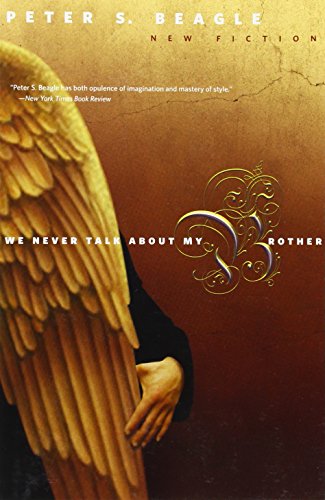

We Never Talk About My Brother by Peter S. Beagle

We Never Talk About My Brother by Peter S. Beagle

We Never Talk About My Brother, published by the small but estimable Tachyon Press, is a collection of ten of Peter S. Beagle’s recent stories. Eight were previously published from 2007 through 2009, demonstrating that Beagle has been as productive in his late 60s as he was at the age of 19, when he wrote A Fine and Private Place. Certainly his late work shows a mature intellect and imagination, as well as a perspective on his youth, that flavors his fiction with nostalgia, regret and a deep appreciation for life.

The title story is told by the narrator to a reporter who comes searching for news about the narrator’s brother, who used to be a famous news anchor. Esau Robbins, the news anchor, disappeared entirely from the scene years before. His brother Jacob knows why and is willing to tell the story. It seems that Esau didn’t exactly report the news; he made it. He made it by reporting it. He was a sort of Angel of Death, telling tales of horrible doings and thereby causing them to be done. How does one stop such a man? Jacob figures it out, and thereby hangs his tale.

“We Never Talk About My Brother” is a sharp, tight story, but for my taste, “Uncle Chaim and Aunt Rifke and the Angel” shows a lot more of that mature intellect and imagination that I spoke of earlier. Beagle states in his introduction that the story is one of only a few he has told that draws specifically from his New York Jewish childhood, and it makes me long for a memoir tinged with fantasy from him. This story is about an angel who comes to pose for his Uncle Chaim, who is an artist. The angel simply shows up one day and announces that she is his only model now — and a great model she proves to be, too, able to hold a pose seemingly forever. But there are a few problems. For one thing, almost no one else can see the angel except in Chaim’s paintings (though the young narrator of the tale can). For another, there’s something just plain weird about this particular angel. We find out what that weirdness is, and experience an unusual act of kindness and bravery, in the climax to this gentle, lovely story.

I’d come across “The Last and Only, or, Mr. Moscowitz Becomes French” before in Eclipse One (2007), an original anthology of science fiction and fantasy edited by Jonathan Strahan. It’s about a Jewish-American man who slowly becomes French after visiting France on his honeymoon. He loses his ability to speak or read English, becomes very rude to those who speak (or attempt to speak) French with accents of which he doesn’t approve, and, ultimately, becomes more French than the French themselves. It’s a strange story that should be simply funny, but is ultimately melancholy.

I loved “Spook,” about a duel by bad poetry. Beagle says in his introduction that he can’t wait to record the audiobook version, and I can certainly see why. I don’t think I’ve ever read worse poetry in my lifetime, and I say that as someone who wrote sad, sad poetry about unrequited love at the age of 16 and read it again at the age of 40. I hope very much never to have to read the poetry of Theophilus Julius Henry Marzials ever again (sample lines: “And the shrill wind whines in the thin tree-top/Flop, plop/A curse on him”).

“Chandail” is set in the universe of The Innkeeper’s Song, and is about Lal’s encounter with one of the title species. It is an accomplished story in which two creatures completely alien to one another reach an accommodation and even, perhaps, something more. “By Moonlight” is a conversation between a highwayman and a preacher who was once Titania’s lover, and seeks to be once again. “King Pelles the Sure” is an antiwar tale about a king “who dreamed of war,” and thought he could have just a little, manageable one, just big enough to ensure that he would be remembered as a hero; “Nobody is ever remembered for living out a dull, placid, uneventful life,” he complains. He comes to rue those words. “The Unicorn Tapestries” is a poetry cycle about the tapestries hanging in The Cloisters in Manhattan’s Fort Tryon Park. “The Stickball Witch” is a slight story about children playing on the streets of the Bronx, and their adventure one fine day with the neighborhood witch — or at least the poor immigrant widow in the neighborhood that they all feared, for some unknown reason (that is, unknown even to them).

“The Tale of Junko and Sayuri” is my least favorite story in the book, about a man who works his way up in a Japanese court with the help of his mysterious wife. I was not convinced by the setting or the characters, and nothing about the tale spoke to me of Japan; it could as easily have been set in England if the names were different. Perhaps I like my Eastern mysticism to be a bit more mystical, but this story just fell flat for me.

This is one of those collections that I read nearly straight through, barely pausing to set the book down. Many single author collections tend to have much of a sameness about them, I have discovered, and suffer from that sort of reading. Not Beagle; not this collection. The stories are varied in theme and tone, though alike in craftsmanship.

This slim volume is not only worth reading, but worth adding to your library, for you are likely to find yourself returning to these stories again and again. If you are a reader, you will find sheer pleasure in them on each rereading. If you are a writer, you will explore them to find out just how Beagle does it. He is one of the most able writers of the fantasy short story working today.

I find if I take every Trek reference out of them (the title, the character names, the ship names, etc.),…

I loved this deep dive into Edwige Fenech's Giallo films! Her performances add such a unique flavor to the genre.…

It would give me very great pleasure to personally destroy every single copy of those first two J. J. Abrams…

Agree! And a perfect ending, too.

I may be embarrassing myself by repeating something I already posted here, but Thomas Pynchon has a new novel scheduled…