![]() Vampires of the Andes by Henry Carew

Vampires of the Andes by Henry Carew

Just as it’s patently obvious that “You can’t judge a book by its cover,” it seems to me that one might justifiably add the statement “You can’t judge a book by its title, either.” Case in point: the novel that I recently experienced, Vampires of the Andes. Now, with a title like that, one might automatically be led to assume that this would be a rather pulpy, empty-headed affair; a simply written story, perhaps concerning a gaggle of caped and transplanted Carpathian neck noshers, now residing in South America and sucking on the maidenly necks of the local senoritas. And as it turns out, you would be incorrect pretty much all the way down the line, as the book is anything but simply written, and the vampires of its title are rather … well, more on them in a moment.

Just as it’s patently obvious that “You can’t judge a book by its cover,” it seems to me that one might justifiably add the statement “You can’t judge a book by its title, either.” Case in point: the novel that I recently experienced, Vampires of the Andes. Now, with a title like that, one might automatically be led to assume that this would be a rather pulpy, empty-headed affair; a simply written story, perhaps concerning a gaggle of caped and transplanted Carpathian neck noshers, now residing in South America and sucking on the maidenly necks of the local senoritas. And as it turns out, you would be incorrect pretty much all the way down the line, as the book is anything but simply written, and the vampires of its title are rather … well, more on them in a moment.

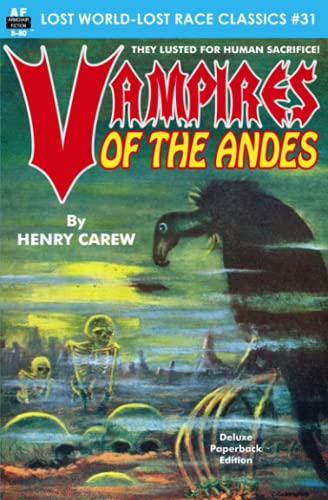

Vampires of the Andes was originally released as a 320-page hardcover book by the British publisher Jarrods, in 1925, and bearing the title The Vampire of the Andes on its beautifully faithful cover. The book would then go OOPs (out of prints) for a good 53 years, until Arno Press reprinted it in 1978 as part of its Lost Race and Adult Fantasy Fiction series, its title now changed, for some obscure reason, to The Vampires of the Andes. Flash forward another 35 years, to 2013, and the imprint Literary Licensing has released its own iteration of the novel, and with the title changed once again, to Vampires of the Andes. And most recently, in the fall of 2021, Armchair Fiction came out with its own edition, book #31 in its ongoing Lost World/Lost Race series, bearing the same title as on the 2013 edition, as well as some garish cover artwork that is not at all faithful to the story within. And I may as well say right here that these manifold title changes are probably the least mystifying element of this extraordinarily challenging book.

As to this novel’s creator, his name was Henry Carew, an Englishman about whom no biographical information is available today whatsoever, not even from the usually reliable Science Fiction Encyclopedia (in print and online) or the Internet Speculative Fiction Database. All that we seem to know is that Vampires of the Andes (I will go with that title, since it is the Armchair edition that I recently experienced) was Carew’s second and final novel, his first being another lost-race affair, 1923’s The Secret of the Sphinx, a book that has never been reprinted in the nearly 100 years since its release!

OK, now for the moment that I’ve been dreading. It’s about at this point in my book reviews here that I like to give prospective readers some kind of plot synopsis, so that they will know what the book is about, and I despair of doing so effectively in this case. You see, this novel is so very complexly plotted that I don’t even know where to begin. Wish me luck: The book, in a nutshell, concerns a worldwide secret organization, the Sacred Society of the Ankh, whose members are comprised of the various pure-blooded strains of the ancient Atlantideans … yes, from the legendary continent of Atlantis! As the reader gradually and painstakingly learns by piecing together bits of widely scattered information (far from being spoilers here, I think this bit of foreknowledge might actually abet the reader in his/her plumbing of this book), every 1,000 years, members of this secret group convene in an underground location to witness the resurrection of their seven ancient gods, who are brought back to life via chemical means and, before they return to their rest for another millennium, give their followers words of their celestial wisdom. Part of this sacred ceremony entails the sacrifice of seven virginal women, all of whom must bear the birthmark of the group’s totem, the legendary ara bird, on her arm. The reader is soon made acquainted with a large cast of characters, among them Quitu, a young Peruvian woman with the ara sign on her arm, who was given, shortly after her birth, to a kindly couple, the Della Priegos, to be cared for for life; Will Wootton, an English archeologist who is engaged to Quitu, and whose discovery of a mysterious, inscribed block, in the Peruvian ruins known as Chan Chan, and his removal of the block therefrom, set off the labyrinthine chain of events in this book; Professor Humphrey Stevenson, Will’s 60-year-old archeology teacher and mentor back in England, who receives the mysterious block from Will in the mail, endeavors to translate its multilingual inscriptions, and then sails to the Matto Grosso region of Brazil to help Will out; Henriquez Garcilasso, by day the editor of one of Lima’s major daily newspapers, and by night one of the Masters in the secret society; Juan Huarco, one of the subeditors on the paper and a lesser member in that same society, who is trying to get personal possession of the block for his own greedy purposes; and Father Antonio Bartholome, a priest in name only, who delights in his affairs with – and blackmailings of – any number of women in the Lima area, whose corruption is seemingly boundless, and who also wishes to lay his hands on that sacred block, despite not even knowing what the darn thing is.

Anyway, those are our dramatis personae, although Carew does manage to throw dozens of lesser characters into the mix, as well. Ultimately, Will, in his quest to find the mysteriously kidnapped Quitu, discovers that the Atlantideans are not only about to hold their millennial conclave, but that they also occupy the subterranean realm that exists beneath a goodly chunk of the top half of South America, replete with futuristic cities (including Aztlan, the mythical birthplace of the Aztecs) and a rapid-speed rail transit system! But even after Wootton is accepted into the lost Incan branch of the society, and has partaken of the Elixir of Life to attain a fellow life span of 800 years (!), can he possibly save Quitu from the fate that she has seemingly been born to fulfill?

Anyway, those are our dramatis personae, although Carew does manage to throw dozens of lesser characters into the mix, as well. Ultimately, Will, in his quest to find the mysteriously kidnapped Quitu, discovers that the Atlantideans are not only about to hold their millennial conclave, but that they also occupy the subterranean realm that exists beneath a goodly chunk of the top half of South America, replete with futuristic cities (including Aztlan, the mythical birthplace of the Aztecs) and a rapid-speed rail transit system! But even after Wootton is accepted into the lost Incan branch of the society, and has partaken of the Elixir of Life to attain a fellow life span of 800 years (!), can he possibly save Quitu from the fate that she has seemingly been born to fulfill?

Hmm, that summary wasn’t as difficult as I’d feared, but then again, you have no idea how much I’ve just simplified things for you here! Vampires of the Andes, to put it mildly, is not an easy read, for many reasons, and I must confess that at some points it was an outright challenge. As you may have discerned, Carew presents his readers with four separate groups of people who are plotting and counterplotting against one another. To make things even more problematic, several of the book’s main and subsidiary characters adopt aliases and disguises to further their shenanigans, and the author’s story line keeps shifting backward and forward in time. Concrete facts are dribbled out piecemeal, and for every bit of information we learn, a fresh conundrum arises to take its place. Remarkably, rather than clarifying itself as it proceeds, Carew’s plot grows increasingly byzantine practically all the way to the finish line! This is assuredly not the kind of book that allows for rapid-fire page turning, and I repeatedly had to go back and scan sections over again to keep things straight. Actually, I have a feeling that a repeat reading of Carew’s entire novel might be the best way to gain a proper appreciation for all the book’s myriad subtleties. As it was, I often felt that I was keeping up only by the proverbial skin of my teeth. To be succinct, Carew’s plot here is ridiculously complex, probably more so than is good for his book; this might thus be The Big Sleep of lost-race novels! No wonder poor Prof. Stevenson, at one point, declares “This seems pretty complicated,” and a friend of the Della Priegos is heard to exclaim “Why man, it bewilders me”!

And adding even more to the challenge of keeping up here is the superabundant wealth of historical, archeological and geographical detail that the author throws into his tale to give his fantasy plot a patina of verisimilitude. I don’t know if Carew ever visited Peru or not (as I said, virtually nothing is known of the man’s life), but if not, what a remarkable bit of research he evidently engaged in! Thus, the convincing descriptions of bustling Lima, including mentions by name of various streets, parks and plazas; a similar treatment for the former Incan city of Cuzco; and travelogue-type tours of Chan Chan and the Tiahuanaco ruins near Lake Titicaca. Never heard of Manco Ccapac, the Simorg, the Ara Vukub Cakix, the Taaroa, Viracocha, orichalc, Ukru, Byblos, the Rmoahals, the Turanians or the Akkadians before? You will have, by the time you finish Carew’s book. In it, the author seemingly delights in giving us mythological lore of a good dozen peoples, and for those readers with the patience to research all these many bits (yeah, that’s me), a very educational time can be had … again, at the expense of a page-turning reading experience. So Carew’s novel, ultimately, is an impressive, challenging and, as will be seen, somewhat frustrating one, all combined.

I am compelled to add that even the numerous praiseworthy facets of Carew’s book come freighted with their own problems. For example, one of the book’s most suspenseful sequences finds Stevenson sharing a luxury yacht with a party of the Atlantideans bound for South America; it’s just a shame that a wholly unlikely coincidence is responsible for the absentminded professor blundering onto the wrong boat to begin with! And sadly, Stevenson, perhaps the most well-drawn character in the book, disappears from the story around the 2/3 mark, never to be seen or heard from again; similar to the Della Priegos themselves. In another wonderful sequence, we see how one of Bartholome’s victims, Mercedes, frees herself from the evil priest’s clutches, and then, sadly, she disappears from the story as well, barring a brief coda toward the end. In the book’s most harrowing action sequence, Wootton journeys for many days underground, encountering deadly snakes and a fiery chasm, and ultimately, in a mind-out-of-body experience, is vouchsafed a glimpse of the history of man’s evolution. But sadly again, Carew’s descriptive powers here are not fully up to the task. Similarly, his descriptions of the futuristic cities underground, and the forests (?!) that surround them and the rail system connecting them, are all somewhat vague and nebulous. Carew, to be fair, does write impressively for the most part, although he is not above the occasional grammatical gaffe; he repeatedly writes something like “He decided to try and climb” rather than “to climb,” for example. Carew manages to keep a tight grasp on his story’s mazelike details, but even he manages to get confused at times, such as when we hear that Atlantidean Lord Kritchenham, the owner of that luxury yacht, is supposed to pick up a party of his fellow European brethren at Brest (page 22), although, around 120 pages later, we find all those Europeans already aboard, long before the yacht stops in France. And even though Incan expert Wootton tells us that Huayna Ccapac was the last reigning Inca, as far as I can tell, it was a personage named Atahualpa. But what do I know? I’m as much an Incan authority as the next person!

And, oh … another source of frustration mixed in with the good here occurs when we are given instructions and ingredients for making the Elixir of Life! Thus, we learn of the necessary tortoise egg albumen, the fumes of pulverized diamonds, the various animal protoplasms, the helium, radium and lead, the brain centers of various furry animals … but not nearly quite enough information to make our own Elixir at home! Well, alright, maybe this was intentional on Carew’s part. To get serious again, though, during the reawakened gods’ seven messages to their people (a scene that is strangely something of an anticlimax), we hear over and over again a similar refrain:

…Man must abandon the course he is pursuing and be content with what he may yet learn from the Tree of Knowledge. Light is not reached by seeking the unattainable, but by following the dictates of the pure soul God gave us…

Too bad that this laudable message is undercut by the necessity of those virginal sacrifices, the unfortunate seven maidens being exsanguinated by the legendary ara birds (the actual “Vampires” of the title, one must assume; who the singular “Vampire” of the book’s original title may have been, I haven’t a clue). Anyway, as you can tell, Vampires of the Andes really is something of a mixed bag, albeit an impressive one. It was with a sigh of relief that I crossed the finish line with this one, and if some fine, enterprising publisher (such as Armchair) were to decide to finally reprint Carew’s The Secret of the Sphinx next year, on the occasion of its centennial, I would have to think long and hard about whether or not I’d want to tackle this author again. Good as it was, Vampires of the Andes was almost too much for me…

I don’t know about the book, Sandy, but this is quite a review!

Hopefully, easier to comprehend, at least! 😂

Found a copy of ‘Secret of the Sphinx’ and was trying to research the book, then the author. This review turned up early and I am somehow more and yet less keen to read it based on Carew’s other book!

Go for it, Lottie, and then let us know what you thought. I’d be curious….

Hoo boy, I’m finding this book quite a slog…even after 200 pages, though it finally started to pick and become more coherent with the yacht episode. Carew’s writing style is fast and loose, in the sense that he seems to breathlessly write the story, making it up as he goes along, and does little if any editing or revising. I’d hazard a guess that this is someone used writing to a deadline for a penny a word, and that he wrote for pulps under a different name. It’s just soooo convoluted — the pacing, the characters, the plot, the writing. A more skilled writer could edit it down to a really enjoyable novel if half the size.

One bibliographic note: I’m holding in my hands the 1925 Jerrold’s edition and it most definitely is called The Vampires [plural] of the Andes. I got curious and saw that many online sellers list it as “Vampire” but their own photo of the book says “Vampires.” Digging deeper, it seems the confusion lies in the original dust jacket which uses the singular—- and must be a misprint. https://www.dustjackets.com/advSearchResults.php?authorField=Henry+Carew&action=search

Two hundred pages in…you can do it, Chico! It would be a shame to give up now!