Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

Watchmen by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

What if superheroes were real? I mean really “real”: what if they grew old and got fat, had spouses and families, carried emotional baggage (sometimes a serious psychosis), and just generally had to deal with everyday life? These super-heroes aren’t inherently all good, either. Just like public servants — police, politicians, doctors, etc. — many begin with the best intentions, but some become jaded and others are only motivated by self-interest from the start. In other words, if superheroes were real, they would be just like us, more or less.

Also, what would an ultra-powerful superhero really be like? A person who understands quantum theory as easily as we chew gum, and is so powerful that he can move through the space-time continuum, be several places at once, and alter sub-atomic structure with a mere thought? Can you imagine how scary it would be for a god to live among us? Someone whose very citizenship in a particular country gives that country an unbeatable advantage over the rest of the world?

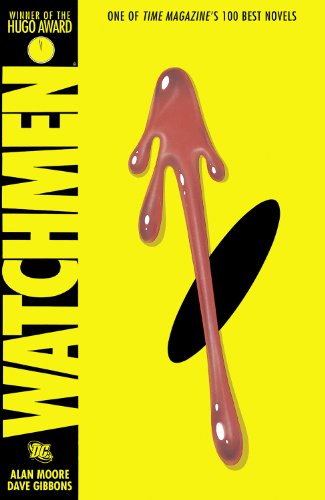

On the surface, this is the premise for Watchmen, and Watchmen was the first work of its kind to humanize superheroes this way, but it’s also much more. There are good reasons this graphic novel, or comic book for adults, won a Hugo and was picked by Time magazine as one of the 100 best English-language novels since 1923. (To any literary snobs out there who’ve talked trash about comics and the like: In your face, Dude!)

Alan Moore made superheroes into real-life people. Then he put these heroes in a paranoid world on the brink of a nuclear holocaust, a world where a symbolic clock that tracks doomsday as 12:00 is currently ticking down to the last few precious minutes. Does that world sound familiar? It should. It was Earth circa 1980’s.

This reviewer recalls those times all too well, as I imagine most anyone who lived through the Cold War can. I was mostly just a kid then, but it still seemed inevitable that sooner or later the USA and U.S.S.R would have at each other and the world be damned. In fact, I was in the Army at the time the Watchmen comic was running, in ‘86 thru ‘87 (which is probably why I missed it then) and we were training with the Soviets in mind as our enemy. So I found Watchmen to be pretty much… terrifying.

Mr. Moore’s insight into modern society and how fragile our world is, unfortunately, rings all too true. It’s enough to keep you awake at night. There are probably one or two people left that haven’t read Watchmen or seen the movie yet so I won’t give away spoilers, but if you take into account the time Watchmen was written and what came to pass years later, it’s even a little prophetic.

In a graphic novel, the illustrations tell as much, if not more, of the story than the words. So it’s crucial that the artist realize the writer’s vision and be inspired by it enough to bring the action and emotion to life. When the writer and illustrator are a perfect match, a graphic novel or comic book becomes a thing of magic. Moore and Dave Gibbon accomplished this with Watchmen.

Even more than the actual imagery, the coloring and shading make this story jump out of the book. Flashes from lightning or explosions almost made me blink. I could practically feel the dampness of a rain-slick street. A horrifying facial expression of a character so angry that he’s about to explode with violence all but makes the reader instinctively prepare to flee. Don’t overlook the smallest details of each panel. They will be meaningful later.

I have enjoyed a few other graphic novels more than I did Watchmen. But nothing I’ve ever read has been as frightening as the decision the characters face at the conclusion. It’s the kind of decision that, if it really happened, we wouldn’t want to know about. And I’ve never read anything that realizes life’s place in the grand scheme of the universe like Watchmen does.

I’m amazed that comics, the very medium that introduced me into the fascinating world of books, turned out to be the medium that produced the most profound book I’ve ever read.

~Greg Hersom

What more can be said about this brilliant, game-changing graphic novel from 1987? It challenged, deconstructed, and redefined the superhero story to the point that it’s hard to imagine any comic book writer not being fully cognizant of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen when they put pen to paper (or finger to keyboard). Despite it coming out almost 30 years ago, it’s remained continuously in print with its iconic yellow smiley face with a drop of blood. Most fans consider it the greatest graphic novel ever written, and Time Magazine named it one of the 100 best English-language novels. I’m not an expert in comics or graphic novels, but I wouldn’t disagree. In fact, until recently it was the only graphic novel (other than Frank Miller’s SIN CITY series) I’d read in the past 25 years despite a life-long love of SFF.

What more can be said about this brilliant, game-changing graphic novel from 1987? It challenged, deconstructed, and redefined the superhero story to the point that it’s hard to imagine any comic book writer not being fully cognizant of Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchmen when they put pen to paper (or finger to keyboard). Despite it coming out almost 30 years ago, it’s remained continuously in print with its iconic yellow smiley face with a drop of blood. Most fans consider it the greatest graphic novel ever written, and Time Magazine named it one of the 100 best English-language novels. I’m not an expert in comics or graphic novels, but I wouldn’t disagree. In fact, until recently it was the only graphic novel (other than Frank Miller’s SIN CITY series) I’d read in the past 25 years despite a life-long love of SFF.

I think Watchmen addresses a lot of the reasons WHY I wasn’t interested in comics all that time. They’re right next to SFF books in the bookstore, and they feature stories that are mostly fantastic in nature. Not only that, but they having amazing cover artwork that really catches the eye. So what’s the problem? I guess my memories of comics are from the mid-1980s, and back then when I read G.I. JOE and TRANSFORMERS, I’m pretty sure I was just brain-washed by Hasbro. The stories weren’t great and neither was the artwork. I was never really interested in SUPERMAN, BATMAN, THE AVENGERS, X-MEN, etc. The stories seemed too simplistic (just a preconception – I didn’t actually read them) and filled with KAPOWS and THWACKTS ala Adam West’s classic Batman TV series. Once I was actively reading 500-page SFF novels as a teenager, I simply assumed that comics COULD NOT achieve the same depth of story and character that books can. Seriously, a single issue is maybe 25-50 pages, right? Sure, there are long-running story arcs, but that’s not the same as a stand-alone novel.

However, over the last two decades Hollywood has discovered what an absolute treasure trove comic book superheroes are. They’re ready-made franchises with thousands of episodes and story-arcs, iconic characters that everyone knows, and tons of product tie-in potential. It’s been a bonanza for MARVEL and DC, the two industry heavy-hitters. And most people now know who Frank Miller and Stan Lee are. One of the biggest trends of more recent years has been the increasingly dark and complicated nature of super heroes. You need look no further that the original Tim Burton versions of Batman from the 1990s to the incredibly dark vision of Christopher Nolan’s DARK KNIGHT series.

It’s very likely that Watchmen (and Frank Miller’s DARK KNIGHT reinterpretation) deserve a lot of credit for that trend toward dark, complicated, and twisted superheroes, to the point where the term “hero” comes into question. In Watchmen there may be a lot of characters dressed in costume, but you’d be hard-pressed to identify the “superheroes” among them. In fact, it’s fair to question whether they are “super” at all. The characters of Watchmen are all attracted to the idea of the “superhero”, that person with extraordinary abilities who uses them to fight crime and injustice. And while there is certainly one character (Doc Manhattan) who has incredible powers far beyond most superheroes, he is distant and uninvolved in human affairs despite his human origins and love interests.

Watchmen asks the disarmingly simple question, “What is a superhero, and why would anyone want to be one?” I mean, they’re dressing up in tights and spandex and going around beating up criminals. That’s not a “normal” career. In fact, how do superheroes earn income? Do they pay taxes? Do they take those costumes to a dry-cleaners or hand-wash only? The more you think about it, the more ridiculous it sounds. We all know that crime pays, but what about crime-fighting? You don’t get much besides the keys to the city, a handshake from the mayor, and the thankful smiles of a grateful citizenry. So wanting to be a superhero is something internally-driven. Even then, why? The thrill of anonymity, perhaps, or the desire to become someone more exciting than the everyday prosaic middle-aged tax accountant with the nice house, pretty wife, 2 cars, golf membership, kids and a dog. Then again, maybe you really have a grudge against crime and want to champion the weak. You might have been the victim of a terrible crime and vowed to dedicate your life to protecting people from such a fate. Or maybe it just seemed like a cool idea and you didn’t have any other particular plans.

There are so many themes explored in Watchmen that you could easily teach a college lit course about it, and there are in fact such classes, though I was never fortunate enough to take one. Our very own FanLit comic expert Brad tells me he has taught this text many times to many of his students. It’s guaranteed to produce a lot of amazing discussions, I’m sure. It’s also clearly intended to be read multiple times, and I’ve read it twice. So to avoid driving myself insane trying to cover every aspect of this multi-layered work of art, I’m going to stick to the central theme of “what is a superhero, and why be one?” One of the great aspects about Watchmen is that it is a deeply moral work that concerns itself with justice, free-will, evil, despotism, hubris, and yet it never spells out its agenda, or cheapens its characters by making them mouth-pieces for the author’s pet ideas. Of course each character explores aspects of the superhero concept, but none of them fit that Golden Age stereotype with bulging muscles, a square jaw and deep voice, and an untiring drive to fight crime.

Below is a basic synopsis of the main characters of Watchmen. There is an earlier set of superheroes that arose in the 1940s and 1950s in this alternate reality, but I won’t even attempt to describe them. They form the basic conceptual framework for superheroes, but I’m most interested in the characters who drive the main story arc in the 1980s:

THE COMEDIAN (Eddie Blake): This guy is a big, cynical and amoral thug. He revels in conflict and violence – although ostensibly falling under the “superhero” rubric, he quickly finds he has no problems taking down Latin American dictators as a government operative. He also takes great pleasure in killing “badguys”, which in Vietnam basically meant everyone opposed to US forces. Machine guns, flame throwers, fists & kicks, it’s all good to the Comedian. Because to him life is one big, ironic joke. The joke being that you’re a sucker if you believe there is any justice or purpose in our lives. The strong take what they want, and the weak don’t. Who would you rather be? His philosophical differences with Nite Owl are fascinating, and his emotional dealings with both iterations of Silk Spectre show his best and worst sides.

RORSHACH (Walter Kovacs): Rorshach sees the world in black and white, a simple dualism of good and evil. He was bullied as a child, railed against his prostitute mother, and developed an intense and smoldering hatred for the worst aspects of humanity. This hatred is so all-consuming that it leaves little room for sympathy for the common man. As a form of self-validation, Rorshach spends all his time hunting down criminals of the streets, beating and killing them without mercy. Those that hurt children in particular draw his ire. Where he struggles is finding room for anything that doesn’t fit his ultra-narrow worldview. There are no grays in his moral universe, only black and white shifting but never mixing, like his mask. He is an angel of vengeance, a vigilante with the noblest intentions. But is he a hero, or a vigilante? Does purity of intent and purpose justify his ruthless killing? Readers who sympathize with Rorshach should examine their politics in other areas as well. Maybe he is right, maybe humanity is unworthy, but what an awful way to live each day.

NITE OWL (Daniel Dreiberg): The modern-day Nite Owl is actually the second to wear the costume. Dan Dreiberg inherited a lot of money from his banker father, and has a deep love for flying machines and animals. One suspects he wishes he could just watch owls all day and fly with them. He was the crime-fighting sidekick of Rorshach and the Comedian, but has hung up the wings to do…nothing. His life seems fairly pointless after quitting crime-fighting. He tinkers in his place alone, only reliving the old times with weekly beer sessions with the senior Nite Owl. His characters is pretty wimpy until he catches Silk Spectre on the rebound from Doc Manhattan, at which points things spice up a bit. Although he is perhaps the most normal of the Watchmen, he is hardly heroic.

OZYMANDIAS (Adrian Veidt): After retiring from crime-fighting, Adrian has become an extremely-successful businessman who is also “the smartest man in the world”. He is incredibly athletic and handsome, skilled at hand-to-hand combat, and markets his own training program. In other words, he’s that guy from high school everyone hates and envies. He runs Veidt Enterprises, and is something of an unholy combination of Tony Starks (rich, charismatic, brilliant) and Donald Trump (complete egomaniac, superiority complex). Adrian’s biggest problem is that he is so superior to the average man that he can’t help looking down on him. This causes him to hatch an elaborate and evil master-plan that any super villain would be proud of.

SILK SPECTRE (Laurie Juspeczyk): Laurie is the weakest character in the group, and probably Moore’s least impressive creation. It seems clear that he had trouble coming up with a viable female superhero. One wonders what would happen if he had instead tried a Harley Quinn-type villain with some charm. Laurie’s mom was Sally Jupiter, the original Silk Spectre, who had some ties to the Comedian in the past. Laurie grew up idolizing her superhero mom, and so has followed in her footsteps. However, her main purpose seems to be the love interest for Doc Manhattan, his last emotional connection to humanity.

DOC MANHATTAN (Jon Osterman): He is by far the most interesting of Moore’s creations. Doc was a promising scientist studying particle physics. When an experiment goes terribly wrong, he is initially atomized before finding a way to reconstruct himself, atom by atom, and become this all-powerful blue man-figure with a great physique and disdain for clothing. He still stays with his girlfriend at the time, but the US military increasingly uses him for geopolitical power politics, particularly to maintain a precarious edge over the USSR in an alternate version of the Cold War (perhaps the only plot element that feels overly 1980s). The stresses of being used for his powers (including the Vietnam War) despite his growing disillusionment with the petty conflicts of humanity eventually spoils his relationship, but instead he shacks up with the Laurie, the younger iteration of Silk Spectre. She too suffers from his clumsy inability to understand the emotional needs of another human being, let alone a lover.

We see Doc Manhattan wield almost unlimited powers over matter, creating and destroying at will. And yet when he gets completely fed up with the tawdry squabbles of mankind, he ditches Earth and heads to Mars for some R&R, meditating and creating a fantastic geodesic artifact to occupy himself. What we see in him is a far more realistic portrayal of what an all-powerful being is likely to behave like. Unlike Jehovah of the Old Testament, who is constantly punishing humanity for every little transgression like a petulant child smashing his toys, Doc Manhattan can’t be bothered with people. Seriously, why would you when the world of tachyons and quarks are so much more interesting.

The other fascinating thing about Doc is that he lives in a quantum universe, so he experiences time as a continuum, seeing past, present, and future simultaneously. Moore really nails the mechanics of avoiding time paradoxes: my favorite pet peeve involves that hairy old chestnut “going back to change things”. It’s very simple, really: you can’t change anything because time already exists and is fixed. You can look up and down the line, but don’t think you can change it. This means that Doc knows the future but can’t do anything about it. That makes it pretty frustrating when Laurie tries to have conversations with him. It also makes the universe a very deterministic place and discounts the concept of free will. Even if we are free to make our choices, they have already been made in the quantum universe.

So the clever reader must have noticed, where are all the super villains, the Jokers, Penguins, Magnetos, Green Goblins, Lex Luthors, etc? Haven’t figured it out yet? There are no super villains in the real world, silly, that’s just in comic books. And Watchmen is not some pulpy wish-fulfillment fantasy. It’s about the world you and I live in, filled with well-intentioned but imperfect people with passions, aspirations, dreams, psychoses, problems, frustrations and occasional triumphs like everyone else. It’s just that some of them wear costumes, that’s all.

Dave Gibbon’s Artwork/Tales of the Black Freighter:

The comic medium is distinct from novels because of the artwork, and the artwork of Watchmen is truly special. It is an example of total artistic commitment by both author and artist to achieve something never before seen in the genre. Dave Gibbons was given extremely detailed instructions by Moore for each frame, and they agree to use a 9-panel layout to give a uniform structure, unlike the more common variable size/number of panels. Gibbons inserted an incredible number of details into each panel, especially the various textual media found throughout the book, such as newspapers, graffiti, TV screens, book covers, etc. Much of these visual clues point to the impending countdown of the doomsday clock ticking down to nuclear Armageddon. There is also the pervasive metaphor of the smiley face button, which the Comedian uses for ironic purposes, but I see the iconic image of the drop of blood covering the face as a clever metaphor for how the innocent ideal of comic book heroism is tainted by the violence and death of the real world. There is such a wealth of visual details in the book, not to mention the book-within-a-book horrific pirate story called Tales of the Black Freighter, that I have never seen in graphic novels before. And the crowning touches are the inserts between chapters of excerpts from the autobiography of Hollis Mason (the original Nite Owl) that describe the origins of the first generation of superheroes (the Minutemen) in the 1940-50s, articles describing the history of Doc Manhattan and his impact on the Cold War, a description of the artists involved in early pirate comics, police documents of Rorshach, snippets from the New Frontiersman newspaper, even super-realistic notes from a Hollywood producer corresponding with Sally Jupiter, the original Silk Spectre. The verisimilitude and depth achieved with these interludes gives Watchmen the feel of a completely three-dimensional experience, encompassing storyline, character history, story-within-story, and visual elements.

Watchmen Film (2009, directed by Zack Snyder)

It was inevitable that a graphic novel as epic and complex as Watchmen would attract the attention of filmmakers. However, as is frequently a case with such a dense and complicated storyline, finding the right people to come up with the right screenwriters, producers, directors, and studio is an extremely difficult task. So the film got bounced around Hollywood for years and years, with directors and producers as diverse as Joel Silver, Terry Gilliam, Darren Aronofsky, and Paul Greenglass before the stars aligned and Zack Snyder was given the nod thanks to his distinctive visual work on Frank Miller’s 300.

It was inevitable that a graphic novel as epic and complex as Watchmen would attract the attention of filmmakers. However, as is frequently a case with such a dense and complicated storyline, finding the right people to come up with the right screenwriters, producers, directors, and studio is an extremely difficult task. So the film got bounced around Hollywood for years and years, with directors and producers as diverse as Joel Silver, Terry Gilliam, Darren Aronofsky, and Paul Greenglass before the stars aligned and Zack Snyder was given the nod thanks to his distinctive visual work on Frank Miller’s 300.

The film version has a big budget of $120 million but hardly any major household names. The costs mostly involve the elaborate sets and special effects. The Watchmen graphic novel served as the storyboard. Visually, fans of the original will immediately recognize scene after scene from the comic, and Snyder did an excellent job bringing the dark and dystopian tone of the book to the screen. He also brings strength in the kinetic and violent action sequences, especially with sudden switches to slow motion in mid fight. The faithful careful attention to details extents to the beautiful geodesic glass artifact constructed by Doc Manhattan on Mars. It looks exactly as I envisioned it from Dave Gibbon’s artwork.

The acting isn’t quite as strong as the visual work, but I was satisfied with the fiercely uncompromising Rorshach and cynical Comedian. Nite Owl was played accurately as a fairly milquetoast aging superhero who has almost forgotten his glorious crime-fighting past, but I enjoyed his character when he finally takes out the Owlship with Silk Spectre to break Rorshach out of prison. The weakest actor by far played Silk Spectre, but a lot of my dislike may be more towards the character than the performance. Although Doc Manhattan is portrayed using CG, the actor Billy Crudup shot the scenes with the other actors. I like his cool and distant voice, it worked well with character.

The acting isn’t quite as strong as the visual work, but I was satisfied with the fiercely uncompromising Rorshach and cynical Comedian. Nite Owl was played accurately as a fairly milquetoast aging superhero who has almost forgotten his glorious crime-fighting past, but I enjoyed his character when he finally takes out the Owlship with Silk Spectre to break Rorshach out of prison. The weakest actor by far played Silk Spectre, but a lot of my dislike may be more towards the character than the performance. Although Doc Manhattan is portrayed using CG, the actor Billy Crudup shot the scenes with the other actors. I like his cool and distant voice, it worked well with character.

Alan Moore refuses to have any involvement with film adaptations of his works, so writers David Hayter and Alex Tse were free to reshape Watchmen into something that could fit within the confines of a 2 ½ hour film. I think the two best decisions made in cutting down the story include removing all the Tales of the Black Freighter from the film, since this really was intended for readers of the comic as a tribute to pirate comics, and wouldn’t have worked in the movie as it lacks any direct connection with the story. I also liked how they and Snyder used the opening frames of the movie to depict the early Minutemen superheroes in technique that allows real-life stills to mimic photographs, but still retain some motion. This way viewers get a taste of what the early superheroes looked like without having to devote lengthy screen time to their backstories.

The biggest change made was to the final climactic scenes in Antarctica as Rorshach, Nite Owl, and Doc Manhattan attempt to foil Ozymandias’ evil master-plan. I actually thought this was overly complex and difficult to understand in book. [highlight the following text if you want to read a spoiler] Teleporting some freakish alien monster, whose brain was cloned from a human psychotic, into New York City in order to use the massive psychic shockwave from its brain to kill half the city? And this will somehow unite the warring superpowers against a common enemy? Perhaps this was a conscious dig by Moore at the implausibility of master plans by comic book villains? Since the rest of Watchmen seems very realistic within the alternate reality created by Moore, this part of the story struck me as farfetched. So I was actually quite happy when the film version made Ozymandias’ plan more concise and sensible. By simulating nuclear attacks in cities around the world and framing Doc Manhattan for it, this would be more likely to unite the world against Doc Manhattan, thereby completely alienating him from humanity and also eliminating him as a rival to Adrian Veight’s plan to rule the world in the aftermath. [end spoiler]

I’ve heard that many Watchmen fans really hated the film version, but I didn’t feel that way at all. While the film of necessity had to shed many of the side and back stories and incredible background details that make the graphic novel so rich, I think they retained the important aspects of the storyline and focused on them. I also think the film piqued the interest of many viewers to give the graphic novel a try, directing new blood to the comic/graphic novel genre. There are so many disastrous comic book adaptations out there, so Zack Snyder’s film is much better than that.

~Stuart Starosta

Amen. Watchmen is a classic for the ages. It’s a cliche, but this is one of those books where I discover something new every time I reread it. It blew my mind when I finally noticed that the “Watchmaker” chapter is a perfect mirror – the last frame is a reflection of the first one, the second to last reflects the second, and so on (similar to how the very first frame of the book echoes the last one!). As you wrote, every single detail in the book matters. It’s a work of genius.

That is one of the things about a well-done graphic novel. There is so many little details left unsaid in the artwork.

Plus with Watchmen, there is a lot of little stories that are taking place outside the main plot. Like I love the dialog between the Newsstand owner and the kid, that hangs-out and reads a comic books without ever paying for them and how their relationship develops. At first the newsstand owner was obnoxious to me but as the story goes, I really start to like the guy. It showed how deep down there can be more good in people as individuals than what we generally see on the surface.

Watchmen, isn’t my favorite Graphic novel, -that would be Frank Miller’s Sin City books-, but it really struck a cord with me.

One of the things I love is the way Moore interweaves two story lines by combining the imagery from each. e.g. from the newsstand example you mentioned, the way the black sails against the yellow sky in the comic book morph into the black and yellow sign for the radiation shelter. Or the way the captions connect to the flash backs on the first pages of the book: “Ground floor coming up.”

Damn, now I want to reread it again.

That’s one of the elements I found scary. Because the reader that is reading Watchmen, which has some very true elements of our real world, is reading about a kid, who is reading a horror comic, that is symbolic of what’s going on in the world of Watchmen.

It almost gave me that effect of; who is to say, what I was reading in Watchmen, couldn’t be symbolic of something that’s really happening now. It was just a little creepy feeling.

Wow, Stuart, what a review! Hat’s off!