his zombie bride….

By all reports, White Zombie was shot in a mere 11 days and at a cost of only $50,000, although the viewer would never know it. This is a beautifully shot, artfully produced film that looks simply sensational. Stealing the show for this viewer are the wonderful lensing of cinematographer Arthur Martinelli (whose work on Revolt of the Zombies was not nearly as impressive, but who would continue to work prodigiously all the way to the end of the 1940s) and the sets that were borrowed from Dracula, 1923’s The Hunchback of Notre Dame and 1931’s Frankenstein. The interior of Legendre’s castle is truly spectacular to look at, and the exterior, shown as a most impressive painted backdrop against a gloomy seascape, is quite convincing. And thanks to Martinelli’s great contribution here, the viewer can freeze just about any moment from this film and marvel at what is in essence a work of B&W art.

Garnett Weston’s script for the film is concise and streamlined (the entire film runs to a mere 73 minutes), and Halperin’s direction really is quite impressive. He manages to almost bring a sense of Germanic Expressionism to certain scenes, such as the one in which Neil is drinking himself into a stupor in a Haitian nightclub, with the shadows of dancers swirling behind him and Madeleine’s ghostly image appearing before him. Halperin makes very fine use of his nighttime shooting, of shadows, of scrawny trees, of the eerie Haitian chants, of split screens and impressive “wipe” editing, and, most memorably, of close-up shots. Indeed, the image that most will recall from this film is that of Bela’s eyes in concentrated close-up (not until 1946’s The Spiral Staircase, perhaps, would another film make such impressive use of an extreme close-up of a man’s concentrated orbs), and of his interlocked fingers as he wills others to do his bidding. (Madeleine’s eyes, it might be added, are almost as huge, bulging and glaucomic as Murder’s. And personalitywise, the woman is a bit of a zombie herself, it seems to me, even before she arrives in Haiti! What ever does Neil see in her?)

Garnett Weston’s script for the film is concise and streamlined (the entire film runs to a mere 73 minutes), and Halperin’s direction really is quite impressive. He manages to almost bring a sense of Germanic Expressionism to certain scenes, such as the one in which Neil is drinking himself into a stupor in a Haitian nightclub, with the shadows of dancers swirling behind him and Madeleine’s ghostly image appearing before him. Halperin makes very fine use of his nighttime shooting, of shadows, of scrawny trees, of the eerie Haitian chants, of split screens and impressive “wipe” editing, and, most memorably, of close-up shots. Indeed, the image that most will recall from this film is that of Bela’s eyes in concentrated close-up (not until 1946’s The Spiral Staircase, perhaps, would another film make such impressive use of an extreme close-up of a man’s concentrated orbs), and of his interlocked fingers as he wills others to do his bidding. (Madeleine’s eyes, it might be added, are almost as huge, bulging and glaucomic as Murder’s. And personalitywise, the woman is a bit of a zombie herself, it seems to me, even before she arrives in Haiti! What ever does Neil see in her?)

The film is loaded with all sorts of neat little touches (I love seeing steam issuing out of Bela’s mouth in that sugar mill scene, even though this film IS supposedly set in the tropics), and features any number of exciting sequences. My favorites: that first look inside Murder’s sugar mill, as the blank-eyed zombies endlessly rotate around a grinding wheel, one even falling nonchalantly to his doom beneath the grinder; Neil’s entering that underground crypt from which Madeleine’s body has been abducted, as the viewer waits from outside for his inevitable scream of horror; and that final culminating scene, with Murder and his zombies encountering Neil high atop his castle, on an outdoor terrace above the crashing sea. Others have rightfully commented regarding the fairy talelike nature of this film – of how Madeleine almost comes off as the princess being poisoned and put to sleep, after which her good prince must come to the evil castle to rescue her – and I suppose that these folks surely are correct in pointing this out. For this viewer, however, the entire film is like one extended tropical fever dream, surrealistic in spots, nightmarish in others. However one chooses to look at it, however, it really is some impressive piece of work from Halperin & Co.

“But wait,” I can almost hear you asking. “How about those zombies, and how about Bela himself?” Well, the good news is that those zombies are suitably chilling in this, the very first zombie outing. Old men, for the most part, who were Murder’s former enemies, these walking-dead wretches are appropriately horrible looking and truly creepy, their shambling gait the prototype exemplar for all future zombies to come. And Bela here is simply marvelous! While the rest of the cast overacts shamelessly (charmingly, perhaps, but still), in that overdone manner of the silents, Lugosi here offers up one of the finest, nonhammy, noncampy performances of his career. How wonderful he is, when Neil first encounters him and asks of his zombies “Who are they?,” and Legendre replies “For you, my friend, they are the angels of death!” Legendre is a terrific character, an imposing one as well, his makeup job here being another creation from the great Jack Pierce, who had done wonders on Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein Monster the previous year. Bela would go on to have a very respectable 1932, appearing in such films as Chandu the Magician and Island of Lost Souls later that same year, but his Legendre character here is perhaps one of his most memorable.

So yes, creaky and prehistoric as the film is, as overacted as it is for the most part, and as brief as its running time may be, White Zombie still delivers the requisite goods for the modern-day horror buff. Unlike some other zombie films that would come in later years, this one does manage to give the viewer a residual chill. It is infinitely superior to the 1936 film – which, dull and slow moving as it is, really has nothing to commend itself to modern-day attention – although perhaps not quite as literate and artfully done as Val Lewton’s remarkable 1943 film I Walked With a Zombie. (And incidentally, the 1941 zombie comedy King of the Zombies, featuring the absolutely hilarious Manton Moreland, is entertaining in the extreme, while the 1966 Hammer film The Plague of the Zombies, which sets its working zombies in a Cornish tin mine in 1860, is also very well done.)

Zombie films would of course undergo a sea change after George A. Romero’s astonishing Night of the Living Dead in 1968, which transformed those living dead into bloodthirsty gut munchers instead of laboring automatons, but there is a certain morbid charm and authenticity (if that’s the right word) to those earlier films that for this viewer remain quite irresistible. Today, of course, the zombie movie constitutes an entire film genre unto itself, and thus, it is nice to occasionally go back and take a look at where the whole zombified ball got rolling. And for this genre, that film is White Zombie, a film that was not well received critically back in the day, although it was popular with audiences. Still, it is a picture that remains a very solid entertainment, at this writing over 88 years since its debut. More than highly recommended!

I was reading along with no trouble suspending disbelief until I got to "internet influencers!" And then I thought, "Well,…

I recently stumbled upon the topic of hard science fiction novels, by reading a comment somewhere referring to Greg Egan's…

This story, possibly altered who I would become and showed me that my imagination wasn't a burden. I think i…

I have been bombarded by ads for this lately, just in the last week. Now I feel like I've seen…

Hi Grace, I'm the director of the behavioral neuroscience program at the University of North Florida, so I teach and…