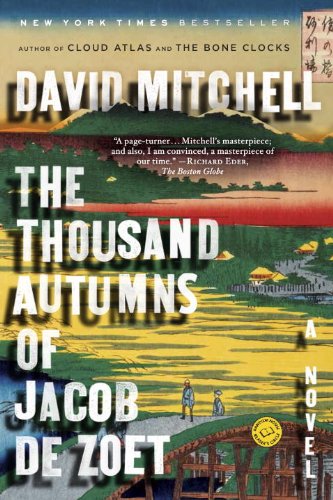

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet by David Mitchell

The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet by David Mitchell

Let’s just admit it at the outset. As someone who tries to write, I hate David Mitchell. Hate him with the white-hot intensity of a thousand blazing suns. It’d be bad enough if he were just a great, you know, writer. Plain old everyday writer of some kind of novel: literary fiction, sci-fi, adventure, pastiche, historical. But no. He can’t just pick one. He has to be brilliant at them all. In one novel, no less (Cloud Atlas, by the way, and if you haven’t read it yet, you should. Then fire off an angry letter to any award group that didn’t give him their top prize for it. Yeah — I’m talking to you Booker). Worse, Cloud Atlas wasn’t his first brilliant book. And then he followed it up with Black Swan Green. And now he’s back with The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet.

Well, I say “hah!” to you Mr. David Mitchell. Hah! Cuz The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet isn’t brilliant. It’s only kinda brilliant. So there. Double hah!

The title character is a young Dutchman who arrives on the tiny island of Dejima, sole gateway for the Dutch East India Company to 19th century Japan, a closed society. De Zoet is here to make his fortune as a clerk in order to return home and marry up to his intended, Anna. But things quickly go awry: the East India Company is having monetary problems, the Japanese are reluctant to give up more of their highly-desired copper; global politics (revolution, Napoleon, the increasing strength of the English, the new America, etc.) are threatening the Company’s monopoly in Japan as well as Japan’s desire to remain closed; De Zoet is tasked to root out corruption among his fellow workers, making him none too popular; and he manages to fall in love with a Japanese midwife — Orito.

The language is typical Mitchell. Whether it be simple descriptive phrases (a newborn described as a “boiled-pink despot” or daylight being “bruised” by an oncoming storm) or his usual preternatural ability to change voice as needed, shifting seamlessly among differing classes, cultures, nationalities, genders, ages, formal speech or dialect, even human or feline. Dutch or English, male or female, slave or noble, bureaucrat or samurai, prig or whoring drunk — it makes no difference, all are rendered naturally and individually.

The structure is less complex than we usually see from David Mitchell, the book much more linear than usual, though we do shift narrators among varying sections. More typical, Mitchell is working with several genres at once, or successively: romance, clash of cultures, international gamesmanship, adventure story (complete with masked samurai and a daring rescue attempt), and a few others. It makes for a heady mix of characters and plotting, and one of the best aspects of the novel is how it rarely goes where you expect it to, in terms of either plot or style (or even narrator).

Characterization is sharp and rich from the smallest character to the major ones. If De Zoet seems perhaps a bit distant to us, we feel nothing but compassion for Orito as well as the young Japanese translator who also loves her.

The turn of the century (18th to 19th) offers up rich potential for Mitchell to explore: clashes between cultures as the world begins to shrink, between tradition and progress, science and religion, religion and religion (Christianity is adamantly banned from Dejima), old and new economic and political systems, between old empires and rising empires.

David Mitchell also explores, subtly, various forms of enslavement: actual slavery (in one of the most moving narrative sections of the novel, a slave discusses his “mind-island” — the only place he is free as his mind is the only thing he truly owns), economic slavery, sexual slavery, subjugation of the weak by the powerful — either as nations or classes, the oppression of tradition, the imprisonment of birth.

And as one might expect with such a setting, communication and miscommunication is also a major theme throughout, as characters try to feel their way to mutual comprehensible expression, sometimes succeeding, often failing. There is a pattern running through the novel of conversations being broken up, dialogue lines interrupted throughout the conversation with descriptive lines: the play of cards, shots in a billiard game, a drummer’s beatings, as if Mitchell is highlighting the sheer difficulty of simple conversation even without all the cultural baggage.

By this point, you’re probably wondering why the book is only “kinda brilliant.” Well, pacing is sometimes an issue. The book starts off with a bang (actually a birth) that you won’t forget soon. The first section is a bit up and down as we’re thrown a large cast of characters relatively quickly. But after that first section, pace is never an issue: fast when it needs to be fast and slow when it needs to be slow.

All right, I admit, it’s a small complaint. One might even say petty. But I can honestly say that The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet is no Cloud Atlas. And yes, I know that since Cloud Atlas is on my list of top 10 books of the past 20 years, that isn’t so damning. Fine then. Curse you, David Mitchell. The Thousand Autumns of Jacob De Zoet isn’t the best book of the past decade, but it’s damn good and yeah, might even be a bit brilliant. Read it. And if you’re a wannabe writer, the We Hate David Mitchell Club meets the first Monday of every month — see you there.

~Bill Capossere

Having your reputation precede you isn’t always a good thing. I’d never picked up a David Mitchell novel before. His list of accolades is ridiculous: he was selected as one of Granta’s best young British novelists, has graced the Most Influential People lists, been nominated for Bookers, yada yada yada. All I’d really heard is that he is deliberately difficult, with Stephen King making the rather sassy assertion that Cloud Atlas was a literary stunt. And then I read The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, and, just like every other FanLit reviewer, I’ve been charmed.

Having your reputation precede you isn’t always a good thing. I’d never picked up a David Mitchell novel before. His list of accolades is ridiculous: he was selected as one of Granta’s best young British novelists, has graced the Most Influential People lists, been nominated for Bookers, yada yada yada. All I’d really heard is that he is deliberately difficult, with Stephen King making the rather sassy assertion that Cloud Atlas was a literary stunt. And then I read The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet, and, just like every other FanLit reviewer, I’ve been charmed.

So, from what I’ve read, it appears that The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet follows a relatively vanilla structure compared to Mitchell’s other works. Most of the book follows Jacob de Zoet, a lowly clerk with the Dutch East Indies Company, in third person — with occasional leaps into first, and alternate character viewpoints. The story is also more or less chronological. The Dutch East Indies Company has arrived in Dejima, a small man-made island in the bay of Nagasaki, Japan. It’s populated by scheming traders, cutthroats, spies and double-crossers, which makes for a lovely backdrop for poor wide-eyed Jacob, who is only trying to save some money before returning to Holland in a few years to marry his beloved Anna.

At the kernel of the novel is a love story, which was definitely the most engaging of the many plots running through the book. Jacob falls for Japanese midwife Orito, and is swiftly warned off by Marinus, the doctor Orito is studying under. Thus begins Jacob’s first moral dilemma, torn between his loyalty for Anna and his growing infatuation with Orito.

Jacob’s integrity is a topic revisited again and again. “What de Zoet of Domburg, thinks Jacob, ever prostituted his conscience?” His morality must remain steadfast when everyone around him is festering in corruption. His honest accounting gets him into trouble with his seniors, who are siphoning money outright from the Dutch East Indies Company. His character arc is definitely the most satisfying in the novel. Mitchell attempts to add depth to minor characters by having them spout long monologues about their pasts out of the blue, but watching Jacob’s slow development from doe-eyed Pastor’s boy to an honourable leader is much more convincing.

The novel leapfrogs genres. It has elements of romance, historical and speculative fiction, hints of magical realism. When Orito is abducted, it turns into a rollicking adventure story (and this is where the elements of magical realism come into play). This frenetic jumping between plotlines and characters does get exhausting after a while, and I can begin to imagine what prompted King to accuse Mitchell of carrying out a ‘literary stunt.’ I almost gave up the novel because it was so inaccessible at first. The style is dense and difficult, and what is with Mitchell’s constant interrupting of dialogue!? Let me illustrate:

“I’ll keep yer breakfast,” Grote chops off the pheasant’s feet, “good an’ safe.”

“Here boy!” whispers Oost to an invisible dog. “Sit, boy! Up, boy!”

“Just a sip o’ coffee,” Baert proffers the bowl, “to fortify yer, like?”

“I don’t think I’d care,” Jacob stands up to go, “for its adulterants.”

The style is infuriatingly jarring at first, but there comes a nice rhythm to it after a while. And you have to hand it to Mitchell, the man can write. It’s one of those books that will have you jotting down quotes to remember. I’d be hard pushed to pick a favourite, but I think opening your novel with “A cacophony of frogs detonates” pretty much says it all.

The novel is dense. It’s complex. Where one book could only hope to tackle a single topic such as mortality or faith versus science or cross-cultural relations or the pivotal flaws of humanity, The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet deals with them all. It’s not an easy book, but the rewards are worth it.

~Rachael McKenzie

Great review; I’ll have to check this out. I’ve read Cloud Atlas (not a stunt) and Bone Clocks, but haven’t delved into his earlier stuff. I find Mitchell to be one of the most engaging writers I’ve ever read, which it sounds like is a quality he’s developed over time, i.e. I wouldn’t call Cloud Atlas or Bone Clocks “dense” because they’re never hard to get through. He doesn’t write propulsively; he just writes so that you’re interested in what he’s saying and what’s going to happen next. It does, though, sound like I need to put his while oeuvre on my reading list.

I haven’t read this one, but I loved BLACK SWAN GREEN.

The only thing holding me back from reading this is that I don’t know how to pronounce any of the Dutch names, so I’d be stumbling over them on every page. :(

Nice review–I loved this one by him. And I’d ignore King’s complaint and pick up Cloud Atlas.

Because even if it is a “stunt” (I don’t accept the premise that it is), who cares if the stunt is absolutely nailed and fully awesome? Seems a pretty stupid comment from a normally pretty smart guy.

Outside my usual reading range but sounds intriguing. Especially interested in the Dejima setting during the Sakoku period when the rest of Japan was closed to the outside world. Might want to read Cloud Atlas firth though.