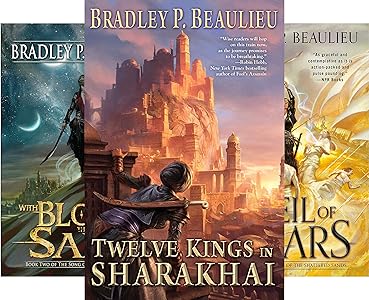

![]() When Jackals Storm the Walls by Bradley P. Beaulieu

When Jackals Storm the Walls by Bradley P. Beaulieu

You had me at “The Story so Far.”

You had me at “The Story so Far.”

Really. It was all gonna be good after that.

“The Story so Far.”

Say it with me: “The Story so Far.”

Sweet Nana jam on toast, that curls the toes.

“The Story so Far.”

That’s how When Jackals Storm the Walls (2020), Bradley P. Beaulieu’s fifth novel in his THE SONG OF THE SHATTERED SANDS series begins, and nothing, nothing endears me more to a sequel, particularly a third or fourth or seventh book in a series, than a “here’s what’s happened up to now” prologue. Seriously, authors, publishers, gods of fiction — is it honestly all that hard? Isn’t this what staffers are for? Interns? Underfoot children? “The Story so Far.” No more dredging up shadowy memories from a year or two earlier trying to recall who lived, who died, and who died and came back then died again. No desperately Googling for synopses. And certainly no rereading of the prior books each time a sequel came out (thank you George R.R. Martin for curing me of that particular fetish).

“The Story so Far.” My prologue and I are going to be alone for a while now.

OK. Luckily, the prologue is just one of the many good things about When Jackals Storm the Walls, which is another strong installment in this quite good series (I’m going to assume you know the characters and basic plot). Everything is converging as we near the end, with the deposed Kings of Sharakhai, Ceda and her group of avengers, a rebel host, the new kings, the foreign powers of Mirea and Malasan, Queen Meryam, the Enclave, Anila, Davud, Ramahd, Hamzakiir, several gods, and others scheme, ally, double-cross, and battle both in the desert and in the city until they all come together in a clash for control of Sharakhai. It’s a complicated plot with a number of POVs, but Beaulieu handles all the shifts deftly, making it easy to follow the narrative so neither the complexity nor the number of characters becomes a barrier to engaging with the story.

Bradley P. Beaulieu

That story builds nicely in several ways. One is that the early conflicts tend to be more personal or limited to a few characters (Emre taking on Hamid, for instance), and while small fights break out, the early part focuses more on the various chess moves as everyone tries to put their plots into place or hinder the schemes of others. The action becomes both more frequent and larger as the story goes on, though, culminating in that aforementioned clash where nearly everyone is in attendance and fighting someone else. Another way the narrative broadens is that what first appears to be merely a battle for political control (of the city, of the desert) turns out to be in service to something far larger and more cosmic, though I won’t say more about that so as to avoid spoilers.

The characters are another strong element, as they have been throughout. One of my favorite aspects of this series is how Beaulieu began with a clear “hero” in Ceda, but has been happy to let a number of others share significant stage time with her, creating more of an ensemble story, rather than one dominated by a single character to the detriment of the others. Brama’s inner conflict, Meryam’s backstory (told through a series of interwoven flashbacks), Emre’s continued growth toward a leadership role, King Ihsan’s attempt to use Yusam’s prophecies to thwart the gods — each of these plot lines are engaging in their own right even as they move the entirety of the narrative forward. And Beaulieu continues to shade the “bad” characters with more hues of grey, humanizing them so they become far more interesting than central casting’s “Stock Power Hungry Villain Type C.”

The exploration of subjects like forgiveness, responsibility, power, action versus inaction in the face of immorality, the problem that “suffering can arise from the kindest of acts and good can flow from the manipulations of evil men” all add some depth. And some relevant timeliness, as when Ceda thinks:

Men like Hamid would never admit it, but Sharakhai was a melting pot. So was the desert … Their culture was not pure, as some would claim, nor had it ever been. Purity had always been a fantasy, a way to exert power over others … the lives of the desert people had been enriched by neighboring lands.

The prose is vibrant and detailed, the settings and events painted in vivid sharpness. One excellent example is during an operation involving boring into a character’s skull — the visual description is certainly effective, but what lifts the whole scene up a notch is when Beaulieu tells us “In all his preparations, he hadn’t thought to oil the drill. It shouldn’t have mattered, but the sound kept going, on and on, and it was driving her mad.” That’s a great tiny detail that makes the scene all the more horrifying.

As with some of the prior books, there were a few places where pacing seemed to lag a little, and the book felt it could be trimmed somewhat, but I’d say these occurrences were fewer than in the first few novels and really, it’s more an observation than a complaint as the book never dragged or felt all that overly-long. I not only happily read it in a single sitting but did so twice because so much time had passed between my first reading and my review writing. I’d say that’s a pretty sign of quality engagement.

When Jackals Storm the Walls resolves several plot points completely, and ends with a nice tease for the next, which I’m eagerly awaiting. All, once more, with feeling.

“The Story so Far.”

Ahhhh.

I keep meaning to get back into this series, and every time you review a new book, that only reminds me how much I enjoyed the books I’ve read!

I agree. This was a very good book, perhaps the best in the series so far. So many characters but whose story lines were so compelling. The world this author has created is amazingly alive while being, at least for me, exotic. However, I have to say, I was upset that this book isn’t the end of the story. It sure seemed like it was – and then it wasn’t! Aargh. And yes, having the summaries means I don’t have to take notes on what is a very complicated plot. Thank you!