Kincar’s grandfather, the warlord of their Gorthian clan, is on his deathbed. Kincar assumes that he and his half-brother will soon be forced to contend for leadership of the clan but, before he dies, his grandfather informs Kincar that Kincar’s father was a Star Lord, one of the mighty (human) race who can travel to other worlds. Encouraged by his grandfather, accompanied by his trusty animal companion (a bird of prey), and armed with a handy magical amulet, Kincar leaves his Gorthian family to join his father’s people.

When he meets the Star Lords, they explain that they have had too much influence on Gorth, causing it to develop faster than it naturally would have. They will now use a gate to travel to a parallel Gorth which they hope will be uninhabited by humanoid species.

But things go awry and they end up in an alternate Gorth where, Kincar is surprised to discover, people are afraid of them. In this universe, the Star Lords have used their secret knowledge and technologies to rule that world brutally. In fact, one of these brutal warriors is the alternate version of Kincar’s father, a man he didn’t know on his own version of Gorth. To defeat the evil Star Lords who have enslaved the Gorthians in this universe, Kincar will have to defeat his own father.

I suspect that I would have loved Star Gate (1958) if I had read it when I was a teenager. The idea of meeting a different version of myself in an alternate universe would probably have blown my young mind. Unfortunately, as a middle-aged adult who’s read hundreds of science fiction novels, I struggled to connect with Star Gate. It takes a while to get going, Andre Norton’s writing style here is somewhat stilted and formal, there’s far too much dialogue in many scenes, the magic (e.g., of the gates and the amulet) is dreadfully hand-wavey and, frankly, I just didn’t think it was that interesting. However, Norton deserves credit for her innovative concept (for 1958).

I suspect that I would have loved Star Gate (1958) if I had read it when I was a teenager. The idea of meeting a different version of myself in an alternate universe would probably have blown my young mind. Unfortunately, as a middle-aged adult who’s read hundreds of science fiction novels, I struggled to connect with Star Gate. It takes a while to get going, Andre Norton’s writing style here is somewhat stilted and formal, there’s far too much dialogue in many scenes, the magic (e.g., of the gates and the amulet) is dreadfully hand-wavey and, frankly, I just didn’t think it was that interesting. However, Norton deserves credit for her innovative concept (for 1958).

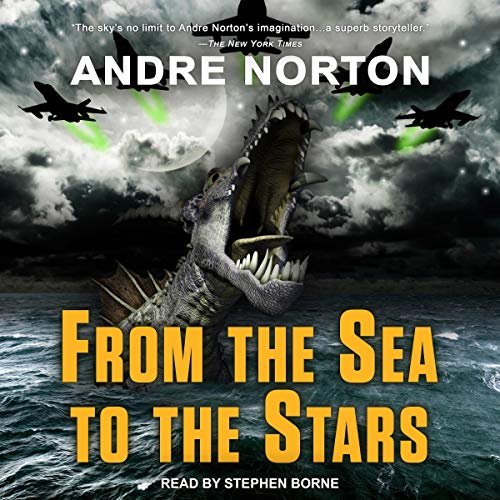

Star Gate has been printed with Sea Siege, another stand-alone novel (and one that I liked better than Star Gate), in From the Sea to the Stars which was published in print by Baen in 2009 and in audio format by Tantor Media in April 2021. Tantor’s audio’s edition is very nicely narrated by Stephen Borne.

This was always one of my favorite Norton books, so your review prompted me to break off from the middle of Crooked Kingdom to see if Star Gate suffered on a re-read now (I originally read it around 1962, I think).

I actually still quite liked it. All the science is hand-wavy, but that was par for the course in that era, not far removed from the planetary romances of writers like Leigh Brackett. I liked the native Gorthians having their own religion (or magic, looked at another way). I liked that one of the powerful Star Lords was a woman, when I had found a dearth of powerful women in the fantasy and SF in my library after having first encountered (and been impressed by) Galadriel a few years earlier in The Lord of the Rings. I found crossing the gates between parallel worlds suitably dramatic (this was the first novel that I’d read with those). I didn’t really notice there being too much dialogue in places.

There is something stilted about the style, and I think that applies to a number of Norton’s other novels (also somewhat wooden characters, in terms of them being a bit one note in their emotional concerns, when there are any). Now I wonder if some of that was the result of writing stories where the protagonist was the opposite sex from the author, at a time when most people’s conception of the sexes was very much less fluid and more stereotypical than now. (The only Norton that I can remember having read with a female protagonist was Year of the Unicorn, which I remember liking but finding confusing for long stretches.) I think most of Norton’s books (in our library) were considered “juveniles”, which was a term that mashed up mid-grade and YA by the standards of the day. A lot of Heinlein fell into that category too. So our expectations of style and characterization were probably not as high for those books.

Thanks for these comments, Paul, and for doing the re-read so you could add your opinion! It is difficult to review these Norton novels. I’ve received a lot of them recently because they’re being put on audio for the first time, which is wonderful.

It’s hard to know how to be fair to both the book (published in 1958) and the readers of our site (reading in 2021). The book might be excellent for the intended audience of its time period (which is why I made the comment that I would have loved it when I was a kid) but I also feel the need to, for today’s audience who’s reading my review, give it a rating that’s in line with all my other ratings and in the context of all the other books they could choose to read. I settled on 3 which I consider to be average.

That’s an interesting point about Norton writing a male POV, and that might be part of it, but Sea Siege, which was published a year earlier, is also written from a male POV and doesn’t feel so stilted. That novel, though, has a protagonist who’s a 20th century American while the protagonist of Star Gate lives in a society that’s more like an ancient barbarian clan, so that might explain it. Or maybe the style difference is due to where the novels were originally published, or just a whim of Norton’s.

Thanks for your thoughts!!

I’m not sure how Norton’s books would be received by younger readers today. There’s no romance and no angst and not much introspection about matters not plot-related, which I think would appear like a big absence to readers of books written now. The almost-more-primitive-than-medieval Gorth (they haven’t even invented bows and arrows!) may lend itself to a more stilted and less informal style, as you say. The style of something like Galactic Derelict, with 20th century American protagonists, is more informal. But the fact that Ross Murdock was a petty criminal and that Travis Fox is an Apache do not result in long interior monologues about the juvenile justice system or racism, as I suspect they would in a rewrite of that book today. If you were going to get critiques of society in those days, it was going to come through mini-lectures delivered by the “wise old man” characters in Robert Heinlein or John Wyndham books (which were the parts I skimmed in those books as too boring).

What little I remember, I found the few of her books I read from the late 50s to have that stilted quality, which relaxed in her later ones.

Victory on Janus may have been the last Norton I read for many decades thereafter, so I am not familiar with her later novels, especially the collaborative ones of her last years. I do seem to recall that Witch World, when it came out, was considered to be a move on her part to a type of story with more adult appeal, but I can’t recall why that was now. I think parts of that seemed a bit stilted too, and the romance aspect was so low key as to be hard to notice.