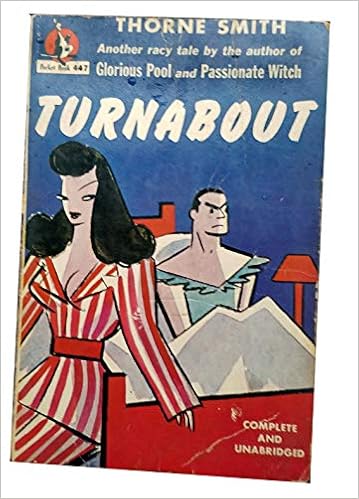

![]() Turnabout by Thorne Smith

Turnabout by Thorne Smith

It has been a good number of years since I last read Thorne Smith’s ribald fantasy classic entitled The Night Life of the Gods (1931), but I can still recall how thoroughly enjoyable and hilarious the book was for me. In this wonderful romp, a NYC-based scientist, Hunter Hawk, invents a device that can turn people to stone. He soon meets Megaera, one of the Little People, who has the converse ability to turn statues into living people, and the two later manage to bring all the stone effigies of the ancient Roman gods at the Metropolitan Museum to life, with increasingly madcap results. The book was chosen for inclusion in Cawthorn & Moorcock’s excellent overview volume Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, and deservedly so. But Night Life… was not the only ribald and uproarious fantasy written by Thorne Smith in 1931 to attain pride of place in Cawthorn & Moorcock’s volume. That same year, in the depths of the Great Depression and the Prohibition Era, Thorne gave to the world not only his first (and only) children’s book, Lazy Bear Lane, but also the great adult fantasy Turnabout, which Cawthorn & Moorcock describe using such words as “outrageous,” “fantastic” and “light-hearted.” Personally, I just loved it!

It has been a good number of years since I last read Thorne Smith’s ribald fantasy classic entitled The Night Life of the Gods (1931), but I can still recall how thoroughly enjoyable and hilarious the book was for me. In this wonderful romp, a NYC-based scientist, Hunter Hawk, invents a device that can turn people to stone. He soon meets Megaera, one of the Little People, who has the converse ability to turn statues into living people, and the two later manage to bring all the stone effigies of the ancient Roman gods at the Metropolitan Museum to life, with increasingly madcap results. The book was chosen for inclusion in Cawthorn & Moorcock’s excellent overview volume Fantasy: The 100 Best Books, and deservedly so. But Night Life… was not the only ribald and uproarious fantasy written by Thorne Smith in 1931 to attain pride of place in Cawthorn & Moorcock’s volume. That same year, in the depths of the Great Depression and the Prohibition Era, Thorne gave to the world not only his first (and only) children’s book, Lazy Bear Lane, but also the great adult fantasy Turnabout, which Cawthorn & Moorcock describe using such words as “outrageous,” “fantastic” and “light-hearted.” Personally, I just loved it!

Turnabout was initially released as a $2 Doubleday hardcover, its front cover sporting the somewhat misleading blurb “A hilarious comedy of modern morals and manners.” Almost a dozen other editions would follow, not counting various e-book incarnations. The volume that I was fortunate enough to acquire is the 1940 movie tie-in hardcover from Sun Dial Press, its dust jacket picturing the film’s stars Carole Landis and John Hubbard. (I know, I know … John WHO?) Now, as to Thorne Smith himself, for those of you who have not had the pleasure of encountering him as of yet, he was born in Annapolis, Maryland in 1892, the son of a naval commodore. After working in an advertising agency for some time, Smith entered in on his career as a novelist, and before his premature passing in 1934, at age 42, managed to come out with some 13 novels, plus a book of poetry, a book of short stories based on his own time in the Navy, and that children’s book. His 1926 classic Topper was famously filmed in 1937, and its sequel, 1932’s Topper Takes a Trip, made it to the big screen in 1939. His final book, a posthumous affair entitled The Passionate Witch (1941), would appear in theaters the following year under the title I Married a Witch and helped jump-start the career of Veronica Lake; it would also serve as one of the inspirations for the classic ‘60s TV show Bewitched. As for Turnabout, besides providing the source material for that 1940 film, it is also the basis for the short-lived television comedy in 1979 that lasted all of seven episodes, and gives us a plot device that has since become a classic in and of itself. More on this in a moment.

Turnabout introduces the reader to the not-so-happily married couple Tim (age 35) and Sally (age 28) Willows, who have been wedded for all of five years. The hard-drinking Willowses live in the pleasant suburban community of Cliffside (whether or not this is supposed to be the town of Cliffside Park in NJ is never made clear) with their two servants, the Twills, and their gigantic, cravenly and imbecilic dog, the appropriately named Dopey. When we first encounter Tim and Sally, they are engaged in what is seemingly their favorite pastime … arguing endlessly about the most trivial of subjects, in this case the manner in which Mr. Willows removes his socks at night. A wild party later that evening in their house leads to the inevitable sexual hanky-panky amongst their guests, including local lothario Carl Bentley putting the moves on Sally herself, resulting in his near murder by Tim with a rolling pin. The next day, Tim and Sally are at it again, each complaining about the other’s more fortunate lot. Tim is jealous of Sally being able to stay at home all day while he commutes to his miserable copywriter job at a NYC ad agency, while Sally has already opined “I wish I could change places with you. Oh, how I do! You clear out of it all every morning, go to the city and see something new – eat where you like and what you like – interesting men to talk to – good-looking girls to see … I’d change places with you quick as a wink. [I’m a] prisoner. All I need is a striped suit and a number…” But unbeknownst to the bickering Willowses, their conversation is being overheard by a very unlikely and increasingly annoyed auditor: Mr. Ram, an ancient Egyptian statuette that had been given to Tim by his globe-trotting Uncle Dick. And eventually, Mr. Ram has had enough, and using his/its mystical arts, takes some decided action.

Thus, the following morning, Tim is aghast to find himself – or rather, his soul/spirit/essence – residing in Sally’s body, and his wife’s spirit residing in his! Mr. Ram, it seems, has effected some kind of turnabout switcheroo to teach the couple a well-needed lesson! After some understandable stupefaction, Sally does what she has to do: namely, put on Tim’s suit and hop on the commuter train to go to work. And Tim, in Sally’s lovely form, but with a cigar firmly clamped between his teeth, heads to the dressing room to figure out the intricacies of donning makeup, a brassiere and garters. (Interestingly, when “Tim” is referred to in the book, the author means the man trapped in a woman’s body, and the same for “Sally.” We get the sense that the author is telling us that a person is what his/her spirit or essence is, and not the fleshly shell that it inhabits.) As the book progresses, we see how each of the two fares, with Sally having increasingly wacky adventures at the office (almost creating a scandal when she thoughtlessly walks into the ladies’ room) and Tim finding it more and more problematic to fend off the advances of that lustful Carl Bentley. No wonder the 1980 Del Rey/Ballantine edition of Turnabout (the last English-language print edition to date) gave customers the blurb “The other person’s grass is always greener … until you have to mow it”! And then, just as matters are beginning to settle down just a little bit, Tim comes to realize, to his panic-stricken disbelief, that he is very much pregnant…

In my review of the superior horror film The Mephisto Waltz (1971), I mentioned that I have long been a fan of these mind/body swap stories – even the widely reviled final episode of Star Trek, whose title, “Turnabout Intruder,” is a seeming homage to Thorne’s classic work – and this 1931 granddaddy of the genre is surely no exception. (And no, I still haven’t seen the popular hit of 2003 entitled Freaky Friday.) As Cawthorn & Moorcock mention, in this book “the incidents become progressively more outrageous.” And indeed, despite the fact that Turnabout is very episodic in nature, the author yet manages to pile up one marvelous comedic set piece after another. The book thus features any number of terrifically amusing scenes, including that drunken cocktail party; the sight of the ineptly made-up Tim entertaining the visiting gossip Mrs. Jennings; a church supper that the drunken Tim and Sally manage to bring to mayhem; Tim’s first visit to an obstetrician; the extended segment in which Sally has to entertain a visiting client, with the two ultimately falling asleep, in a drunken (there’s that word again!) stupor, in a parked ambulance, and later being tormented inside a morgue and a madhouse; the wild vengeance that Tim exacts on the lecherous Bentley; a madcap sequence in a police station and a courthouse; and, of course, Tim’s hysterical (in both senses of the word) delivery in a put-upon hospital. (The book is perfect fare for all those people who have ever wondered how a man might deal with the travails of pregnancy and parturition!) And the book, as I say, is funny; laugh-out-loud funny, and I am not a person who laughs out loud very often while reading. Actually, Turnabout may just be the funniest book I’ve read since Eric Frank Russell’s The Great Explosion (1962) around five years ago.

What makes Smith’s book so very amusing? I hesitate to go into it, as any discussion of what makes something funny almost inevitably tends to rob it of the magical quality that makes a person laugh in the first place. But let’s take a chance here. Part of what makes Smith’s work so funny here are some of the characters’ names, such as Dopey, naturally, but also Tim’s boss, Mr. Gibber, who delivers a protracted speech on the necessity of brevity. The author is not above the use of puns in his work (when Tim asks Sally if she expects him to whelp their young single-handed, she replies “God helps those who whelp themselves”), as well as constant put-downs and insults (“You’d be writing poison-pen letters if you knew how to write,” Tim tells a female neighbor). The fact that Tim and Sally are swizzled much of the time is funny (the removal of his booze while pregnant is especially tough on Tim), and the fact that people in an argument often get sidetracked by insignificant words is especially so. Thus, Mr. Gibber, when exhorting his underlings to be more pithy, gets into a whole big thing with Tim when Tim asks “You mean the stuff that goes into helmets?” The book’s many wry comments are funny (such as when Tim thinks “People who waited for breaks … usually went broke,” and when Sally muses “Men and women were merely animals that put their fur coats in storage or pawn instead of shedding them all over laps and landscapes”), and imaginative and crazy situations abound. The screwball comedy was a distinct cinematic genre of the 1930s, and Turnabout might fairly be termed a screwball novel. Unfortunately, the 1940 film, which I once saw at NYC’s Film Forum, double billed with another Carole Landis picture, One Million B.C. (also from 1940), is, if memory serves, nowhere near as funny, and that 1979 TV show, from what I’ve heard, was pretty dreadful. Comedy, it would seem, is a very elusive proposition, unless all the ingredients are under the firm control of a master, as they are here.

What makes Smith’s book so very amusing? I hesitate to go into it, as any discussion of what makes something funny almost inevitably tends to rob it of the magical quality that makes a person laugh in the first place. But let’s take a chance here. Part of what makes Smith’s work so funny here are some of the characters’ names, such as Dopey, naturally, but also Tim’s boss, Mr. Gibber, who delivers a protracted speech on the necessity of brevity. The author is not above the use of puns in his work (when Tim asks Sally if she expects him to whelp their young single-handed, she replies “God helps those who whelp themselves”), as well as constant put-downs and insults (“You’d be writing poison-pen letters if you knew how to write,” Tim tells a female neighbor). The fact that Tim and Sally are swizzled much of the time is funny (the removal of his booze while pregnant is especially tough on Tim), and the fact that people in an argument often get sidetracked by insignificant words is especially so. Thus, Mr. Gibber, when exhorting his underlings to be more pithy, gets into a whole big thing with Tim when Tim asks “You mean the stuff that goes into helmets?” The book’s many wry comments are funny (such as when Tim thinks “People who waited for breaks … usually went broke,” and when Sally muses “Men and women were merely animals that put their fur coats in storage or pawn instead of shedding them all over laps and landscapes”), and imaginative and crazy situations abound. The screwball comedy was a distinct cinematic genre of the 1930s, and Turnabout might fairly be termed a screwball novel. Unfortunately, the 1940 film, which I once saw at NYC’s Film Forum, double billed with another Carole Landis picture, One Million B.C. (also from 1940), is, if memory serves, nowhere near as funny, and that 1979 TV show, from what I’ve heard, was pretty dreadful. Comedy, it would seem, is a very elusive proposition, unless all the ingredients are under the firm control of a master, as they are here.

For the rest of it, Smith also has some points to raise in his otherwise comedic novel, and allows himself opportunity to make some trenchant comments on such subjects as suburban living, the world of advertising (a milieu that the author knew all too well), church suppers (based on his extensive comments, the reader gets the feeling that Smith must have suffered through any number of them!), and modern-day morality. And speaking of that latter, his book is surprisingly frank when it comes to sexual matters, and the swinging suburbanites we witness give the ‘60s free-love hippies a run for their money! Indeed, Tim drunkenly couples with the attractive divorcee Mrs. Meadows on the night of that drunken party, an infraction that Sally forgives quite readily. No wonder the 50-cent Paperback Library edition from 1963 called the book “Thorne Smith’s sexiest novel” on its cover (actually, I’ve heard from several sources that Smith’s 1933 work Rain in the Doorway is his most risqué novel), and the 60-cent Paperback Library edition from 1965 somewhat misleadingly proclaimed “A dazzling, sexy novel about wife and husband swappers.” The book holds up marvelously, more than 90 years after it first appeared.

Indeed, I have very few complaints to lodge against Thorne Smith’s work here. Yes, the resolution of the book may be even more far-fetched than its setup, but then again, who knows what the limits of Mr. Ram’s extraordinary powers may be? Some bits in the book are unavoidably dated (such as references to President Hoover, the Volstead Act, and the difficulty of understanding those newfangled “talkies”), but not nearly as many as one might expect. I also found it a bit odd that the author refrains from telling us the gender of the baby that Tim delivers, obfuscating matters by calling the kid “the bundle,” “the infant” and “the child.” Still, this was obviously a deliberate decision on the part of the author. The bottom line is that Turnabout is a splendid entertainment, surely deserving, after 42 years, of a new edition in print. Good laughs, after all, are something that all of us could use more of these days. As for me, I look forward to reading more of Thorne Smith in the near future. The hardcover entitled The Thorne Smith 3-Bagger, from 1934, which includes the comedic fantasies Topper, Skin and Bones (1933) and The Glorious Pool (1934) in one volume, is even now exerting its siren call on me…

Indeed, I have very few complaints to lodge against Thorne Smith’s work here. Yes, the resolution of the book may be even more far-fetched than its setup, but then again, who knows what the limits of Mr. Ram’s extraordinary powers may be? Some bits in the book are unavoidably dated (such as references to President Hoover, the Volstead Act, and the difficulty of understanding those newfangled “talkies”), but not nearly as many as one might expect. I also found it a bit odd that the author refrains from telling us the gender of the baby that Tim delivers, obfuscating matters by calling the kid “the bundle,” “the infant” and “the child.” Still, this was obviously a deliberate decision on the part of the author. The bottom line is that Turnabout is a splendid entertainment, surely deserving, after 42 years, of a new edition in print. Good laughs, after all, are something that all of us could use more of these days. As for me, I look forward to reading more of Thorne Smith in the near future. The hardcover entitled The Thorne Smith 3-Bagger, from 1934, which includes the comedic fantasies Topper, Skin and Bones (1933) and The Glorious Pool (1934) in one volume, is even now exerting its siren call on me…

The trope of “careful what you wish for” is one of my faves.

Yes, those wishes made in haste often DO tend to backfire, don’t they?

Seems like!