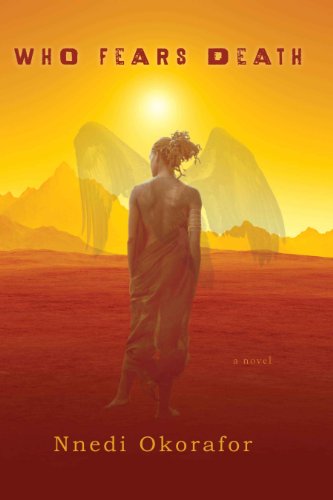

Who Fears Death by Nnedi Okorafor

Who Fears Death by Nnedi Okorafor

To be something abnormal meant that you were to serve the normal. And if you refused, they hated you… and often the normal hated you even when you did serve them.

In Nnedi Okorafor’s post-apocalyptic Sudan, there are two predominant ethnic factions: the light-skinned Nuru and the dark-skinned Okeke. Who Fears Death takes place amid a genocide that the Nuru commit against the Okeke, a campaign that (like genocides in our own time) includes both murder and rape. The mixed-race offspring of a Nuru and an Okeke is called an Ewu and treated as an outcast.

Onyesonwu, whose name means “Who fears death?”, is Ewu, the result of her mother’s rape. As a child she develops magical powers, which further set her apart from others. In her girlhood she clashes with the local sorcerer, who doesn’t want to teach her because she is Ewu and a girl. Later, as a young woman, she gathers a small group of friends and travels eastward to confront her biological father, who is himself a powerful sorcerer and the mastermind behind the genocide.

Who Fears Death can be incredibly hard to read, due to the subject matter. Okorafor depicts racial and sexual violence without flinching, and because the scenario echoes real events taking place in our own time, it hits hard. It hurts more than reading about imaginary violence in a made-up land.

Okorafor doesn’t pretty up the violence, nor does she glorify it. Scenes of violence are written in a matter-of-fact way. The writing style becomes more lyrical when describing the beautiful. One is left with the impression that Okorafor is glorifying exactly the right parts of the story. Love, kindness, magic: these things are worth celebrating. Violence just is, in Onyesonwu’s world and our own.

The setting may sound like one of today’s (or tomorrow’s) news headlines. Onyesonwu’s plot arc, though, will be familiar in other ways. Okorafor shows that a hero(ine)’s journey can fit into this bleak setting just as well as it can fit into a fairy-tale kingdom, weaving several classic fantasy tropes (such as magical training and the complex bond between mentor and student, and the ragtag band of friends who venture forth to battle evil) into the story. Onyesonwu calls to mind a really big archetype, too, one of the most famous ones: the savior-figure who brings hope to an oppressed people.

Yet she is no plaster saint. Onyesonwu is stubborn and has a temper. She feels lust and love and jealousy. She even has neuroses; she doesn’t like different foods touching on her plate. Her lover Mwita is equally fleshed-out. Her friends are drawn in broader strokes, but you’ll come to love them too, and it hurts that not all of them make it. The rest of the cast members are just as memorable. I think my favorites are Najeeba (Onyesonwu’s mother) and Luyu (one of the band of friends).

Who Fears Death is a book I will never forget, but I’m not sure I’ll reread it; it contains some scenes I’m reluctant to revisit. Several early scenes — a gang rape and a female circumcision — nearly made me abandon the book because they were painful to read. I’m glad I persisted, though; before long I was swept up in Onyesonwu’s story and couldn’t put the book down. The night I finished, I stayed up far too late turning pages, and after closing the book, I couldn’t sleep. Okorafor includes some tantalizing ambiguities, and I lay awake turning these ambiguities over and over in my mind. I love a book that makes me tear up and makes me think at the same time.

Later Update: Brilliance Audio has now released an audio version of Who Fears Death, and I recommend it with great enthusiasm. Flosnik’s voice is so gorgeous that I would happily listen to her read the phone book. Coupled with Okorafor’s prose, the effect is enchanting indeed. The one thing I will mention is that Flosnik acts out the accent that Onyesonwu might have, which means it takes a little extra concentration to follow the narrative. Then again, this is a book you’ll want to pay close attention to anyway. Who Fears Death is the polar opposite of a light read; it’s complex, thought-provoking, unsettling — and often beautiful.

~Kelly Lasiter

![]() Now that I’ve finished Who Fears Death, I don’t know what to make of it. This is Nnedi Okarafor’s first adult fantasy novel, although she has published several young adult fantasies. It is a strong, unflinching parable about tribal warfare and genocide in the Sudan. It is not a great fantasy book, and I don’t know if the ending works at all. And I don’t know if that matters.

Now that I’ve finished Who Fears Death, I don’t know what to make of it. This is Nnedi Okarafor’s first adult fantasy novel, although she has published several young adult fantasies. It is a strong, unflinching parable about tribal warfare and genocide in the Sudan. It is not a great fantasy book, and I don’t know if the ending works at all. And I don’t know if that matters.

Set in the near future after an undescribed apocalypse, Who Fears Death tells the story of Onyesonwu (her name means “Who Fears Death”). Onyesonwu is an ewu, mixed-blood, the child of a planned and organized rape of her Okeke mother by a Nuru man. The Okeke have been raised to believe that they are meant to be the slaves of the Nuru. Even the Great Book tells them that the Okeke caused the catastrophe, which appears to be ecological in nature.

Onyesonwu’s mother wants to die after she is raped by a Nuru sorcerer, but when she realizes she is pregnant she determines to live. Onyesonwu grows up in the desert, learning survival skills, until she and her mother move to the town of Jwahir. As she grows up, Onyesonwu discovers that she has extraordinary magical powers or juju. She is an eshu, a shape-shifter, and far more. She meets Mwita, another ewu, although his Okeke and Nuru parents were lovers and he is not the product of rape. Mwita is a healer and studies with the town sorcerer, Aro, who refuses to take Onyesonwu as a student because she is female. Unschooled, Onye’s growing powers become a danger to the village and Aro eventually agrees to take her on out of self-defense.

Onye’s sorcerer father tries to kill her using supernatural means, and Onye dreams of revenge, but her destiny is far greater than the death of one sorcerer. With Mwita and a group of female school friends, Onyesonwu heads east, to Durfa, the town where her father lives, because he is gathering an army and preparing to destroy all Okeke.

Okorafor is direct in her descriptions of weaponized rape, female circumcision, institutionalized inequality and codified violence. Daily life in Onye’s village is well-described, although it is not particularly post-apocalyptic. Okorafor does not spend time trying to explain or understand the tribal hatred between Nuru and Okeke, or even why sexual inequality is so prevalent. These are merely the conditions of life in Onye’s world. In Jwahir, Onyesonwu’s ostracism is taken for granted by Onye herself.

Onyesonwu is a flawed sorcerer but a great character. She is emotional and impulsive, with a bad temper and a deep well of self-doubt. Unlike sorcerers in the European-American fantasy tradition, Onye has a strong, loving mother and stepfather and a lover who is loyal. She and Mwita squabble constantly, but it is not about sexual jealousy; it is about the reversal of roles. Mwita is a healer and Onye is a sorcerer, a function usually reserved for men. Mwita also fears Onye’s impulsiveness, since he has also been Aro’s student and knows more about juju than she does.

Juju does not protect Onyesonwu or her friends from the violence of villagers as they head west; nor does it stop the bickering and distrust among her friends. Still, she does reach Durfa and confront her sorcerer father. The confrontation is dramatic, but defeating her sorcerer father is not her true destiny, and Onyesonwu cannot rest until she finds a Nuru seer who holds an artifact that has meaning for her, and for the Okeke people.

This is a powerful story and there is a lot to like. I like Onye and her friends; I like that the book is set in Africa and is about Africans, not European-Africans or transplanted Americans. Okorafor deals with difficult issues courageously for the most part, but there’s an element of the book that looks like fantasy-wish-fulfillment, and that jars me, and makes me distrust the doubled ending.

Early in the book the impulsive Onyesonwu makes a decision to go through with the Eleventh Year Rite, female circumcision. Her mother and stepfather do not support this practice, but Onye decides that she is already a source of shame to her mother, and doing this will keep her from being more of one. This decision has catastrophic results. It will not only affect Onye’s life and happiness, it can have a devastating effect on her juju. One magical being she meets during her magical initiation flat-out tells her that she will not survive it because she has been “cut.” The Eleventh Rite scene is shocking, and Okorafor makes it clear that the female elders wholly support genital mutilation. Later, though, Onye undoes what was done to her. Later still, she heals her school friends, and that scene shows intense physical and emotional exertion. In the first sequence, though, Onye basically wishes she were whole, and she is. It is too easy and feels like Okorafor wants to have things both ways: to point out the devastation of female circumcision and still let Onye have satisfying sex with her true love. Thus, when the book has a doubled ending (not unlike John Fowles’s doubled ending in The French Lieutenant’s Woman, which I also distrusted), I have to ask myself whether it is just another way of having both the meaningful ending and the happy one.

Perhaps some of my skepticism comes from Okorafor’s young-adult background. The book has simple sentences, brief chapters and lack of foreshadowing, particularly of the important peacock symbol. These are aspects often found in YA novels. Generally, in a YA novel I expect to see the writer try to give the main character happiness even when the events of the story do not logically lead to it.

In the end, I’m not sure my concerns really matter. If you read Who Fears Death as a parable rather than a fully-realized fantasy novel, it is moving and thought-provoking. It easily earns four stars. Can women really change their destinies in this part of Africa? Can their power stop the genocide? Can anything? It seems doubtful, but at the end of Who Fears Death, both the Okeke and the reader are left with a precious magical gift: hope.

~Marion Deeds

Great review. My thoughts on the ending were kind of like this: is the happier ending really what we should want? Does the happier ending undo what good this character managed to do? If we mentally “pick” that ending, are we picking our own comfort but undoing the sacrifices made? It made me thinky enough to bump it up a star.

Can’t say you made me push it up in my TBR pile but reading about it again certainly makes me more aware that it is still in the pile.

I actually loved the two endings in Fowles book but not having read Who Fears Death yet I can’t make a comparison.

There are a few books I’ve read in recent years that are powerful books, highly recommended, but are the furthest thing from comfortable reads and that’s their point. This is one of them. Octavia Butler’s “Wild Seed” is another, and I made that comparison when I did my own review of “Who Fears Death.” The books are amazing, but they shift your worldview around and force you to look at things most people would rather turn their head from and tsk about instead of actively confronting. I feel a bit richer from having read this book.